Past As Prologue: How The Namesake Of Pullman Tried To Improve Worker’s Lives, But Failed

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

BY KAREN PHOENIX

Some industrialists in the late 1800s attempted to improve living conditions for their workers, though not successfully.

Old black and white photo of workman’s housing in Pullman, Illinois. CREDIT: Library of Congress/WikiCommons

Take George Pullman, the inventor of the railroad sleeping car. Fun fact: Pullman, Washington is named after him, though it’s not clear why. Pullman was concerned about the living conditions of his workers. So when he built his factory south of Chicago in the 1880s he also built a model town next to it.

The housing for his workers was spacious (by the standards of the day) and included the latest technology — indoor plumbing and sewers. There were stores, a church and a fancy hotel. The town was tightly controlled by Pullman, who did random inspections and fired people for drinking on their days off. But, hey, indoor plumbing, right?

Then came a nationwide economic downturn. In 1893, Pullman reduced wages by 30% but kept rent the same. Workers went on strike. Pullman refused to negotiate with the strikers and left town.

National Guardsman lined up during the Pullman Railcar strikes. Thirty-four people were killed in riots and sabotage caused $80 million in damages. CREDIT: Library of Congress/WikiCommons

President Grover Cleveland sent the National Guard. Troops fired on the strikers. Thirty-four people were killed, and the strike failed. Eight years later, the Supreme Court of Illinois forced Pullman to sell the town, and it was annexed by Chicago.

The strike—and the violence that occurred—became George Pullman’s legacy, rather than his attempt to create the utopian worker’s town. When he died, his family buried him in a lead-lined coffin because they were concerned workers would try to desecrate it.

There were many other bloody strikes during the Gilded Age, which impacted whole industries like the railroad or garment workers, and bloody strikes in mining camps and other factory towns. Communism and anarchism also grew during this time.

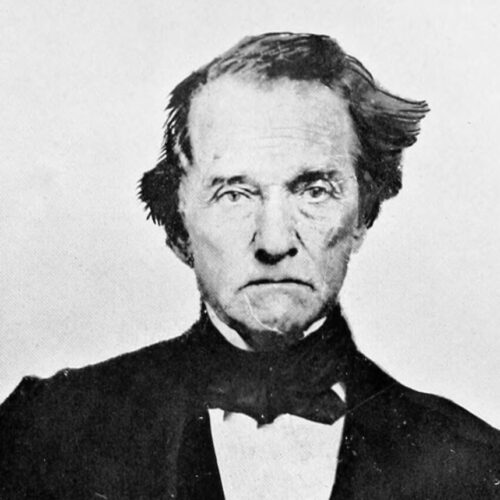

George Pullman had a net worth of $17.5 million at the time of his death. CREDIT: William Shaw Warren/Creative Commons

While there are a lot of differences between our situation today and the Gilded Age, there are important lessons for us, most especially that when large groups of people feel like they don’t have an opportunity to rise economically, or feel that there are fundamental failures in economic or governmental systems, they may try to overturn those systems in some way.

We’ve seen echoes of this, although not nearly to the degree or scale, in the Occupy Wall Street movement among many others today.

Related Stories:

Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

Past as Prologue essay about gendered epithets in Pacific Northwest politics and beyond. Continue Reading Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

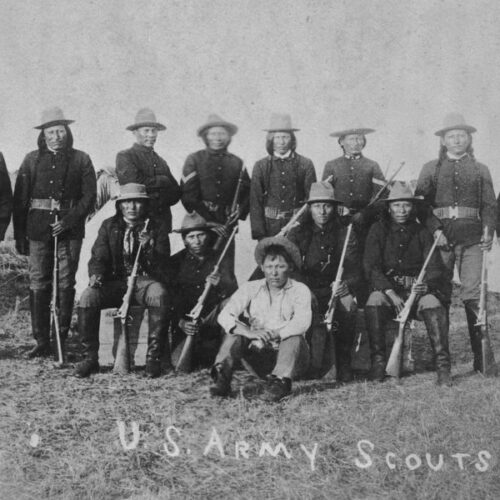

Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

The story of some Native American Scouts and their complicated reasons for working with the United States government. Continue Reading Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

In this Past as Prologue essay, WSU Professor Karen Phoenix explains the history of the shipping container and its Spokane ties. Continue Reading Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry