Lengthy Detention Of Migrant Children May Create Lasting Trauma, Say Researchers

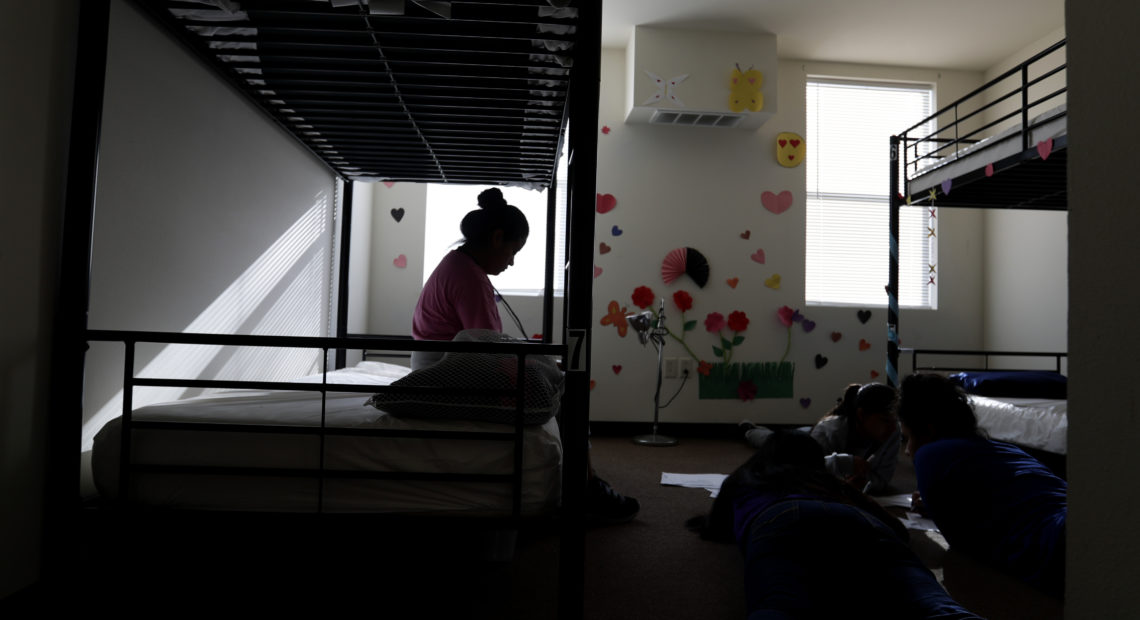

PHOTO: When children are held for long periods away in detention centers, such as this center for migrant children in Carrizo Springs, Texas, they may suffer psychological harm. CREDIT: Eric Gay/AP

BY RHITU CHATTERJEE

This week, the Trump administration announced a new regulation that would allow it to detain migrant families who have crossed the U.S. border illegally for an indefinite period of time. The new rule aims to replace the Flores agreement, a 1997 court settlement which limits the amount of time that children can be detained by the government to a maximum of 20 days.

But psychologists say that indefinite detention could have a lasting impact on the development and mental health of these children.

“If the regulation goes through and we hope it will not … we’re going to see additional harm done to children,” says Luis Zayas, a clinical social worker and psychologist and the dean of the Steve Hicks School of Social Work at the University of Texas at Austin.

A recently published study in Social Science & Medicine found that 32% of children at a detention center showed signs of emotional problems. The study involved interviews with 425 mothers of children at the detention center, who filled out a questionnaire about mental health symptoms in their kids.

“Overall, we found high rates of emotional distress in these children,” says Sarah MacLean, an author of the study and a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, in New York.

They showed symptoms like, “wanting to cry all the time, wanting to be with [their] mom, conduct problems, such as fighting with other kids, or having temper tantrums, peer problems, so not having a lot of friends, or only wanting to interact with adults,” she adds.

These symptoms were far more common in the children who were recently reunited with their mothers after being forcibly separated from them once they crossed the U.S. border compared to children who hadn’t been separated from their parents.

MacLean also interviewed 150 kids aged nine to 17 years at the same detention center about whether they were experiencing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.

These are symptoms “like re-experiencing, having flashbacks of trauma or nightmares about the trauma,” explains MacLean. Symptoms also include low mood and “an increased sense of arousal,” she adds. “So that means, if there’s a loud noise, suddenly they’re jumping out of their seat, which someone without PTSD wouldn’t normally do.”

Her study found that 17% of the children showed significant symptoms of PTSD. “And [they] likely would be diagnosed with PTSD if they saw a physician,” says MacLean.

And, most Central American children in U.S. immigration detention centers have already experienced layers of trauma by the time they arrive here, says Zayas. The trauma “that happened in their home countries — the violence, the extortion, the police complicity, government inaction,” he says. “Then they’ve they’ve trekked through Mexico, where they’ve seen some great horrors — rapes and assaults and violence and death.”

MacLean’s study couldn’t distinguish whether the emotional problems and the PTSD experienced by the children at the detention center were because of their past traumas or from the trauma of detention, or a combination of everything. But her findings confirm previous studies done in other countries.

Research by the Australian Human Rights Commission found that children in detention facilities suffer from mental disorders and the level of mental health problems increases with time in detention, says Kristen Torres, the director of Child Welfare and Immigration at First Focus on Children, an advocacy group in Washington D.C. The study found that 34% of children in detention had diagnosable mental health disorders, and nearly 85% of children and parents said their mental health was affected by detention, with sadness and constant crying as their most common symptoms.

A 2004 study in Australia found that all children and adolescents in detention met the criteria for PTSD, major depression and suicidal thinking.

Zayas has done psychological evaluations of children and families in immigration detention centers. “In nearly every child I’ve seen over the past five years, there’s been some detrimental effects on their mental health,” says Zayas. “I met an 11-year-old boy, who began to wet his bed after the strain of detention and having been held in medical isolation with his mother, because she had gone on a hunger strike. I’ve had suicidal teenagers, who’ve saw no point in living anymore, because they don’t know what their future holds.”

Normally, being with their parents protects kids psychologically and helps them cope with trauma and stress. But that protective effect is often eroded in detention, says Zayas, because parents are stressed by detention, too.

“Parents who are under the stress of detention not only transmit that stress and anxiety, and depression to their children, but their roles as parents are upended,” he says.

Their authority is undercut, and they can’t comfort their children as well.

Studies of mothers in family detention centers, show that they had high levels of hopelessness and depression, says Torres. “They were unable to have a proper parent-child relationship within the detention center,” she says

Children and families in detention feel threatened by their environment, says Zayas. “It’s not the normal experience of children to be living behind walls with barbed wires on them,” he says.

“There are prison guards who loom large, who are often gruff and not sensitive, because they are prison guards. They’re not guardians,” says Zayas.

And he says, the guards sometimes, “intentionally or inadvertently frighten children, say[ing] things to them like ‘Well you we’re going to deport you,’ or, ‘You’re going to be deported,’ or, ‘You’ll never leave this place or something’s going to happen to you.’ ”

Research shows that chronic stress and adversity affects the development of kids’ brains.

“It affects regions of the brain and functions that have to do with cognition, intellectual process, with judgment, self regulation, social skills,” says Zayas. “And it really troubles me that there will be thousands and thousands of children who will be scarred for life.”

Some children might bounce back once they’re released from detention, he says, but may will need long-term mental health care to recover from their traumas.