A park from pollution: 30 years after the ASARCO smokestack demolition, Tacoma’s waterfront transforms

LISTEN

(Runtime 3:57)

Read

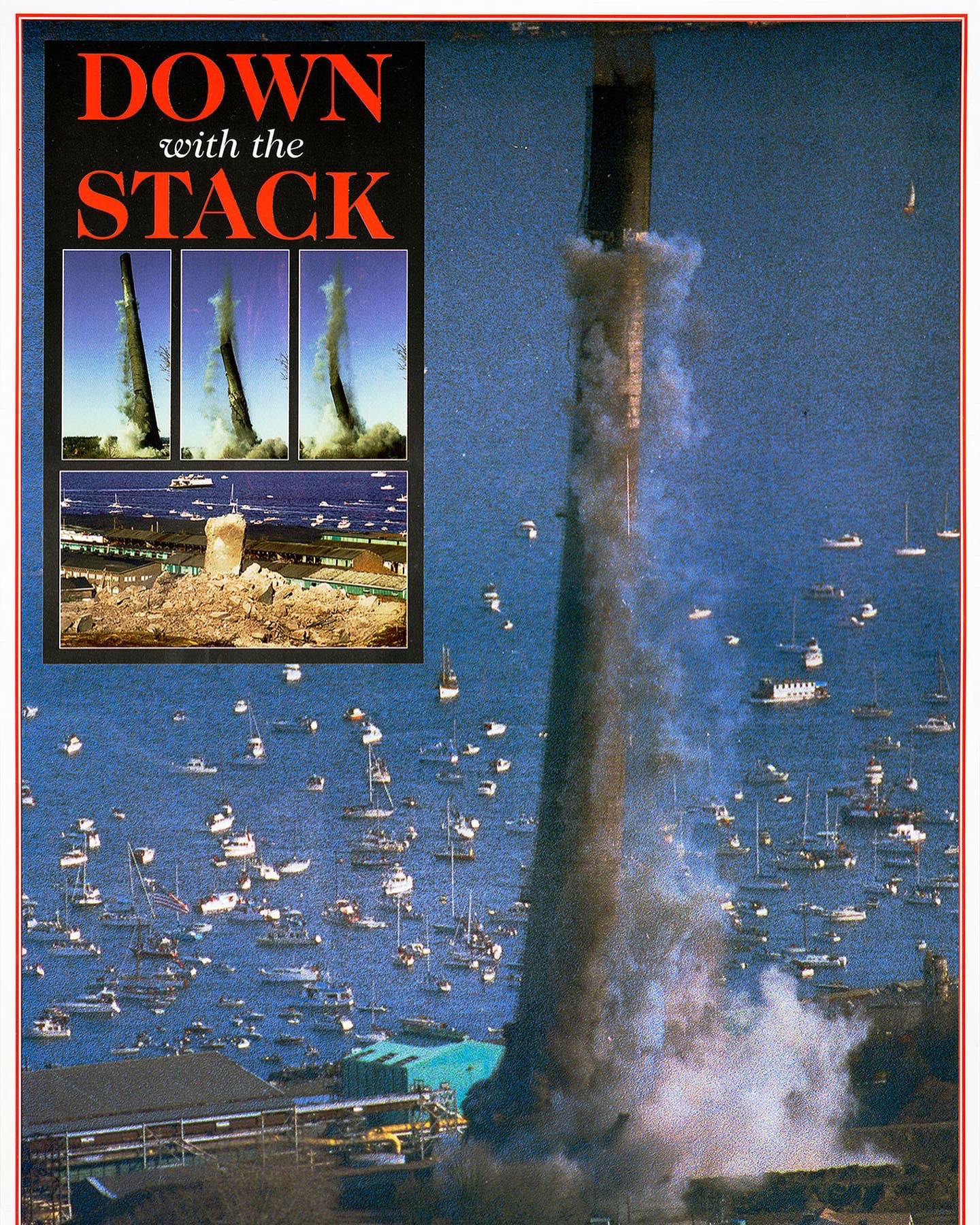

It was a clear day in Tacoma on January 17, 1993. Commencement Bay was crowded with boats. Families gathered on boat decks and across North Tacoma sidewalks to watch the demolition of what was once the tallest smokestack in the world, the ASARCO smokestack that loomed over Tacoma’s waterfront for nearly 100 years.

With the press of a button, a child, supervised by demolition experts, detonated the smokestack. People cheered, bought commemorative sweatshirts and Doug Taylor’s grandfather set off an air horn in celebration, nearly causing his father to topple off their boat.

“It was comedic in a sense, Dad almost falling over because it was so loud. He was shocked by it,” Taylor recalled with a chuckle. “A lot of people were happy to see the smokestack go. And it’s hard to believe it’s been 30 years in a way … but it has.”

For nearly 100 years, clouds of heavy metals, mainly lead and arsenic, billowed out of the smokestack, settling in a plume 1000 square feet around the plant. Over time, the plant dumped eleven acres of toxic slag, a byproduct of smelting copper, into Puget Sound.

So, on that sunny January day, when that tower went toppling, for many Tacomans, it felt like a turning point.

A commemorative poster from the smokestack demolition in 1993. (Courtesy: The Washington State Historical Society.)

“It was a big event in Tacoma,” Taylor said. “It was kind of a marker of perhaps a new beginning of things being cleaner and more of that area opening up on the waterfront, as it has.”

The ASARCO copper smelter closed down in 1985 following a mix of environmental regulations and a recession. Cleanup and transformation of the site ensued, changing the waterfront forever.

Cleanup Begins

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) called for an eight-stage cleanup of the site after the plant shutdown, and structures were demolished. The Washington State Department of Ecology was tasked with cleaning up the massive smelter plume, and educating people about the ongoing risks.

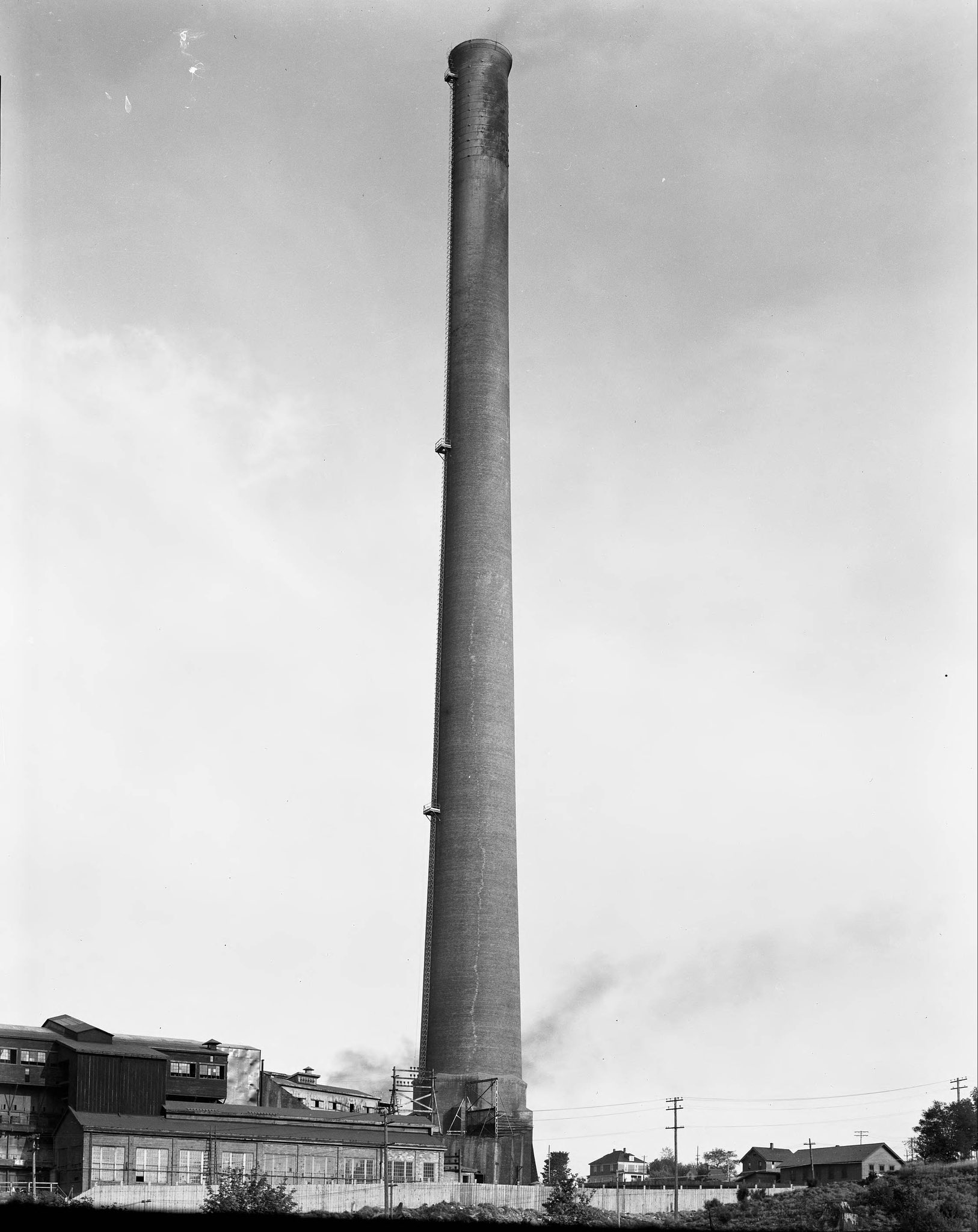

The smokestack in 1935. (Courtesy: The Tacoma Public Library)

The smelter had two previous owners, including William Rust, of the Rust Mansion. He sold it to the American Smelter and Refining and Company (ASARCO) in 1905. ASARCO transitioned the smelter from lead to copper. Heavy metals, like arsenic and lead, emanated from the 571-foot-tall smokestack — and settled into the soil.

Arsenic has been linked to cancer, heart disease and diabetes; and lead exposure can cause permanent cognitive impacts. That’s concerning for everyone, but especially young kids, who are still growing and developing — and like to play in the dirt.

In 2000, the Washington State Department of Ecology created the Tacoma Smelter Plume project, to continue clean up efforts and public safety education.. Marian Abbett is the project manager.

“We’re not going to be able to clean up all of this contamination, it’s just too much, too far spread, we need to manage the risk,” Abbett said.

Cleanup efforts target schools, childcare centers, parks and residential yards.

Abbett said there will always be risks and it’s best to treat the dirt as if it is contaminated — wash hands and pets, don’t wear shoes in the house, garden using raised beds. The department’s Dirt Alert program provides more information on protection.

A majority of King, Pierce and Thurston counties are within the plume. The Department of Ecology created a searchable map where residents can input their address to learn if they live within a contaminated area. The map covers different contaminants statewide, from Tacoma and Everett smelter plumes, to contaminated orchard lands and the upper Columbia River.

ASARCO went bankrupt in 2005, and settled a claim with the State of Washington that included paying a $94.6 million settlement for cleanup of the Tacoma smelter plume, Abbett said.

Pollution to Park

In the process of smelting copper, a waste material known as, “slag” is created. Slag can be used to build up land masses. In 1917, ASARCO began dumping slag into Puget Sound, at the request of the city’s park board. Claire Keller-Scholz, planning and asset management administrator for Metro Parks, said at the time, they wanted to create a breakwater for the marina along the shore, to protect boats from rough storms. While this may sound preposterous now, no one knew then what environmental consequences this would cause, and slag was used all along Ruston Way to build up the road.

Slag from the smelter forming the peninsula. (Credit: Karen Pickett, courtesy of Metro Parks Tacoma.)

Metro Parks owned the eleven acres of slag offshore, so when the ASARCO plant shut down, they began to imagine a park for the man-made peninsula.

Remediation and capping were necessary to make the space safe. The EPA removed structures, and laid down layers of gravel, fabric and clean soil to protect people.

The story of mankind terraforming a toxic landmass and polluting the world around him reminded some sci-fi readers of the 1965 novel, Dune. Hence, the park’s name, “Dune Peninsula,” in honor of Frank Herbert, the novel’s author, who grew up across the water from the ASARCO smelter.

“Why it’s relevant to us is because of that same kind of pollution –the story that unfortunately was a legacy of ASARCO –it had a lasting impact,” Keller-Scholz said. “We were able to transform something toxic into a safe and effective space for residents and regional visitors as well.”

A drone shot of Dune Peninsula now. (Courtesy: Metro Parks Tacoma.)

Visitors can walk along Frank Herbert trail and admire eagles flying above, or seals resting along the breakwater. And Wilson Way Bridge connects the waterfront to Pt. Defiance Park.

“The history of the site is just so compelling,” Adam Kuby said. “And it’s such a classic tale of what happened on urban waterfronts all across the country.”

Kuby is a public artist who helped design the park, including implementing artwork into the space.

The toxic slag which formed the peninsula was created layer upon layer, which Kuby said reminded him of how geological layers form. He said they tried to reflect that in the design of the park.

“We actually made some of those concrete structures for seating and retaining walls by pouring layers of concrete, [so] that you could see the different layers, to kind of reflect the way that the whole site was made,” Kuby said.

Kuby also was commissioned for an art piece in the park. When researching the space and deciding what to construct, he said he was inspired by the smokestack.

“When that smokestack came down … for a lot of people, it seemed like that was kind of the emotional pivot point, and a turning point for how people felt about this place,” Kuby said.

Adam Kuby’s art installation, Alluvion, in Dune Peninsula. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

His piece, Alluvion, represents the smokestack demolition as a starting point: transforming into a field of wildflowers. Pieces of steel across the grass cascade down in various stages of decay, from a tall tower, to pieces, representing the demolition, into a bed of wildflowers, representing the restoration.