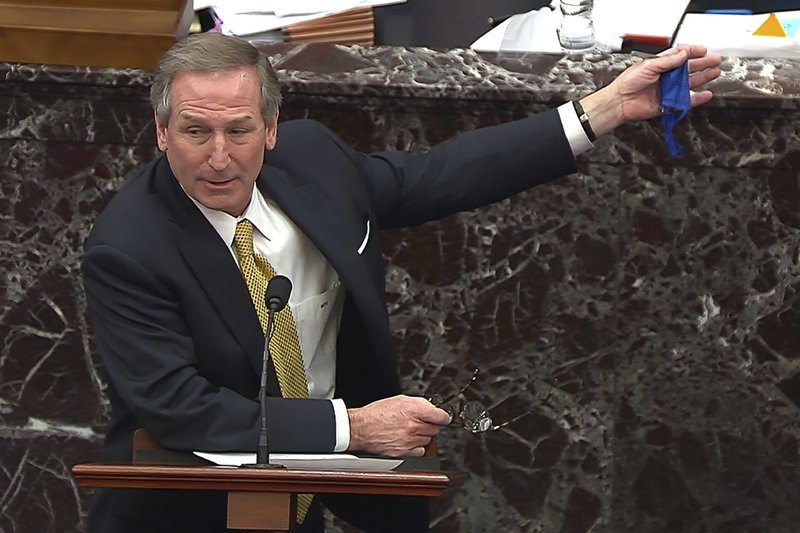

To drive that point home, he played a highlight reel of prominent Democrats urging their own party and supporters to “fight” against Trump. The video, which drew from a variety of political speeches without context, featured House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Vice President Kamala Harris, and Sens. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and Bernie Sanders of Vermont, among others.

Democrats know that politicians from both parties have used the terminology “forever,” van der Veen argued, but were choosing unfairly to punish Trump.

The debate over Trump’s language was similar to a disagreement at the heart of his first impeachment trial. In that case, Democrats and Republicans sparred over what Trump meant when he asked Ukraine’s leader to do him a “favor” by investigating President Joe Biden and his son, Hunter Biden.

The impeachments aside, lawmakers spent four years debating the meaning of Trump’s tweets and comments in speeches and rallies. There was rarely agreement on what he meant, and his speech Jan. 6 has proven no exception.

The politics of it all

As part of their defense, Trump’s attorneys argued that the Democrats’ decision to impeach him was driven by the desire to hurt him politically, and bar him from mounting a comeback.

If the Senate convicts Trump, it could pursue a separate vote to bar him from holding federal office in the future. Trump reportedly considered announcing on his way out of office that he planned to run for president in 2024.

It was clear from the start that it was highly unlikely Trump would be convicted; that was apparent when all but six of the 50 Senate Republicans voted this week that the trial of a former president was unconstitutional.

Still, the defense team argued that Democrats proceeded with the trial anyway in order to exact the maximum political damage to Trump and his supporters.

“Why are we here? Politics,” said Bruce Castor, one of Trump’s attorneys. The Democrats’ “goal is to eliminate a political opponent, to substitute their judgement for the will of the voters.”

Senators’ partisan questions preview the final vote

The partisan nature of the questions senators asked after the defense rested offered a clear preview of where they stand heading into the final vote.

A few of the questions were aimed at clarifying facts surrounding Trump’s conduct on the day of the attack. Republican Sens. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine — two of the six GOP senators who earlier this week voted that the trial was constitutional — asked when Trump first learned the Capitol had been breached, and what steps he took to try to end the siege.

“Please be as detailed as possible,” Murkowski and Collins asked.

The defense team’s answer largely sidestepped the question and did not offer much in the way of specifics, while House managers could only postulate.

But most of the questions appeared aimed at scoring political points, or reinforcing the asker’s own positions on Trump’s guilt.

Democratic Sens. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, Bob Casey of Pennsylvania and Sherrod Brown of Ohio asked, if the Senate acquits Trump, “what message will we be sending to future presidents and Congresses?”

Republicans asked several questions highlighting their view that the trial was unconstitutional, and that it was an effort by Democrats to hurt Trump. In one joint question, several Republicans asked the defense attorneys “isn’t this simply a political show trial” aimed at shaming Trump and the 74 million people who voted for him last November?

“That’s precisely what the 45th president believes this gathering is about,” Castor responded.

By the end of the two-hour question-and-answer session, the House managers and Trump’s attorneys appeared angry and frustrated with the other side. The sessions did not appear to change anyone’s mind, setting up closing arguments and a final vote Saturday that appears likely to result in Trump’s acquittal.