In their own words: Rosalie Fish

Read

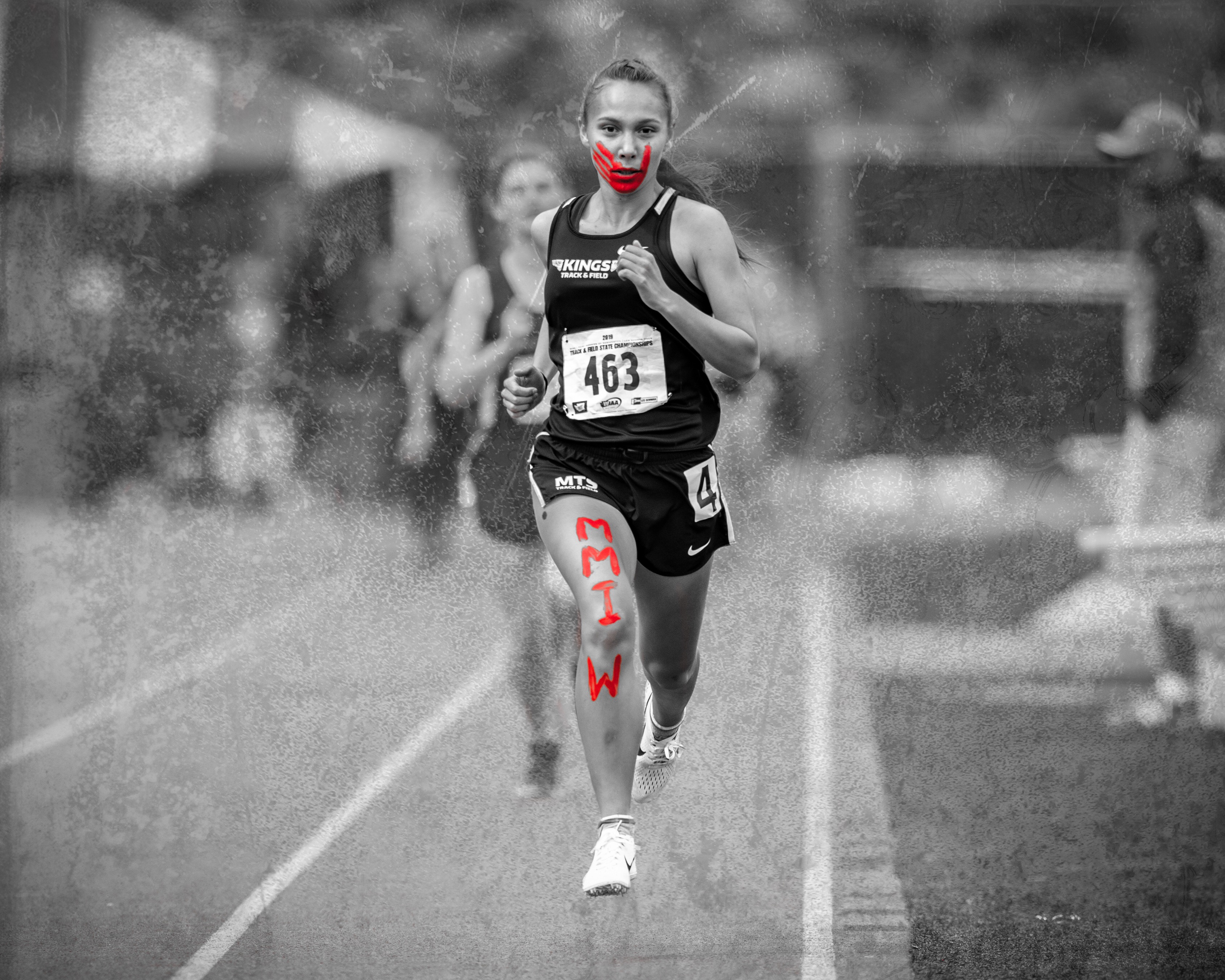

Northwest Public Broadcasting reporters are interviewing Indigenous people throughout the region to learn what they want people to understand about their culture and who they are. Reporter Lauren Gallup spoke with Rosalie Fish, a University of Washington student and athlete, who is using her platform to raise awareness of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis.

“wiʔaac, ʔəsx̌id čəxʷ. Rosalie Fish tsi dsdaʔ. bəqəlšuɫabš čəd. Hi, my name is Rosalie Fish. I just introduced myself in the traditional Lushootseed language of the Coast Salish people. My pronouns are she/her. I’m 21 years old, and I am a social work student at the University of Washington. And I’m from the Cowlitz, Muckleshoot and Yakama tribes,” said Fish.

In high school, Fish became known beyond her tribal communities when she began dedicating her cross country and track races to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis. Fish said it’s important to raise awareness and end the crisis.

She also said representation and self-care are important, especially in the fall.

“I think fall can be kind of a difficult time for some Natives,” Fish said. “We start off with Columbus Day. And then we’ve got Halloween, which can be a little bit infuriating based on sometimes there’s appropriation of Native culture and that fetishization of Native women. Then you’ve got Thanksgiving, which is kind of just a loaded holiday in general.

“I think (it’s important to take) those moments and reclaim these months and these days, like Indigenous Peoples Day and again with Native American Heritage Month. It’s not only a symbol of resilience with Native communities, navigating for ourselves, but it’s also a time to hold nonnative communities accountable. To recognize not only the traumatic history and the oppression that Native people have faced but also use it as a time to be accountable and educate themselves on the diverse tribes around us, the land on which we stand, and how any of us, especially nonnative folks or institutions, wouldn’t be able to do what we’re doing now if not for the Native communities that are from that land [who] continue to fight for the wellbeing for that land, even today,” Fish said.

Fish said the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis is devastatingly pervasive and prolific.

“We face higher rates of violence, more than any other ethnic demographic in the United States. Those rates of violence only compound if you’re a Native girl, if you’re two-spirit, lesbian or bisexual. So that intersectionality is a huge part to violence against Indigenous women.

“Even as an Indigenous girl, the minute you turn 12 years old, your rates of violence increase about 2 1/2 times. We are targeted because of our prominent roles in our community. Indigenous communities are often matriarchal – (women) hold a divine and protective role in our communities. Our femininity is often based with the land and Mother Nature and how we are one with our nature and with our Earth. Violence against the land is violence against women. Especially back in colonization. To take control of the land, they tried to take control of the women,” Fish said.

Washington state has particularly high rates of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, according to a report from the Urban Indian Health Institute, a tribal epidemiology center.

Out of 71 cities surveyed in the report, Seattle has the highest number of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in the nation. Tacoma is tied with Gallup, New Mexico, ranking sixth and seventh in the nation, according to the report.

“We are living this crisis every single day. Our families and our younger siblings are living this crisis,” Fish said.

Fish is fighting to end the violence and care for the people it impacts through studying social work and working with Mother Nation in Seattle, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting Native women in crisis.

“It can be pretty scary (to) put yourself out there like that,” Fish said. “But we are seeing incredible results. We’ve got the Red Alert being established in Washington. We’ve got the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Task Force.”

The Red Alert, which Gov. Jay Inslee signed into law in March, created a first-of-its-kind statewide alert system for missing Indigenous women and people. The alert is similar to Amber and Silver alerts and is meant to give law enforcement more tools to find missing Indigenous people.

Through the state attorney general’s office, the state’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Task Force is assessing the systemic causes of these cases and will produce a report in June.

Working and living this crisis is heavy, Fish said. She said she tries to prioritize taking care of herself.

At this time of year when many nonnative people might be dedicating more time to learning about the tribes within their communities and the lands they live on, Fish said the sole focus shouldn’t be on trauma.

“It is really easy to focus on the hardships that we face as Native people and our traumatizing history, our relationship to systemic oppression, to generational trauma, the mental health issues and violence that we face, and how we’re especially vulnerable to those kinds of things. That we are constantly experiencing grief and loss all year round.

“To acknowledge those hardships and those obstacles, it’s just as important to acknowledge our resilience, our responses to trauma, how we have come together in very strong, connected communities, and how our culture relates to our strengths. To acknowledge that trauma, you have to acknowledge that resilience and look at Native communities not through a lens of pity but through the lens of inspiration. That motivation to take action and make sure that this month is not only a time to educate yourself or to reflect on the atrocities done on Native people, what we continue to face based on historical oppression, and how that has manifested itself into modern-day problems and issues of violence, but seeing Native communities through a lens of strength, resilience.”

This story is part of a series of conversations with Indigenous people throughout the Northwest reflecting on Native American Heritage Month.