Missing Travel? This ‘Irreverent Guide’ Visits Anthony Bourdain’s Favorite Places

LISTEN

BY NEDA ULABY

The new book World Travel: An Irreverent Guide is credited to Anthony Bourdain. But it was not really written by the bestselling author, chef and TV personality who died in 2018.

World Travel: An Irreverent Guide was assembled by one of Bourdain’s associates, Laurie Woolever, based entirely on his previous writings and an hourlong interview conducted shortly before his death. Bourdain had collaborated with Woolever on 2016’s Appetites: A Cookbook, and this project was conceived of shortly thereafter, she says, with the intent to spotlight some of Bourdain’s favorite places around the globe.

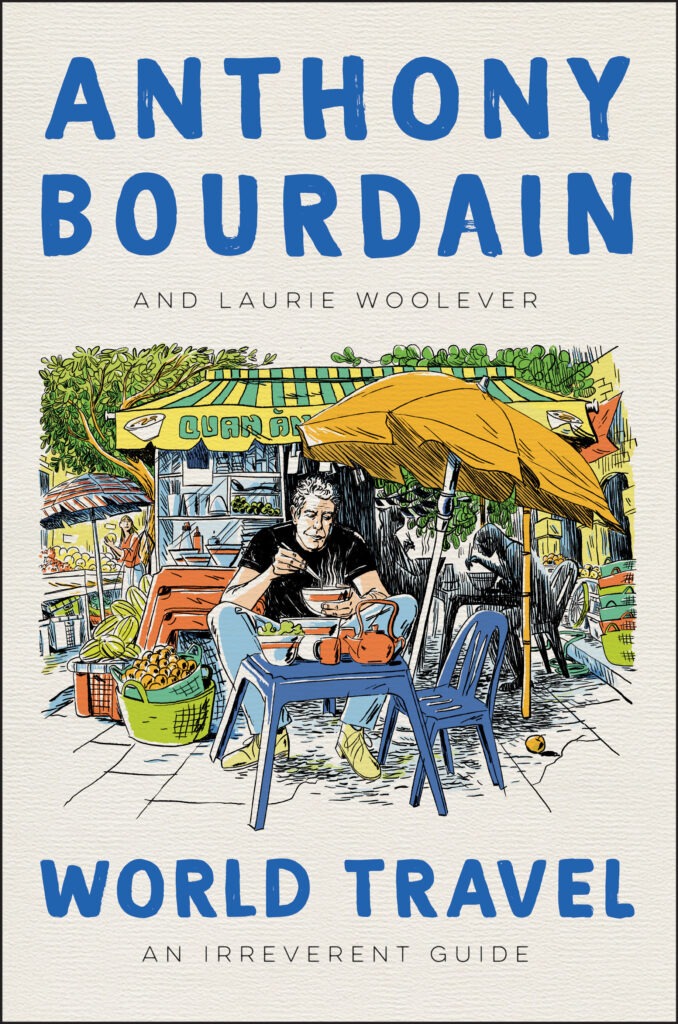

World Travel by Anthony Bourdain and Laurie Woolever

Given the dearth of original writing by Bourdain himself, World Travel contains a handful of tributary essays, by the likes of Bourdain’s brother Christopher, music producer Steve Albini, and Nari Kye, who worked as a production manager on Bourdain’s TV show, No Reservations. She describes, in her essay, how her former boss profoundly changed her life.

“The South Korea episode of No Reservations started as a joke,” she writes. “At the end of Season 1, I said, ‘We’re all going to eat Korean barbecue, and drink lots of soju.’ I got us a huge table in Manhattan’s K-town, and Tony came. We went outside to smoke, and in my drunken soju haze, I said, ‘Tony, you have to swear you’re going to Korea.’ And he said, ‘Of course. And you have to come with me.’ ”

What happened after that drunken conversation was not a joke, Kye says.

“It’s hard not to get emotional when I talk about Tony,” she says, wiping away tears during a Zoom call from her Brooklyn home. Kye explains she was surprised not just to come along for the South Korea episode, which aired in 2006, but also to be its focus, along with her family there.

The show follows Kye and Bourdain as they explore Seoul’s famous Noryangjin fish market, visit a village famous for its kimchee, peer at soldiers guarding the DMZ and drink copiously at a karaoke bar. (Off-camera, Kye says, Bourdain performed a Billy Idol number.) The two sat down with Kye’s grandfather over a bowl of spicy fish stew as part of the episode. He described the trauma of escaping from his home in what’s now North Korea in 1951.

“If I could go back there once before I die,” her grandfather explains in Korean, “I would have no other wish, if I could just see my parents’ graves and just cry my heart out. There’s nothing that can be done, though. That’s just the way it is. That’s my fate.”

Kye and Bourdain listen, rapt. “I might not have learned these things had it not been [for] Tony and the show,” Kye mused to NPR. “I was one person before I made the show. I was a different person afterwards.”

As she recounts in her essay, Kye did not grow up feeling proud of her family’s history or culture.

“I moved to the States when I was 5, from Korea, and after that, I lived in a predominantly white, Anglo-American community,” she writes. “As a kid who already looked different from everyone else, I was trying to fit in as an American and was mortified by my Korean heritage. My mom cooked only Korean food. My parents spoke only Korean to me … We basically lived in Korea in our house in a very American town.”

Laurie Woolever and Anthony Bourdain at the Aqueduct Racetrack in Queens, N.Y.

CREDIT: CNN/Ecco

Before Kye’s friends would come over — “white, blond-haired girls named Jenny and Erin who would wear shoes inside their houses” — she would hide everything in her house that looked Korean. She was a recent college graduate, still in her early 20s, when she traveled to South Korea with Bourdain. His full-throated enthusiasm for Korea’s spectacular history, culture and food transformed her perspective about something she had dismissed and taken for granted — and ignited her own sense of creative potential. Now Kye works on a children’s television show for Korean American families, and she’s writing an autobiographical screenplay, including her travels with Bourdain, filtered through learning about food.

“I didn’t know this had been so important to Nari until after [Bourdain] died, and we were talking about his impact on us,” Laurie Woolever told NPR. “Had Tony lived and written his own essay for the book — which was the original plan — I never would’ve gotten to hear from Nari. And I think it’s important, and I want people to understand how deep [Bourdain’s] legacy is.”

Part of that legacy, says Nari Kye, comes from how Bourdain reflexively stood up for underdogs, his embrace of those who get marginalized. “He always made people feel like they belonged,” she says.

And wherever he traveled, she says, Anthony Bourdain managed to belong as well.