App Helps Crews Protect NW Forests From Wildfires

Listen

Some foresters say many Northwest forests simply have too many trees. That makes them more prone to disease, insects – and most worrisome of all – mega-fires. But what’s the best way to thin out forests and bring these areas back to more natural conditions? Turns out, there’s an app for that.

This hillside in Central Washington is covered with trees, mostly Douglas fir with some pine sprinkled in. Their canopy acts as an umbrella, effectively blocking the fat raindrops starting to fall from the sky.

And that’s a problem. This forest needs more open spaces. Forester Rod Pfeifle with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is intimately familiar with this land.

“The last harvest in this stand was 35 to 40 years ago. We realized we need to do something with these stands, or we’ll lose them all to insects, disease, and wildfire,” Pfeifle said.

The goal today: Decide which trees need to be cut down.

“We’re trying to restore these stands to a condition that is more resilient and sustainable than they are right now,” Pfeifle said.

Forest managers say 100 years of keeping forest fires off the landscape in the age of Smokey Bear has meant many forests are now too dense. That can worse problems like insect infestations and wildfires.

In a recent report, The Nature Conservancy found about 30 percent of all forests in Eastern Washington need to be restored.

There are many ways to thin forests. But how do forest managers know what they’re doing is actually returning these dense areas to their historic conditions?

That’s where the science comes in. And Android tablets.

Derek Churchill is a researcher at the University of Washington. He and his team have developed a system that uses data points to help crews know they’re on the right track.

“We take places and reconstruct them to 1890 or 1900, when we had active fire regimes before forests were logged. It’s like forestry archeology. From that we develop quantitative targets we’re using to restore the stand today,” Churchill said.

Quantitative targets like: How many trees should be grouped together between the open spaces? And how big should those clumps be?

Reese Lolley enters information into an application that helps forest managers decide which trees to cut down and which trees to leave when they’re thinning forests. The goal is to restore the areas to their natural conditions.

Photo credit: Hannah Letinich

Basically, Churchill’s app translates complicated statistics into practical information for the people on the ground who are actually deciding which trees to cut down.

“It takes an analytical approach and makes it straightforward in the woods,” Churchill said.

Today, crews from various conservation groups, state and federal agencies have come to a workshop hosted by The Nature Conservancy to learn how to use the app.

“So you’ll get in your team. You’ll get your paint, and then we’ll head out. Does that make sense?” Churchill said.

Each group gets a 5-acre plot to test out the new system. For many of the experienced forest thinners, Churchill said the new system will be a little different. They may feel like they are leaving too many trees standing, or they may feel like they are chopping down too many.

The app counts how many clumps of trees the groups are leaving. If they are cutting fewer trees than the goal, that section of the list turns red. If they are targeting too many trees, then that section turns yellow.

“If you’re feeling a little bit uncomfortable that’s good,” Churchill said. “The goal of this is, this is training. We’re going to make some mistakes or not do it perfectly, and that’s okay.”

The crews grab neon-orange spray paint and head to their plots. They survey the trees around them and decide what will be best for the stand.

Pfeifle’s group encounters a dense stand of trees on a hillside. That means they have to cut down more trees to get to their goal. They’re aiming to leave about 40 trees per acre standing and to create more openings.

The trees have thin crowns — so if there’s too much thinning, they could get blown over in the wind. So the team decides to leave more groups of trees standing, instead of a single tree here or there.

“I still think we’re going to find plenty of gaps, but this is kind of a weird little microsite really,” Pfeifle said.

So they start marking which trees to leave. Trees without a ring of orange paint will be cut down this spring and summer.

They call out the number of trees they spray paint and the size of the tree’s diameter. Then they record it in the app.

That lets them know if they are on track to restore the area to its natural amount of trees.

Pfeifle’s goal is to come back into this area in 20 or 30 years to thin the stand out even more. Too much thinning now could cause smaller trees to blow over in a severe windstorm.

“Mother nature didn’t space trees all out evenly. Frequent fire created clumps and mosaics, too. Hopefully we’ll be somewhere close to that when we get done,” Pfeifle said.

When fires do come through this area — and they will, because they’re supposed to — the flames won’t knock out the entire forest. The fire will actually help the area thrive.

Copyright 2016 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Power utilities say Northwest region needs to better prepare for extreme cold

A wind farm. (Credit: Roberta Schonborg / Flikr Creative Commons) Listen (Runtime 1:00) Read Looking back on this past winter, some Northwest utilities have noticed they were really close to… Continue Reading Power utilities say Northwest region needs to better prepare for extreme cold

Pickle-shaped sea creatures popping up along the NW coast, why it’s important

Scientist Kris Bauer measures a pyrosome that was caught in a net aboard the Bell M. Shimada in May 2022. (Credit: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network) Listen (Runtime 0:59) Read… Continue Reading Pickle-shaped sea creatures popping up along the NW coast, why it’s important

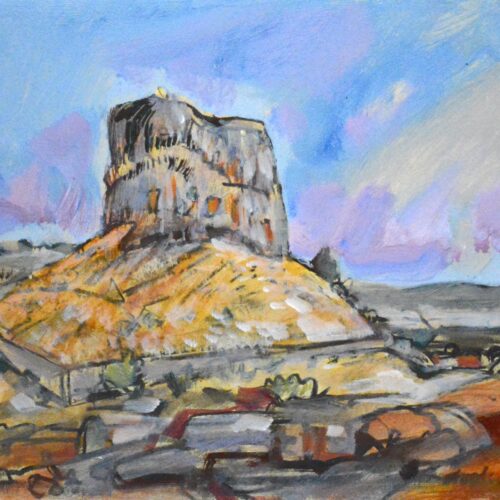

Art exhibit showcases the beauty of the mighty Columbia

Hat Rock, 2022, acrylic on panel, by Erik Sandgren (American, b. 1952) is on display at the Maryhill Museum until Nov. 15. (Courtesy: Maryhill Museum) Listen (Runtime 0:56) Read The… Continue Reading Art exhibit showcases the beauty of the mighty Columbia