New USGS migration maps of Western wildlife might ease pressures from development and roads

Listen

(Runtime 00:50)

Read

Lately, Matthew Kauffman has been thinking a lot about spaghetti – wildlife spaghetti lines, that is.

Kauffman, who works for the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Wyoming as a research wildlife biologist, has been working with more than 30 other tribal and state officials for the last several years to create new maps.

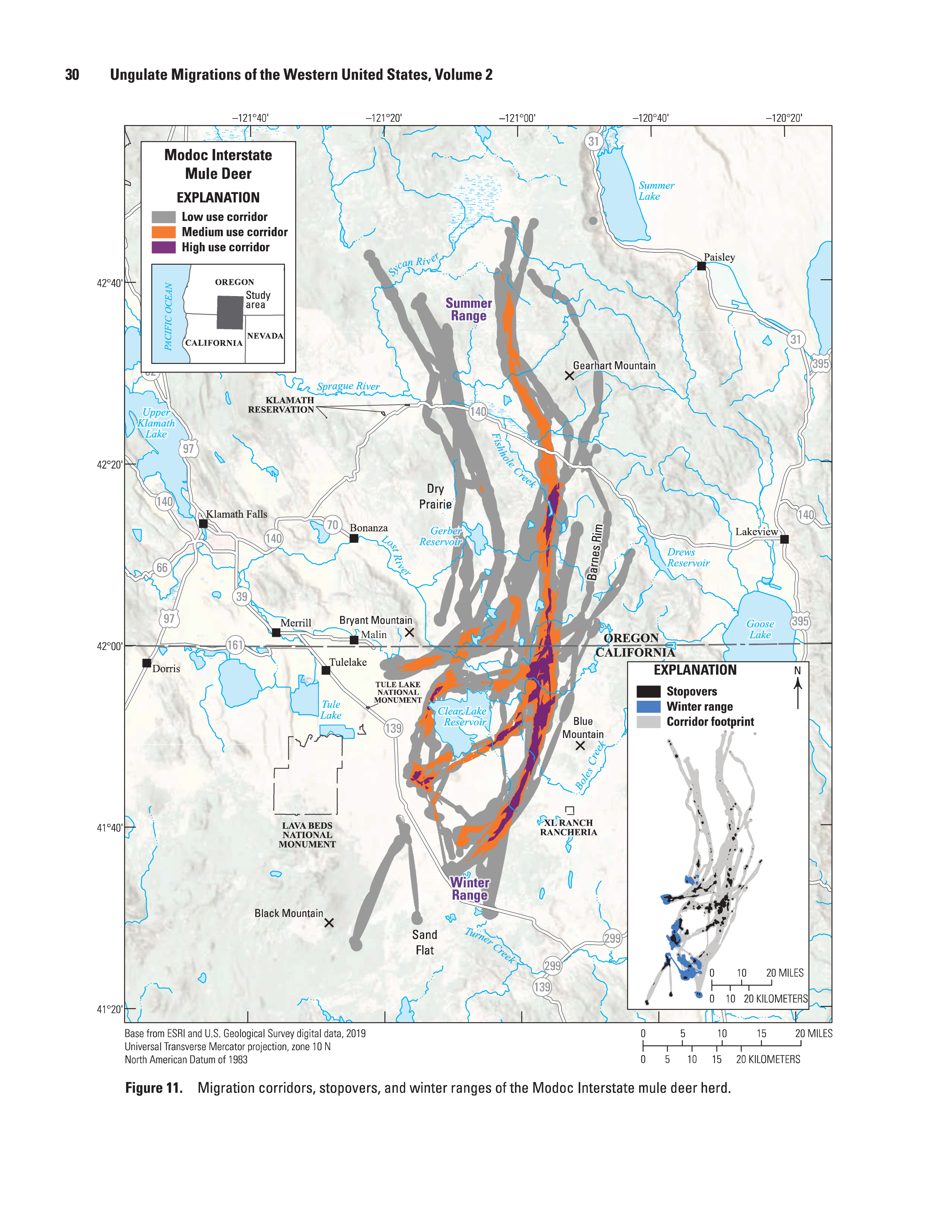

They want to see where deer, elk and pronghorn highways run throughout America’s Western states. And those wandering lines on the map representing individual animal trails — they look a lot like spaghetti. Kauffman says it’s where those trails come together that’s really interesting. USGS recently published an analysis of those intersections in a new report.

“Our task with the analysis is to figure out: what is the population doing? Right? We think of it as sort of like a road system,” Kauffman said. “We are trying to future out what interstates that the migratory ungulates are using that most of the animals are using.”

A mule deer in front of a game fence. Fence lines, highways and development can be difficult for wildlife migrations. (Credit: Joe Riis.)

Kauffman says it’s those wildlife interstates — or high use corridors – that are the most important for the population to keep open and functional.

Kauffman has studied wildlife for 16 years. But he says it’s only recently that scientists have been able to collar a significant number of them across 11 states, to see where they are going en masse.

“We haven’t known where all these migration corridors are precisely,” he said. “And at the same time we’re adding more fences, more roads, more energy developments, more solar, more wind – all of these things that make migration more difficult.”

The new maps show what Kauffman calls, “spaghetti lines” of individual animal trails — and they make darker trails on the group migration routes. Kauffman says it took the cooperative work of many tribes and states several years to collar thousands of animals and retrieve all the transmitters to make the new maps.

Kauffman, who led the research, says many migration routes have already been lost. He says migrating seasonally is the best way for ungulates to make a living in many Western states. He says migrations are often underpinned by national parks, or government lands – but also across working landscapes like timber forests or rangelands. But deer, elk and even buffalo need these narrow corridors to keep making a living in a fragmented West.

“These migrations move across the landscapes where we live and work,” Kauffman said. “And we’re changing these landscapes. That just makes it a much more complicated task to keep the migrations open for what the migratory ungulates need, but also develop the lands for what the humans need. And the maps are the key to doing that.”

A map completed by the USGS shows the ungulate migration paths of mule deer in the Western United States. Individual animals were tracked with collars and when the individuals’ paths overlapped clear pathways could be revealed. (Credit: USGS.)