After Tense Hearing, Oregon Poised To Join National Popular Vote Movement

READ ON

For the first time, a proposal that Oregon honor the national popular vote in presidential contests got a vote on the Senate floor on Tuesday, passing easily.

With the 17-12 vote, Senate Bill 870 moves on to the House of Representatives, where similar proposals have passed four times since 2007.

The decision means Oregon might well become the latest state to join the National Popular Vote Compact, an agreement among states to apportion their electoral votes not to whichever presidential candidate wins their own state, but to the candidate with the most votes nationwide.

The compact would kick in once there’s a critical mass of states involved, representing at least the 270 votes required to win the presidency. To date, 15 states have joined, totaling 189 electoral votes. Oregon would add seven votes to that total.

Debate over the bill was among the most robust that’s occurred in the Senate this year, with lawmakers in both parties speaking for and against the proposal.

Proponents argued honoring the national popular vote will ensure candidates focus on more than a handful of battleground states, and that it will ensure that, for instance, Republicans in reliably blue Oregon can influence a presidential contest.

“It doesn’t matter if I’m a Democrat or a Republican, in a blue state or a red state,” said state Sen. Michael Dembrow, D-Portland, a chief sponsor of the bill. “I have as much of a chance of influencing the election as someone in any state in the country. This is what ‘one person, one vote’ is all about, colleagues. It’s the fruition of what it means to be an American.”

Sen. James Manning Jr., D-Eugene, was among a number of senators who suggested the Electoral College is a relic. He likened the institution to the old phone booths built into the Capitol hallways, recalling an incident when he asked two young visitors if they knew what the booths were.

“They said, ‘We know. It’s an iPhone charging station,’” Manning said. “We have evolved as a country. It’s no longer a phone booth. It’s an iPhone charging station.”

Sen. Shemia Fagan, D-Portland, noted that two of three presidents since she’s been of voting age had been elected while losing the popular vote. President George W. Bush won in 2000 without achieving the most nationwide votes, and President Donald Trump trailed in the popular vote in 2016.

Those arguing against the idea included state Sen. Betsy Johnson, D-Scappoose, who joined two others in her party in insisting that voters should decide whether or not to join the popular vote compact.

“If we’re going to change how we elect the president of the United States, it should be referred to voters,” she said. “One Oregonian, one vote.”

Sen. Alan Olsen, R-Canby, suggested honoring the popular vote would give outsize influence to more liberal states and large cities. He said the Electoral College helps give conservative candidates a chance on the national stage.

“If we get to the national popular vote, I don’t ever see a Republican president … in the future,” he said.

He went on to say rural Oregonians “have been disenfranchised for many, many years. Our votes never count. Portland holds the day, every day.”

The session nearly took a combative turn after Sen. Lew Frederick, D-Portland, spoke of the history of the Electoral College. One of its early provisions was that three-fifths of slaves in slave states would be counted to determine the states’ number of representatives in the House of Representatives.

“Let’s remember that under the Electoral College, the initial system, I would be considered three-fifths of a person,” said Frederick, who is Black. “One of the reasons we had [the Electoral College] was to try to deal with the free and the slave states.”

Frederick went on to describe a legacy based on that calculus that he said contributes to disenfranchisement of minorities in the present day.

But the comment prompted a retort from Sen. Dennis Linthicum, R-Klamath Falls, who is white. Linthicum said the “three-fifths compromise” was merely a way to ensure slave states didn’t have outsized representation.

“It was not because anybody ever believed — or maybe there were people who did believe, but it’s not in the form of the nation — that three-fifths was an appropriate measure of a man,” Linthicum said. “That the impact of the slave states was lessened because of the three-fifths attribution to representation is an important concept to understand. Slavery was destined to die, and it’s important that we recognize that. And I’m so glad it did. That’s why we have the ability to be equal men and women in the United States today.”

The comments caused a stir in the Senate chamber, prompting audible incredulity from Frederick. He was soon surrounded by Sen. Manning, who is Black, and Senate Majority Leader Ginny Burdick, D-Portland.

Several senators made reference to Linthicum’s comments, including Sen. Jackie Winters, R-Salem, who is also Black. Winters said she “would encourage each and every one of you to take and maybe look at the history lessons that got us here today.”

Frederick rose to respond, saying “the three-fifths issue is not a minor issue. It’s not just a historical reference. This is a reality for people around the country. It is a reality for my family across the country.”

Linthicum wound up having lengthy conversations with both Manning and Frederick on the issue. Afterward, he reiterated his opposition to slavery, and said he stood by his comments.

“Because of that incident where three-fifths got established, that actually stripped power out of the slave states, and I think that that was a good thing,” he said.

The spirited debate was fitting for the issue, which despite being introduced again and again over the years had never once gotten a hearing in the full Senate. That was because of Senate President Peter Courtney, D-Salem, who opposes any proposal to apportion Oregon’s electoral votes without approval from voters.

Courtney has taken heat for that position over the years — including an attempt to get him voted from office last year by national popular vote proponents. This year, he decided to allow a vote on the Senate floor after it was clear enough Democrats supported the bill for it to pass.

In the end, three Democrats voted against the bill: Courtney, Burdick and Johnson. Two Republicans supported it: Sen. Brian Boquist, R-Dallas, who was a chief sponsor, and Sen. Chuck Thomsen, R-Hood River.

The bill now moves onto the House of Representatives. Gov. Kate Brown’s office says she supports the proposal.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Congress Blocks Objections To Election Results, Delayed After Long Day Following Insurrection

The votes came after Congress reconvened hours after violent insurrectionists stormed the Capitol, forcing party leadership to evacuate the scene while rioters overtook the complex. Continue Reading Congress Blocks Objections To Election Results, Delayed After Long Day Following Insurrection

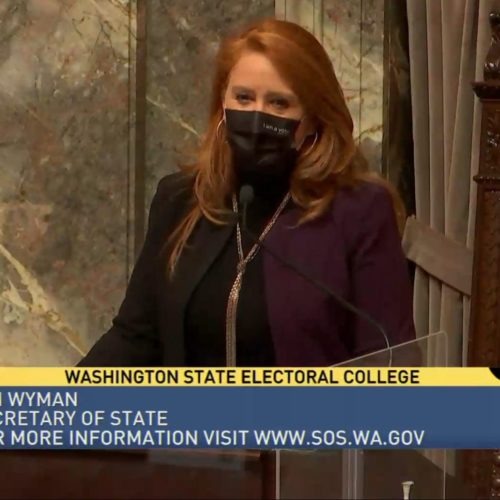

Washington’s Electoral College Meeting In Olympia Full Of Emotion And Gratitude

Electoral college delegates in all 50 states cast their ballots Monday. In Olympia, Washington’s 12 Democratic electors cast their ballots for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris. It was an emotional experience for some, including for person running the meeting. Continue Reading Washington’s Electoral College Meeting In Olympia Full Of Emotion And Gratitude

When Will We Know The Winner? Time Frames For Key States; AP Calls Michigan For Joe Biden

Here’s how much longer it will take to count the votes in the remaining key states of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina and Wisconsin. Continue Reading When Will We Know The Winner? Time Frames For Key States; AP Calls Michigan For Joe Biden