BOOK REVIEW: Saeed Jones’ Eloquent Coming-Of-Age Is Hard To Read — And Harder To Put Down

LISTEN

BY MAUREEN CORRIGAN

Editor’s note: This book review cites a passage containing a homophobic slur.

One could say that Saeed Jones’ new memoir, How We Fight for Our Lives, is a classic coming-of-age story. A boy grows up in Texas; he’s black, gay and isolated; he’s raised by a single mom; he struggles with identity, goes off to college and, eventually, achieves a wobbly sense of self-affirmation.

But Jones’ voice and sensibility are so distinct that he turns one of the oldest of literary genres inside out and upside down. Take his intricate reflection on an incident when he was 12, where two sort-of friends brutally turn and ostracize him with one word:

Author Saeed Jones

“You never forget your first ‘faggot’. Because the memory, in its way, makes you. It becomes a spine for the body of anxieties and insecurities that will follow, something to hang all that meat on. Before you were just scrawny; now you’re scrawny because you’re a faggot. Before you were just bookish; now you’re bookish because you’re a faggot.

Soon, bullies won’t even have to say the word. … There will already be a voice in your head whispering ‘faggot’ for them.”

How We Fight for Our Lives is at once explicitly raunchy, mean, nuanced, loving and melancholy. It’s sometimes hard to read and harder to put down. Jones’ memoir effectively deep-sixes any illusions I had that it must’ve been a little easier in recent decades to come of age as a queer black boy in Texas. Granted, Jones’ public high school is open-minded enough to host a touring production of The Laramie Project, the play about the hate-crime murder of Matthew Shepard; but what Jones takes away from that performance is that he’d better closet himself even more securely at school. Jones recalls his younger self realizing that, “Being a black gay boy is a death wish. And one day, if you’re lucky, your life and death will become some artist’s new ‘project.'”

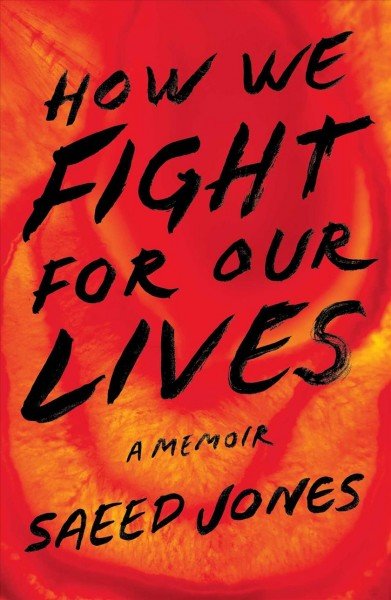

‘How We Fight for Our Lives:

A Memoir’ by Saeed Jones

Throughout How We Fight for Our Lives, readers feel the tension of Jones’ adolescent and college years, as he’s trying to figure out how to be. By the time he gets a full scholarship to Western Kentucky University for his debate skills, Jones is a roiling vessel of shame, need and anger. He’s explicit in his accounts of using sex to humiliate himself and his partners, especially the straight white men he seduces. Jones says:

I hungered for the power of the all-American man … If I couldn’t actually be … one myself, I thought I could survive by devouring him whole … If America was going to hate me for being black and gay, then I might as well make a weapon out of myself.

All this time, Jones’ mother remains a steady, loving presence in his life. She’s out of the apartment a lot when he’s growing up, working long hours at her job at the airport, but she always tries to be supportive — up to a point. She really doesn’t want to talk about Jones’ sexual identity. One evening, when he’s in college, Jones casts his eyes downward and starts a conversation with his mom about a guy he dated. Here’s how that goes:

When I looked up, she was staring at me, wide-eyed, almost pleadingly — as if I’d led someone afraid of heights to the edge of a rusting bridge. And then I did exactly what I thought all people who love each other do: I changed the subject; I changed myself; I erased everything I had just said; I erased myself so I could be her son again.

How We Fight for Our Lives is a raw and eloquent memoir. I don’t think I’m taking away from the particularity of Jones’ experience when I say that, in passages like the one above, Jones also speaks to how difficult it is for nearly everybody to hold onto to that vulnerable construction we call our “selves.” Jones reminds us that an Invisible Man, illuminated only with a bare bulb, is not only unseen by others — he is barely seen by himself.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))