Composer John Luther Adams On The Arctic Sounds That Shaped His Work

LISTEN

BY KAREN MICHEL

This has been a booming year for composer John Luther Adams. His 2014 Pulitzer Prize-winning orchestral work Become Ocean has been re-released as part of a trilogy. Recordings of new string quartets have just come out. And he’s just published a memoir, Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska. The title was inspired by a line in “Listening in October,” a poem from the late John Haines:

There are silences so deep

you can hear

the journeys of the soul,

enormous footsteps

downward in a freezing earth.

For a young Adams, that freezing earth was Alaska. Adams grew up in the suburbs of the Lower 48, and studied music composition and percussion near Los Angeles. When he went to Alaska, he went as an environmentalist, not a composer. But the state and its scale led him to devote himself to transforming experiences of place into sonic space.

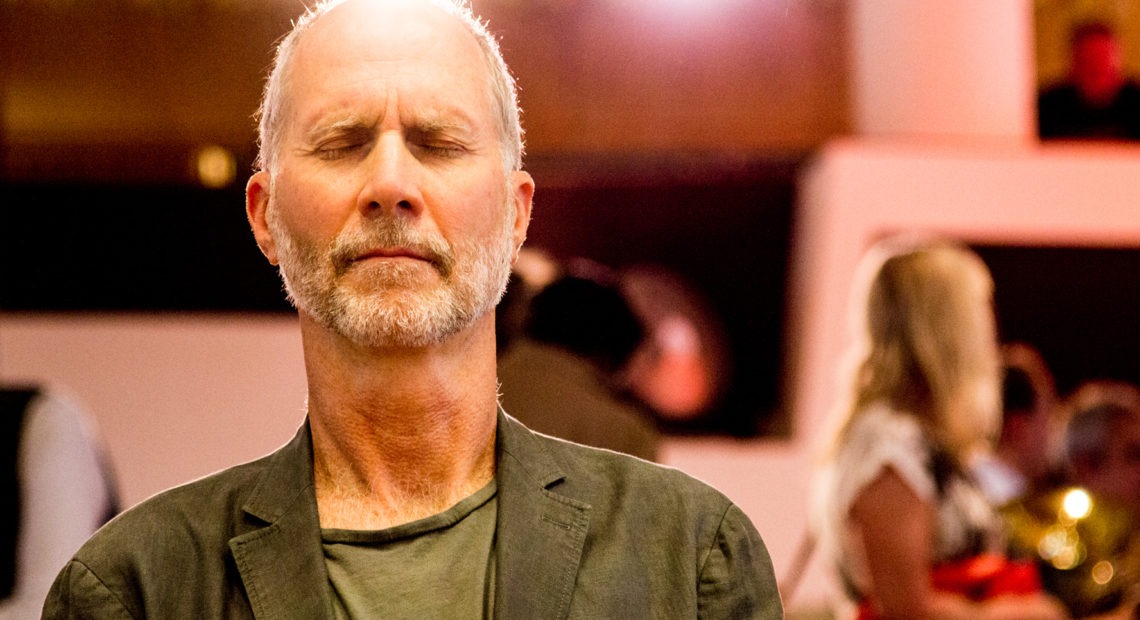

Composer John Luther Adams wrote his memoir, Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska, based on the decades he spent living and working in the Arctic. CREDIT: Pete Woodhead/Courtesy of the artist

“I first went north in the summer of 1975, and from the moment I arrived, I knew that I had come home,” he says. “There was a kind of exhilaration, a sense of possibility, of openness in the landscape that led me to dream of music that somehow reverberated with all of that fire and ice and wind and stone and space and elemental power.”

That sensation is palpable in Adams’ music. Being in the north — truly in it, not in a city but living in the tundra moonscape or in the kind of scrubby pine forest he did — and experiencing its extremes of weather and landscape means getting acquainted with the sounds of never-really-silence. For Adams, the atmosphere produced such works as his Earth and the Great Weather from the early 1990s.

“Silences So Deep: Music, Solitude, Alaska” by John Luther Adams.

In that composition, Adams incorporated the knowledge and voices of Inupiaq and Gwich’in speakers. Among them was Adeline Peter Raboff, who grew up in Arctic Village, a community of 150 or so where winter temperatures dip to 60 below. She describes working with Adams in nearly spiritual terms.

“That’s the thing about his music — it makes you realize that you’re just a part of this huge universe and there are many things that you just don’t know, you don’t understand and you might never,” she says. Raboff says she has no issue with Adams using Indigenous source material — in fact, she asked him to set one of her poems to music.

“My life’s work, my aspiration is to create music that’s entirely outside of culture,” Adams says. “It’s of course a patently ridiculous proposition.”

Adams grew up in the culture of rock and roll. Drums are a big part of his music, which is partly what attracted conductor and percussionist Steve Schick to his work.

“I had never ever heard music like this in my entire life; it was so thrilling,” says Schick, who first discovered Adams in the ’90s. “It was so, kind of, raw. It both appealed to the mind and the ear, but it also appealed to the heart and the whole body, and so I was bowled over by this music.”

When Adams won the Pulitzer for Become Ocean, he was in his early 60s and had just left Alaska. Since then, he and his wife Cynthia have lived in Manhattan, Mexico and Chile. Now they are, as he describes it, in an undisclosed location in the U.S. desert. Among the compositions he’s working on is one he describes as a sort of “eulogy for the Arctic.”

“There’s always more to discover. There’s always more in what we’re hearing than we can process at once. I think what I’m after is losing myself in the music, and that’s what I want for you,” Adams says. “Ultimately I think I’m trying to compose home, a place to live. I want to inhabit the music.”