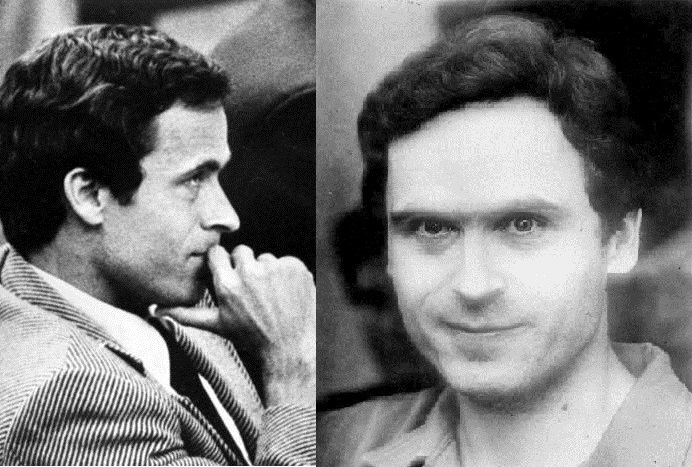

TV Review: The Ted Bundy Tapes Show Uneasy ‘Conversation With A Killer’ From Washington

Read On

It seems everyone in the Pacific Northwest or Utah has a Ted Bundy story. Either you have your own story or someone close to you has one.

I’ve found my own connections, including revelations while watching “Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes” on Netflix. My college friend’s mom was a teenager in the 1970s, and was almost a victim of Bundy. While watching the documentary, I got a text from my own mom, a Utah teen back then whose band teacher found the remains of a victim and, for a moment, was a suspect. As a graduate student at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, I did research for a serial killer novel, only to discover Bundy’s violent impact on the campus. Another friend from South Dakota wrote to me about a high school trip to Florida and seeing the “drunk and obnoxious” protestors in the weeks before Bundy’s execution on Jan. 24, 1989.

Because there are many people with stories about Bundy, he makes good fodder for new shows such as Conversations with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. The four episode Netflix documentary released on the 30th anniversary of Bundy’s death by electric chair, the same day the Bundy biopic Extremely Wicked, Shockling Vile, and Evil premiered in Utah at the Sundance Film Festival. Joe Berlinger, best known for his documentaries on the West Memphis 3, directed both the documentary and the Zac Efron-starring feature, which has yet to be released to the general public.

The documentary features interviews with living law enforcement members, legal representatives, journalists, and a strong interview from the woman whose abduction secured Bundy’s first kidnapping conviction in Utah.

Berlinger mixes these new interviews with Bundy’s own voice from conversations collected during his time on death row, and archival footage of Bundy’s Florida murder trials. Berlinger exhibits a deft eye in editing what amounts to research for his feature project. The interviews — whether we see the subject or only hear them — flow into archival footage with ease. No scene takes over another and every voice is made distinct. While the central focus of the documentary is on these tapes, Berlinger doesn’t linger on them. He allows one member of Bundy’s defense team to call Bundy out for cross examining a police officer in order to relive the goriest minute detail of a crime scene.

There are arguments that this overexposure does what Bundy wants: giving him attention and focus even after death. And despite a section of the documentary discussing Bundy’s supposed attractiveness during his trial, Netflix issued a statement saying no woman should think Bundy is “hot.”

Bundy’s victims are left voiceless for the most part, but Carol Daronch, the Utah woman who escaped from Bundy, speaks for those women who were not so lucky. While Berlinger perhaps doesn’t spend enough time examining the lives of each victim, he purposely avoids placing any blame or shame on the victims, or romanticizing the murderer, as Berlinger’s feature film is already criticized for doing. It’s something of a trade off, and it works well here. Wider audiences will have to wait until later this year to see if Berlinger is able to continue that nuance in his feature film of this same story.

It is difficult to separate how well-made the documentary is from the harrowing content. One sign of a good documentary is that the filmmakers become as invisible as possible and let the material they gather tell the story. Berlinger does this and saves one of the biggest shocks for last. The final statement from the Florida judge who condemned Bundy’s crimes is shown in full, with the judge essentially saying Bundy was not that different from any other white, male of his day. The judge ends by commenting that he liked and would miss Bundy.

That statement is why Bundy movies and documentaries continue to be made and watched. As true crime writer Ann Rule wrote, Bundy was the stranger beside her. “I was one of many, all of us intelligent, compassionate people who had no real comprehension of what possessed him, what drove him obsessively,” Rule wrote in her book about Bundy. He was too close for many people, once the world knew who he was. The lesson this documentary reminds us of is that we don’t entirely know the people we encounter, the people who drift into and out of our lives, and sometimes we get a rude awakening about someone we might have cared about or just someone we knew briefly by happenstance.

Berlinger’s success as a documentarian is putting the living, breathing people who have survived such monsters right in our faces to show that real human evil can be beaten.

Copyright 2019 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

On Asian America: Past And Present Stories Of Living In The Rural Northwest

On Asian America examines the rise in anti-Asian sentiment and it’s history in the Northwest. This episode lookes at historically violent acts against Chinese workers in the rural Northwest from the Hell’s Canyon Massacre to mobs pushing out the Chinese in small towns. You’ll also hear from those of Asian descent who share their experiences living in rural areas and how they are treated. This special is a collaboration with Humanities Washington, KUOW and Spokane Public Radio.

Scrutiny Mounts Against Legacy Of Northwest Missionary Marcus Whitman

For generations Marcus Whitman has been widely viewed as an iconic figure from early Pacific Northwest history, a venerated Protestant missionary who was among 13 people killed by the Cayuse tribe near modern-day Walla Walla, Washington, in 1847.

Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

In this Past as Prologue essay, WSU Professor Karen Phoenix explains the history of the shipping container and its Spokane ties.