Bruce Lachney used to fly Boeing 737s for Delta Air Lines. But in 1988, he bought a farm outside of Eatonville, Washington. He began planting cranberries in the early 1990s.

Today, he and his wife, Ann Lachney, still run Rainier Mountain Cranberries. They sell their berries at farmers markets in Seattle and Mercer Island.

“Cranberries are the perfect American berry,” Bruce Lachney said. “They are an indigenous fruit. A lot of our berries have come from various sources overseas, various other countries, and have become hybrid berries. But cranberries are the unique berry of America.”

Tons of Northwest ingredients — like cranberries, turkeys and potatoes —can be found on your own Thanksgiving table.

Cran-tastic

Oregon and Washington states grow around 5,000 acres of cranberries every year.

Much of the Northwest cranberry harvest starts near the beginning of October. Most people associate cranberries with bogs, or flooded harvests.

But many cranberries are also harvested out of their beds dry with a machine called a Furford picker-pruner, which looks like an overgrown push lawnmower.

It picks the low-growing berries from their vines that are about 7 inches tall. The cranberries that are harvested dry can make better and more stable berries to sell to the fresh market, while many of the floated fruit becomes cranberry juice or puree, Lachney said. Cranberries represent a lot of things to many people, he said. But the pop of color on the Thanksgiving table is something he thinks most can appreciate.

“When you’re putting forth a meal for everyone, there’s a lot of browns and blacks and all kinds of other food that’s out there, but cranberries are that bright red,” Lachney said. “They give you that special season that you see. It’s a holiday of color.”

Cranberry farmers set their fruit one year ahead. That means farmers are harvesting one crop while managing next year’s.

“Cranberries are a very humbling crop,” Lachney said. “Because you’ll have a really good crop one year, and you think, ‘I’ve got it all figured out.’ And the next year, nature just comes down and slaps you down and says, ‘No, you don’t.’ That’s pretty much cranberry growing.”

Lachney said there are many variables that could take down cranberries: poor yields and color, bugs, weeds, fungus and frost.

Turkey Lurkey Time

Many of the nation’s commercial turkey farms are in California, the Midwest and the Mid-Atlantic. But the Northwest does have a handful of specialty turkey farms and butchering operations.

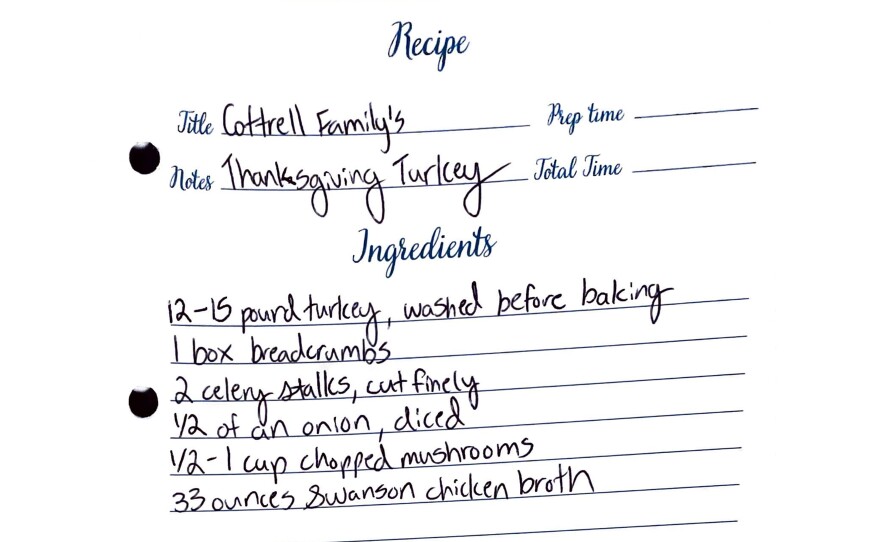

Nathan Cottrell is with Chick Chaser — a turkey and poultry farm and butchering operation out of Benton City, Washington.

He said his turkeys can sometimes be a pain, as they’re free-range birds. They often wander to the neighbors, and there’s the risk of dogs that might attack them. But Cottrell said there are good parts about raising turkeys, too.

“I think the highlight of it is when they start getting bigger and they start following you around. When you feed them, or when you go out and talk with them, they’ll talk back,” Cottrell said. “They’re little dogs, really. They’ll just follow you around.”

Cottrell said even after 15 years of raising birds, he still gets emotionally attached to them. He says after a 2015 bird flu incident wiped out all his family’s birds, he has been building his flock back slowly to more than 30 birds. The special breeding tom birds that will be spared — named Kawasaki, Blue and Nag — get marked with a special zip tie around their legs.

Cottrell said it’s a bit too late for Thanksgiving orders for this year. Most of his birds have long since sold.

“We occasionally get customers who drive by and say, ‘Hey can we get one?’” he said. “If people want them for next year, we can take orders for next year, make sure we have a bird ready for them.”

Spectacular spuds

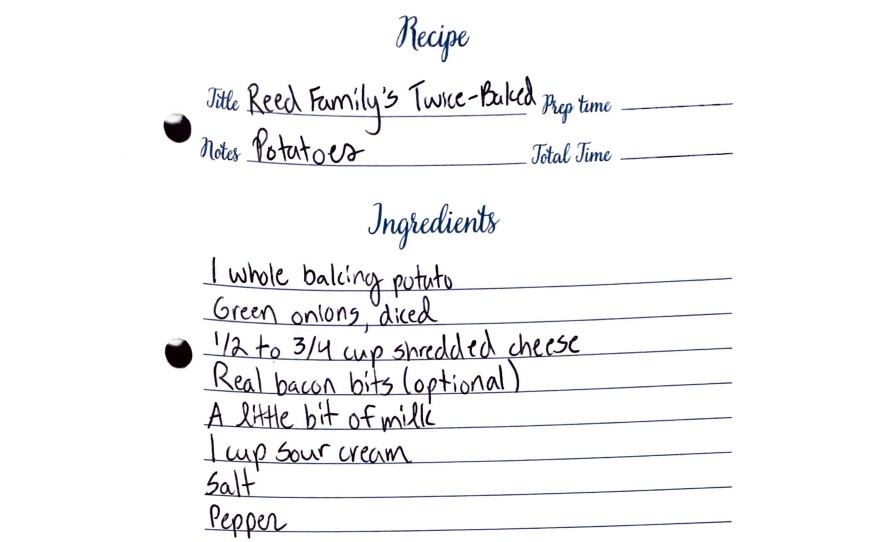

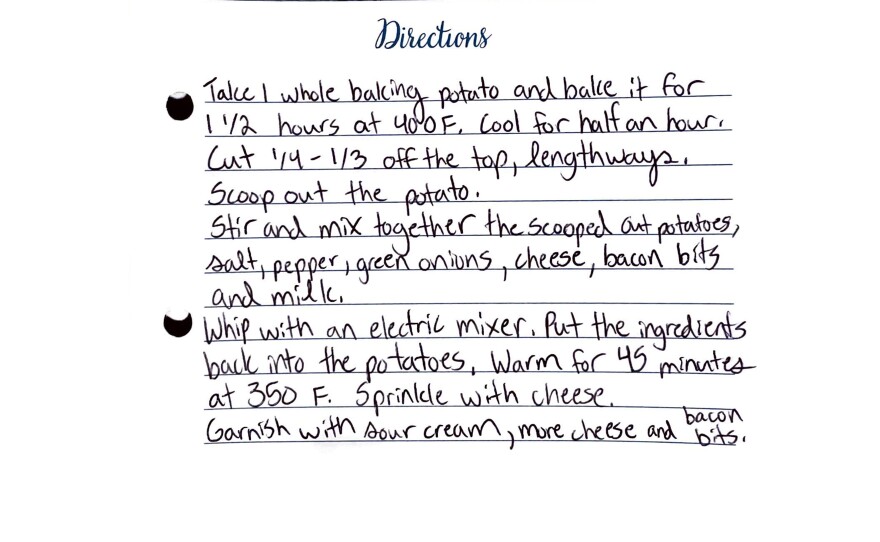

Jordan and Mia Reed are potato growers in Pasco, Washington. They mainly grow hundreds of acres of potatoes for fast-food french fries.

They feed their potatoes directly to processing factories with trucks right out of the field, and the spuds never go to a shed for storage. Nearly 24 hours after their potatoes come out of the ground, they’re made into frozen french fries.

The Northwest is one of the top leaders in potato production in the United States. Idaho is ahead in acreage, but Washington and Oregon’s Columbia Basin grow more tons per acre, said Dale Lathim, with the Potato Growers of Washington. The organization also covers growers in Oregon.

Jordan Reed said the modern potato varieties he grows are very different than the ones on a Thanksgiving table.

“I don’t think the average consumer realizes that there's a difference between all the varieties, and how much time and research the growing community has put back into getting that perfect box of french fries,” he said.

Reed said their family’s favorite potato dish is twice-baked potatoes. They use a different variety of potatoes for that dish — rather than the Shepodies and Rangers that they grow to make french fries.

This year was a bit tough for the Reeds. This spring, some of the processors cut contracted acreage from the farmers’ expectations. The french fry makers didn’t need as many potatoes as they’d contracted, Reed said. By that time, he’d already invested a lot in preparing the ground for spuds. He had to move to growing beans, because processing plants didn’t want all the potatoes he had planned to plant.

“When you put inputs into the farm to raise potatoes and then you raise beans, it doesn't matter how good of beans you get, it won’t offset the costs of the inputs on that farm,” he said.

A harvest that ran late also put pressure on the crops. Things like fertilizer applications are timed out for a specific harvest window. When that window lengthens out, it can put more pressure on the plants.

“The longer the crops are in the ground, the more money you put into it to keep making it a viable commodity,” Reed said.

Mia Reed, Jordan’s wife and business partner, said things seemed simpler when her father was working farms. Right now, there are a lot of pressures on farmers, like low commodity prices and high costs for things like fertilizer, tractor parts and chemicals.

“We struggle sometimes to make ends meet, and keep going and finding the land and finding the contracts,” Mia Reed said.

Jordan Reed said he hopes American children and young adults keep going into agriculture. The Reeds have three children themselves — ages 16, 14 and 11.

“I think there’s a lot of us parents that look at it and say, ‘Why would we want our kids to go through that?’” he said. “I hope it never gets to where ag families are pushing the next generation away because it’s so difficult.”