Climate Stewardship Connects Eastern Washington Faith And Farming To Legislative Action In Olympia

Listen

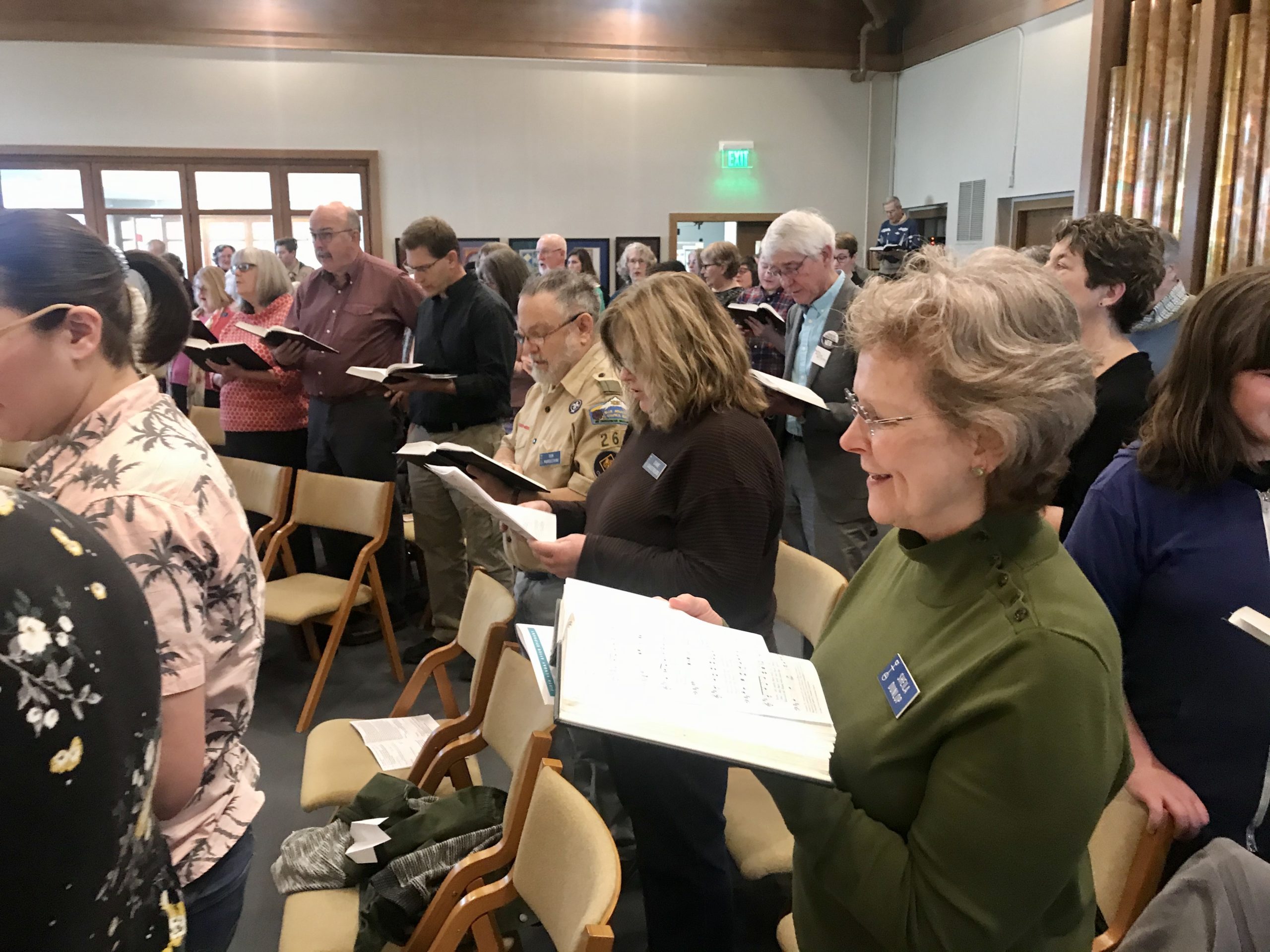

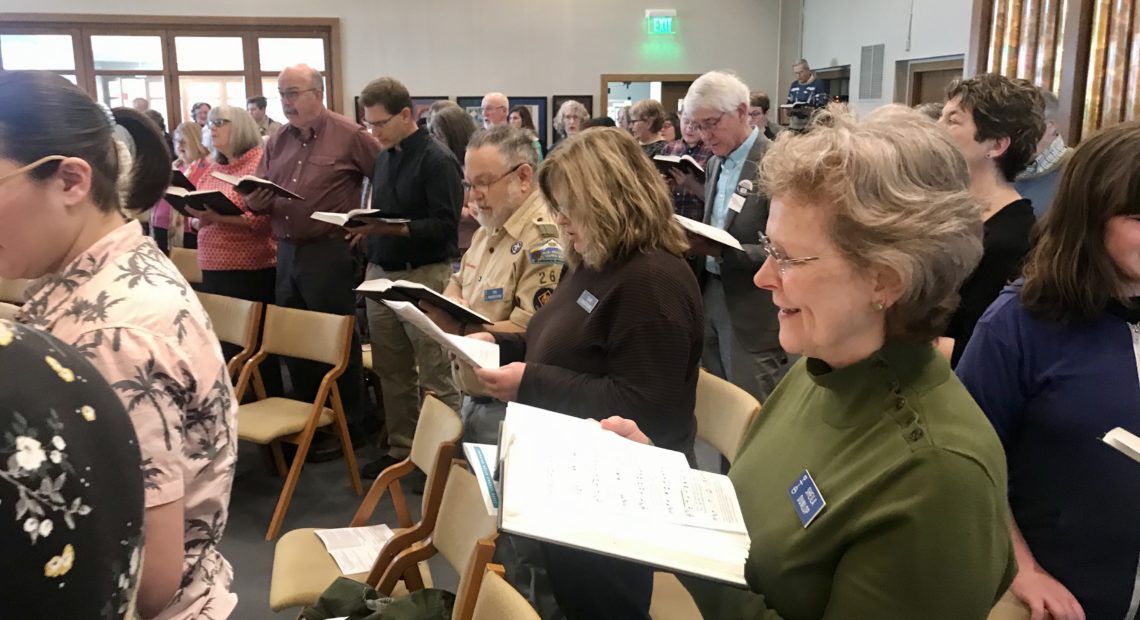

As the clock nears 10 on a recent Sunday morning, people meander to their seats inside Richland’s Shalom United Church of Christ. Piano music echoes throughout the hall as friends greet each other and shuffle through the morning service’s program.

This day’s main focus (interspersed with Scout Sunday) is a deep talk about climate change.

“It’s all going to work,” jokes Rev. Steve Eriksen, as scouts clad in khaki uniforms sit in rows behind environmental advocates.

Climate change isn’t a new topic for the progressive church, but it is perhaps tinged with new urgency. Survey results from the Pew Research Center show that congregations are delving into environmental awareness recently.

“Climate change is the most important moral issue of this generation,” Earth Ministry’s LeeAnne Beres tells the Shalom congregation.

She says science and religion go hand-in-hand: science provides the what, while religion speaks to the why: the morality behind decisions that affect the natural world.

“Science alone won’t save us. We have to have the courage and the will to act,” LeeAnne Beres says. “The faith community has the language and the ability to articulate values in a way that can cut across political and partisan divides.”

It’s that language that the faithful are hoping to use to push for several environmental bills in the Washington legislature this session.

Bills like the sustainable fields and farms bill, known as second substitute SB5847 in the legislature. It’s a bipartisan effort that would give grants to farmers who volunteer to sequester carbon in their soils or use farming practices that reduce the burning of fossil fuels or other heat-trapping emissions.

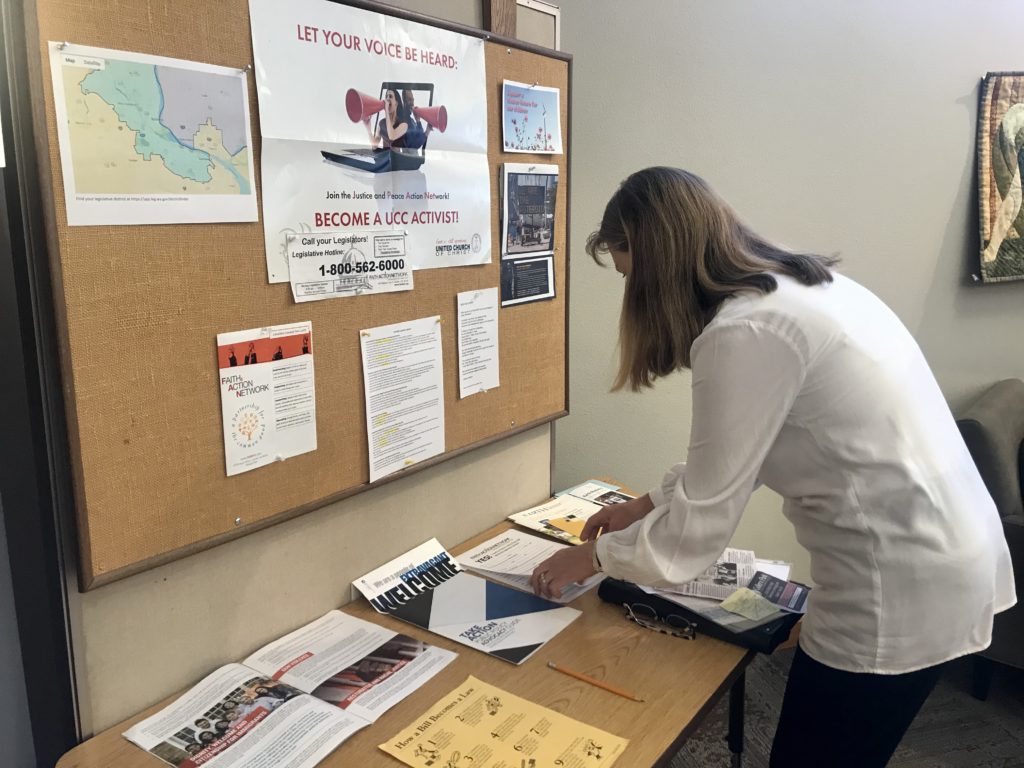

Shalom United Church of Christ member Lora Rathbone helps run the church’s social action table. She answers people’s questions about environmental advocacy and provides information about legislative bills the church supports. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

“This is voluntary, it’s not mandatory. So, for those agriculture folks that would like to test the waters on carbon (sequestration), this’ll help them do that,” said Sen. John McCoy, a Democrat from Tulalip.

As far as religious lobbying goes, both the Pacific Northwest Conference of the United Church of Christ and Quaker Voice on Washington Public Policy testified in support of the bill.

Baby Steps

Not far from some of Washington’s most productive crop fields and dairy pastures, 15 people sit in a circle underneath the stained glass inside St. Michael’s Episcopal Mission near downtown Yakima.

They’ve gathered for a Faith Action Network advocacy day during this legislative session.

“The idea is to remember ‘Faith Action Network’ and what we can do going forth from this meeting,” the Rev. David Hacker says.

On the agenda in the environmental breakout session: explaining what environmental bills they think would make a difference. They talk about social justice, divestment from fossil fuel companies, and the sustainable fields and farms bill.

For Lora Rathbone, the sustainable fields and farms bill just makes sense. It’s something that can help the environment and is supported by people in more conservative eastern Washington.

“We’re up against this fight that a lot of people (are) still not recognizing that climate change is a human-caused problem – and that we can do something about it. And, in our faith communities, not everyone recognizes that this is something we can do in our churches,” Rathbone tells the group gathered for advocacy day.

Shalom United Church of Christ member Lora Rathbone helps run the church’s social action table. She answers people’s questions about environmental advocacy and provides information about legislative bills the church supports. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

Rathbone, a member of Shalom UCC in Richland, says it’s all about baby steps toward protecting the planet.

“Change comes slowly,” Rathbone says. “The more people hear about something, people will often warm up to a new idea with time.”

She says this bill is a step in the right direction.

Cover Crops

Eastern Washington farmer Jim Baird agrees. His ecofarms aren’t connected to any church, but he calls climate change the fight of this era.

“I know that farming and bad farming practices are an awful lot of the problem, and I believe that we can be even more a big part of the solution,” he says. “I think a lot of people don’t realize how important agriculture could be in mitigating climate change.”

He recently testified in Olympia to support the sustainable farms and fields bill. Now, he walks across a large field outside Royal City in Grant County.

Potatoes recently grew in this soil. Now, two types of mustard and triticale (a hybrid of wheat and rye) form its tidy rows.

The fields Baird manages use these cover crops, or what he also calls “green manure.” Cover crops are planted on fields that have just been harvested. They’re one method in this bill that can help farmers sequester carbon.

“We never leave our soils open. We get something in there just as soon as the last crop is off,” Baird says, looking down at the tiny plants below his feet.

Although cover crops are not a new concept, Baird says more farmers are using them. Immediately, they help prevent nutrient-rich soil from blowing away in the Mid-Columbia’s strong winds. Over time, they make the soil healthier and crops more productive.

They’re also a proven way to sequester carbon and improve soil health. Baird says as he’s used more cover crops over the last 10 years, he’s sequestered up to 14 tons of carbon per acre.

“As we add organic matter, we are pulling some of that carbon back into the ground, and we’re helping mitigate some of those climate change issues,” Baird says.

Farmer Jim Baird uses cover crops like mustard and triticale (a hybrid of wheat and rye) to improve the nutrients in his soil and to sequester carbon. Over the past 10 years, as he has intensified planting cover crops, he’s sequestered up to 14 tons of carbon per acre. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

While the bill saw diverse support from the Farm Bureau to the Audubon Society, other groups worried it only supports large-scale farms, with not enough support going toward organic farms. Other groups raised concerns that it would take money from underfunded agricultural programs.

But, still, supporters say it likely passed thanks in large part to its bipartisan support. It now goes to the governor’s desk.

That’s good news to Lora Rathbone, at Shalom United Church of Christ in Richland. Like an environmental evangelist, she stands next to what’s been dubbed the “social action table” during the church’s coffee time, talking to any member who has environmental questions.

“Doing this in a church, where you know that you have a wide variety of people that don’t think the same, we work harder to be more moderate and open-minded about different points of view,” she says. “As opposed to being in an environmental group, where people are thinking the same way.”

History Of Stewardship

According to the non-partisan Pew Research Center, there’s a long history of religion promoting stewardship of the Earth. For example, Pope Francis recently issued an encyclical on environmental protection.

A 2010 Pew survey found 81% of adults, from all major religious traditions, supported “stronger laws and regulations to protect the environment,” while 14% opposed them.

Of the adults who go to a religious service once or twice a month, 47% report their clergy spoke on environmental topics. But only 6% of survey respondents said their religious affiliation changed their views on environmental protection laws.

In Richland, Rathbone does all she can to make environmental advocacy easier for other church members. She distributes handouts about bills the Faith Action Network supports. She hands out pamphlets to help people call a hotline and quickly show their support for bills. She answers drafts letters congregation members can sign.

“(Advocacy) scares people, regardless of it being part of church,” Rathbone says after the recent service in Richland at Shalom United Church of Christ. “So, we’re just trying to make calling your representatives as easy for people as possible. Then, once you try it, you realize it’s not that difficult to be heard.”

Shalom’s leader, Rev. Steve Eriksen, says churches are important ways to reach others who may have differing social views. To him, environmental activism is important within religious organizations.

“Creation care is something we’ve all been called to do,” he says. Otherwise he thinks churches would just be social clubs.

“I do want us to be relevant. It’s nice to have friends in the church and to meet together to see one another. But, the church has a higher calling,” he says. “The church is called to make a positive impact in our society and in our environment.”

Related Stories:

Tumbleweeds sold for big bucks on popular home decor website causes chuckles in the Northwest

Tumbleweeds are torched at the Hanford cleanup site in southeast Washington in the early part of this year. (Credit: U.S. Department of Energy) Listen (Runtime 4:35) Read Fire Chief Nickolus

Year-old Northwest potatoes are being dumped in favor of new potatoes

Columbia Basin potatoes move on a belt during harvest in 2021. (Credit: Anna King / NWPB) Listen (Runtime 1:02) Read For two years, Northwest farmers didn’t have enough potatoes for

Fewer Northwest bees shipped to California’s almonds could be a buzzkill for Washington and Oregon crops

Brandon Hopkins, a bee researcher with Washington State University, points May 15 with his hive tool to the new bee larvae cells where baby bees develop in the hive near