Metropolitan Opera Faces ‘One More Catastrophic Crisis’ As Employees Must Work With Domingo

BY ANASTASIA TSIOULCAS

Next Wednesday evening, Plácido Domingo, the opera megastar who has recently been accused of sexual misconduct by 20 women, is scheduled to start a run of performances of Verdi’s Macbeth at the most famous opera house in the United States: New York’s Metropolitan Opera. The sold-out first show also features soprano Anna Netrebko, another of the operatic world’s most bankable stars.

Many fans and fellow artists have rallied to Domingo’s side in the wake of the women’s allegations, which were published by the Associated Press in two reports. Netrebko posted on Instagram last month that she is happy to “share stage with fantastic Plácido Domingo!” In a statement to NPR last month, Domingo said: “I believed that all of my interactions and relationships were always welcomed and consensual.”

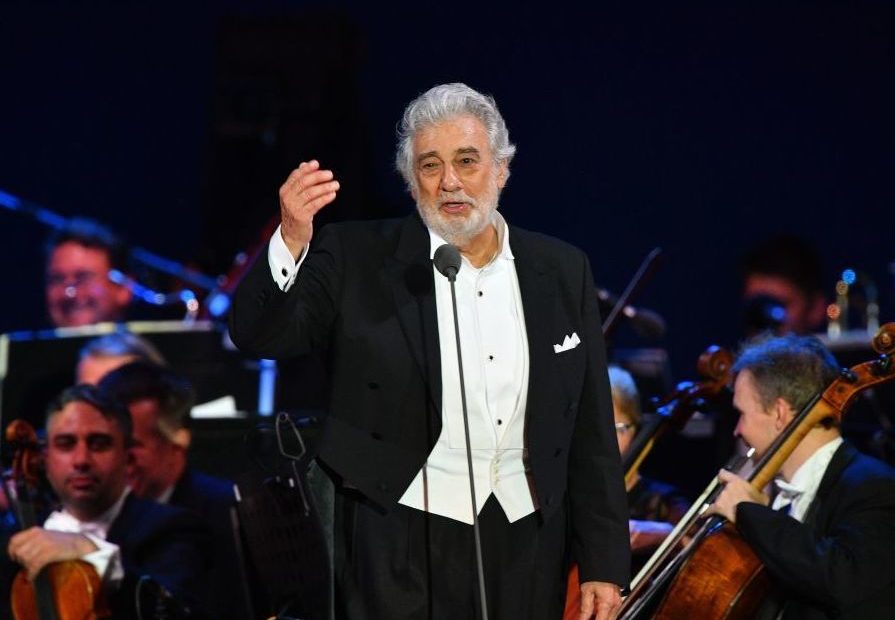

Opera star Plácido Domingo performing in Szeged, Hungary, on Aug. 28. CREDIT: Attila Kisbenedek/AFP/Getty Images

The Met calls Macbeth a “powerful musical interpretation of Shakespeare’s timeless drama of ambition and its personal cost,” and this production is a chance for audiences to demonstrate their support for the singer.

But not everyone inside the Met is happy. A number of longtime employees at the opera house have told NPR that they are furious that the New York company is continuing its association with Domingo. These staffers believe that their employer has a specific responsibility to take allegations of sexual misconduct seriously after the downfall of James Levine, the Met’s former music director of four decades, who has been publicly accused of sexual abuse by nine men. Levine was fired by the Met in March 2018. (Levine then sued the opera company, which filed a counterclaim; the two sides reached a settlement for an undisclosed figure last month.)

Four current Met employees spoke to NPR about the Domingo situation on the condition of anonymity because, they say, they fear retribution.

They insist that they do not want to harm the Met as an institution or impair the financially precarious art form of opera. But all four say — in comments that echo some of those from the women who spoke to the AP about Domingo’s alleged behavior at LA Opera, Houston Grand Opera and what was then called Washington Opera, in Washington, D.C. — that it was “common knowledge” at the Met that Domingo would make sexual overtures to women there.

None said that they had directly experienced any misconduct, but several say they feel that the power dynamic between Domingo and rank-and-file employees is so overt and distorted that it has created an untenable work environment, and that they felt compelled to speak up.

“Everybody knows that Domingo is a womanizer and that he could be persistent,” one of the Met employees, who has worked at the opera for decades, told NPR. This person also said that women working at the Met have known to avoid one-on-one situations with the singer — the same kind of strategy that a number of the women interviewed by the AP said had been deployed at other opera houses at which Domingo was appearing.

The same source also told NPR that there were a number of women at the Met who in the past have gone so far as to change their work schedules — denying themselves artistic and potentially career-furthering opportunities of working with the long-revered and influential singer — specifically to avoid having to interact with Domingo. “A lot of that stuff started happening in the 1980s,” this employee said. “As he got older, it was less of a big deal. But still, women knew.”

Another Met employee, a member of the orchestra, said that at least one person has already called in sick for rehearsals and performances of Macbeth to avoid working with Domingo, and said that they personally felt “livid” for having to perform alongside him. “I feel queasy in the pit during rehearsals, seeing him onstage,” the musician said. “Especially given that the Levine debacle is still so fresh, the Met had an even greater responsibility to show that it had evolved. Instead, here’s just one more catastrophic crisis — and it seems that at the Met, sufficiently powerful, popular men are beyond reproach.”

Another employee said, “I wish he wasn’t here. I think the Met is the face of opera in this country, and maybe even in the world — and having him on that stage sends a message that I don’t want to be sending. I think a majority of our colleagues at the house feel similarly to how I’m feeling. But it’s also confusing. People love him — Plácido is warm, generous and kind to individuals — but he was also not at all that to a not-insubstantial number of people.”

In his statement to NPR last month, Domingo called the allegations in the AP reports “deeply troubling, and as presented, inaccurate.” In a second statement sent to NPR earlier this month, his spokesperson, Nancy Seltzer, called the AP’s reports an “ongoing campaign to denigrate Plácido Domingo.”

When contacted for this story, Seltzer asked that questions be submitted by email. In response to NPR’s inquiries, she sent this statement: “Plácido Domingo has been greeted by his colleagues at the Met in a warm and professional manner, as one would expect for an artist who has performed there for more than five decades.”

Seltzer continued: “As has been stated in previous statements to the press, anyone who knows Mr. Domingo or who has worked with him knows he is not someone who would intentionally harm, offend or embarrass anyone. The outpouring of support for him from singers and musicians around the world attest to this fact. He is focusing on giving the public the best possible performance.”

But Met employees are questioning the institution’s commitment to statements it issued in the wake of the Levine accusations, including one released when the conductor was terminated from the opera house, which said: “We wish to provide the assurance that the Met is committed to ensuring a safe, respectful and harassment-free workplace for its employees and artists.”

There have been no public accusations of misconduct by Domingo since Macbeth has gone into rehearsal. However, Met artists and workers say that they still feel uncomfortable, given the Levine situation. One of the Met employees who spoke to NPR, and who was at the Met for a long portion of Levine’s tenure there, said, “Did that statement [from the Met] mean anything? The lesson I’ve taken away is that if you’re powerful enough, people shouldn’t bother to make a complaint. Nothing will be done.”

“When Jimmy [Levine] was our music director,” another of the sources who also has been with the Met for decades said, “there were all kinds of rumors, but no one came forth. We had to sit through it for 40 years. But when there were allegations, management got rid of him.” Afterwards, this employee continued, “We thought, ‘OK, after all this time, after we have endured so much, we’re finally going to get protected.’ But nothing has changed — the culture is so deeply embedded.”

The sources told NPR that rank-and-file employees at the opera house, as well as many solo cast members, have been sent to anti-sexual harassment training since the allegations against Levine were made public, but that it rankled them to then see Plácido Domingo — who continues to be a powerful figure in the opera world — on the Met’s stage. (Along with singing in Macbeth, Domingo is scheduled to perform in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly in November.)

A current member of the Met orchestra described feeling angered upon seeing an HR representative carry anti-sexual harassment training materials into a rehearsal room at the opera house, after rehearsal had ended and Domingo had left.

Since the AP published allegations from the 20 women, a number of prominent American classical music and opera institutions have canceled engagements with Domingo, including San Francisco Opera, the Dallas Opera and the Philadelphia Orchestra. The Philadelphia Orchestra’s current music director is Yannick Nézet-Séguin — who has also been the music director of the Metropolitan Opera since the beginning of the 2018-19 season. Nézet-Séguin did not respond to NPR’s request for comment, made through his management.

By contrast, the Met has said that it will wait for the results of an investigation by LA Opera. That investigation has barely begun; according to the Los Angeles Times, employees at the California opera house just received an introductory letter from the lead investigator, Debra Wong Yang, this Monday. Similarly, no European institutions or opera houses have canceled scheduled performances by Domingo.

“I understand that it’s easier for Philadelphia or Dallas or San Francisco to pull him,” one of the Met employees told NPR, referring to the fact that those were each single concerts as opposed to the Met’s extended schedule of opera performances, and also alluding to Domingo’s long association with the Met: He’s sung there more than 700 times. “But I find it troubling that we have the same music director as Philadelphia, and can’t make the same decision,” the employee continued. “I don’t think it’s Yannick — I believe it’s the board [who is keeping Domingo on at the Met].”

The current chairman of the Met’s board, Ann Ziff, is an extremely influential figure within the arts world. She’s served on the Met’s board since 1994 and gave a record $30 million to the opera company in 2010. She also has deep ties to Domingo’s work: in 2015, the philanthropist joined the board of LA Opera — the house that Domingo helped found in 1986 and where he has been general director since 2003. Ziff was also one of the funders of a gala held in April that celebrated the 50th anniversary of Domingo’s debut at the Met. Single tickets for the event started at $2,500.

The Met’s production of Macbeth is being underwritten by several prominent donors, including Paul M. Montrone, who is president emeritus of the Met board.

The Metropolitan Opera is a complex organization: It employs workers who belong to several unions. Their job titles range from orchestra players and chorus singers to costumers, makeup artists, ticket sellers and stagehands. NPR attempted to obtain comments from several union leaders whose members work at the Met; most did not respond, and one referred NPR to the Met’s publicity department. However, one of those unions, the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA), which represents the chorus, soloists, stage managers, directors, dancers and choreographers at the Met, announced earlier this month that it had retained its own counsel to conduct a separate investigation into the allegations against Domingo.

NPR requested comment for this report from Peter Gelb, the Metropolitan Opera’s general manager. As with Domingo’s representative, the Met also asked that questions to Gelb be submitted by email. In response, the company said in an email, “The Metropolitan Opera has nothing further to add to our initial statement at this time,” and then repeated the statement it sent to NPR on Aug. 13, which read:

“We take accusations of sexual harassment and abuse of power with extreme seriousness. We will await the results of the investigation into Plácido Domingo’s behavior as head of the Los Angeles Opera before making any final decisions about Mr. Domingo’s ultimate future at the Met. It should be noted that during his career at the Met as a guest artist, Mr. Domingo has never been in a position to influence casting decisions for anyone other than himself.”

The Met employees who spoke to NPR say that, due to the opera house’s recent experience with Levine, it has a particular duty to take the needs of its artists and staff seriously. “We have so much history with Plácido, it means, I think, that we have more of an obligation to respond,” said one of the sources. “Additionally, suspending someone pending a misconduct investigation is pretty standard; it’s a measure that’s there to protect everyone, including Plácido. He wouldn’t have to face people, and people wouldn’t have to face him. As it is right now, it’s a very awkward situation.”