What will Election Day look like for AP?

On Election Day, AP will have a team of about 4,000 people known as election stringers dispersed around the country to collect vote counts from county clerks and relay the information by phone to vote-entry clerks who put the information into AP’s vote tabulation system. In prior years, these clerks worked from large vote-entry centers where they took the calls from stringers. This year the process will be completely virtual, which AP started doing for all primary races after March 17, AP’s Director of Elections Brian Scanlon said.

AP’s decision desk has about 60 analysts, race callers and editors who monitor the data as it comes in. As vote counts are reported by states, the decision desk considers the vote tally as well as the types of ballots voters are casting, whether in-person or by mail, alongside the data the team has gathered from VoteCast and other research.

Democratic candidates are more likely than Republicans to make late gains in an election as the final results are tallied — what’s known as the “blue shift” phenomenon. It’s important to remember that early vote counts can paint a very different picture from what the eventual result will be as certain groups of people lean toward a particular voting option.

The Brennan Center for Justice, a bipartisan law and public policy institute, analyzed 2016 data from seven battleground states where any voter could choose to vote by mail: Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Minnesota, North Carolina, Ohio and Wisconsin. It found that white voters and voters over the age of 65 were more likely to cast ballots by mail in those states.

A recent PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll found that 42 percent of Democrats said they plan to vote by mail, along with 34 percent of independents and 19 percent of Republicans. Other reports and polling indicate that many non-white voters trust in-person voting more than mail-in options.

This year amid the pandemic has seen a bigger push for all voters to take advantage of mail voting, but the inconsistency of state requirements for submitting ballots has created confusion and hurdles for voters who don’t have regular access to transportation or mail.

In the end, AP won’t know specific demographic information from the vote count, but the decision team consults its body of research and will only call a race when it determines that the trailing candidate cannot catch up to the leader. The team will monitor top races continuously until they are called, Easton said.

PODCAST: Why voter suppression continues and how the pandemic made it worse

“It’s all part of a collaborative approach,” Scott said. “For first statewide races and the presidency in particular, no one person at AP can call a race. We’ve got to convince each other that it’s ready and we all need to agree.”

What results can voters expect on election night?

Scott would not make a prediction about the timing of election results, but said the competitiveness of a race is one of the biggest determinants of how quickly the race will be called. “If the race is very closely contested, it’s going to take some time. We need to count deep into the vote count to be able to call states,” he said.

In races that aren’t closely contested, often AP will be able to call the winner as soon as the state’s polls close and the initial vote count is reported. If a state has a long history of favoring a particular party or candidate, AP factors in that history with the VoteCast data to determine a winner quickly.

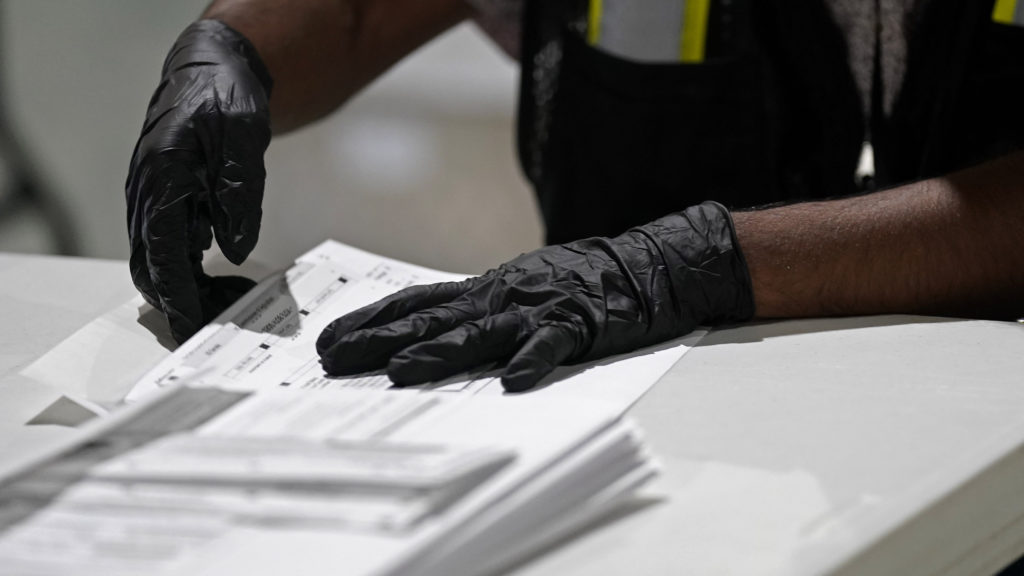

A worker prepares absentee ballots for mailing at the Wake County Board of Elections in Raleigh, N.C. in September 2020. CREDIT: Gerry Broome/AP

AP may decline to call a win or list a race as “too close to call” if a vote tabulation has reached a conclusion without a clear winner, such as if the margin between the top two candidates is less than 0.5 percentage points. The “too close” designation is different from a race that is actively being assessed after Nov. 3. In such cases, the AP will wait for the state to certify a winner.

This year the influx of absentee and mail-in ballots will take more time not because of counting the votes, but mainly because of processing the ballots, Scott said. “An envelope has to be opened. A signature needs to be verified. Things that take place very efficiently when you check into your polling place on Election Day just take a little bit longer when you’re doing it absentee or by mail,” Scott said.

States have different restrictions on when that processing can begin. Some states like Tennessee and Texas allow processing to begin upon receipt of the ballots while others like Rhode Island and Connecticut allow processing to begin several days before Nov. 3 — though the counting of ballots for each of these states cannot start until Election Day. Key presidential battleground states Florida and Arizona have each allowed both processing and counting to begin early, on Oct. 12 and Oct. 20, respectively. Two other battlegrounds, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, do not allow processing or counting to start until the morning of Election Day.

The Washington Post determined that primary races held in 23 states after March 17, when the country began to shut down amid the pandemic, took an average of four days to report “nearly complete results.” Several close races in New York took more than a month to determine a winner.

ALSO SEE: Election-Year News, Podcasts, Regional Debates From NWPB’s Vote2020

The battleground states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Georgia were among the slowest to report nearly complete results during the primaries, taking more than six days according to the Post’s analysis.

“In the 2016 presidential election, AP named Donald Trump the winner at 2:29 the morning after Election Day,” AP’s Executive Editor Sally Buzbee wrote in a column. “In 2004, AP did not call the presidency for George W. Bush until 11:07 a.m. ET, again the day after Election Day. And in 2000, AP stood alone when it assessed the race between Bush and Al Gore and decided it was too close to call.”

A delayed call does not indicate fraud or disaster, Buzbee continued, but rather that the organization is taking time to make tabulations.

“We certainly want to tell the American people — and the world — who has won the presidency as soon as possible,” she said. “But accuracy comes first.”