What the ‘Pandora Papers’ show about how the powerful hide money from public view

By Joe Hernandez

A massive investigation from more than 600 journalists across the globe sheds new light into the shadowy world of offshore banking — and the high-powered elites who use the system to their benefit.

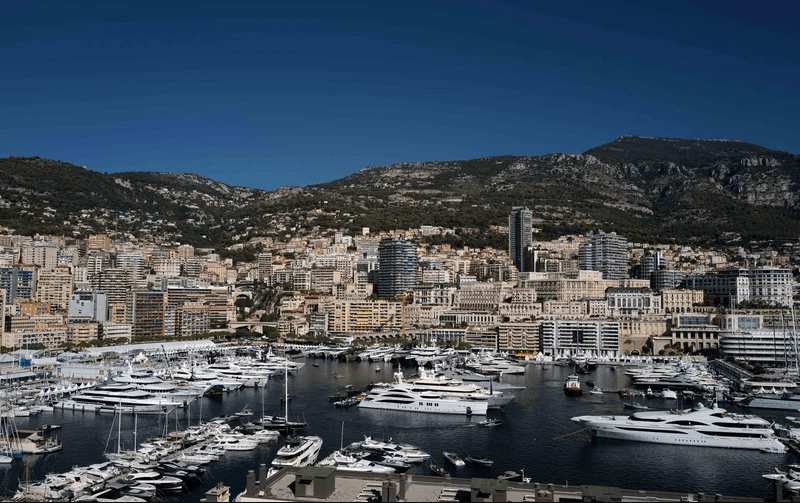

A journalist-led investigation found that a woman had acquired a waterfront property in Monaco after she reportedly had a child with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Here, yachts are seen moored at the Hercules Port in Monaco. CREDIT: Valery Hache/AFP via Getty Images

The exposé, dubbed the “Pandora Papers,” shows how the world’s wealthy hide their money and assets from authorities, their creditors and the public using a network of lawyers and financial institutions that promise secrecy.

It’s built on a trove of 11.9 million records leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which in turn shared them with partner media outlets such as The Washington Post and The Guardian to help conduct the large-scale investigation.

“These are secretive, confidential documents from offshore tax havens and offshore specialists who work to help rich, powerful and sometimes criminal individuals create shell companies or trusts in a way that often helps either obscure assets or in some cases even help avoid paying taxes,” senior ICIJ reporter Will Fitzgibbon told NPR’s Weekend All Things Considered.

The explosive global investigation can be a lot to take in, so we’ve highlighted some major takeaways:

Tax havens are legal, but they can be used for illegal (or unsavory) purposes

According to the authors, the term “offshore banking” was originally coined to refer to island nations with lax finance laws that allowed people to hide their assets.

But now it refers to places outside of a person’s home country where they can shelter their money without having to abide by the rules where they live.

The list includes some places you might not expect. The financial service companies that appear in the Pandora Papers do business in Belize, the British Virgin Islands, Singapore, Cyprus, Switzerland, as well as in U.S. states including South Dakota and Delaware.

Offshore accounts are not necessarily illegal. Many of the companies that responded to the journalists’ requests for comment said they had not broken any laws.

But account holders can use offshore trusts and shell companies for illicit purposes, such as to avoid paying taxes or to fund criminal enterprises.

The leak implicated a lot of world leaders

King Abdullah II, who rules Jordan, spent more than $100 million on lavish properties in the U.S. and Europe while his country fell deeper into political turmoil, The Washington Post reported.

A woman suspected of being in a years-long relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin became the owner of a pricey Monaco apartment, days after reportedly giving birth to his child, the paper also found.

Those were two of more than 300 current and former politicians who appear in the Pandora Papers, the journalists said.

Among them are 14 sitting heads of states, including the Dominican Republic’s President Luis Abinader, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta, the Czech Republic’s Prime Minister Andrej Babis and Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky.

“At a time when politicians routinely stand up on stage and say that they’re committed to accountability, what the Pandora Papers instead shows is that the same people who could, if they wanted to, help overcome secrecy instead are participants in that system,” said Fitzgibbon.

Even after the Panama Papers, offshore banking remains a lucrative industry

When the “Panama Papers” investigation was released five years ago, some thought it would lead to reforms in offshore banking that would make it harder for people to hide their assets.

Instead, the Pandora Papers investigation reveals that the wealthy simply found new ways to stash their cash and avoid scrutiny.

The leaked documents contain details on more than 29,000 offshore bank accounts, over twice the number exposed by the Panama Papers in 2016.

The records show that those involved in offshore banking also worried about — and sought to avoid — another leak of confidential information on the scale of the Panama Papers.

South Dakota is an offshore tax haven? Yep

One of the more surprising findings of the Pandora Papers is the explosive growth of offshore banking inside the U.S.

Specifically, South Dakota and Nevada are among the U.S. states that have “adopted financial secrecy laws that rival those of offshore jurisdictions,” the journalists found.

The documents show that foreign leaders and their family members have used U.S.-based trusts to deposit personal wealth.

Still, many of the country’s richest citizens, such as Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Tesla founder Elon Musk, don’t appear in the Pandora Papers.

The journalists said experts told them that could be because they use offshore financial services firms that were not included in the Pandora Papers leak, or because the ultra-wealthy pay such low tax rates in the U.S. that they feel less of a need to hide their finances abroad.

9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))