‘Native and Strong’ provides culturally-informed crisis support to Washington callers

Listen

(Runtime 3:30)

Read

A new crisis lifeline in Washington is offering mental health support for Native people, by Native people. Operators say it’s making a world of difference for the callers seeking help.

Since its launch in November 2022, Washington’s Native and Strong Lifeline has answered roughly 650 calls. Native people face a higher risk of suicidality than any other racial or ethnic group in the United States — driven by intergenerational trauma, including: forced displacement, land dispossession and assimilation.

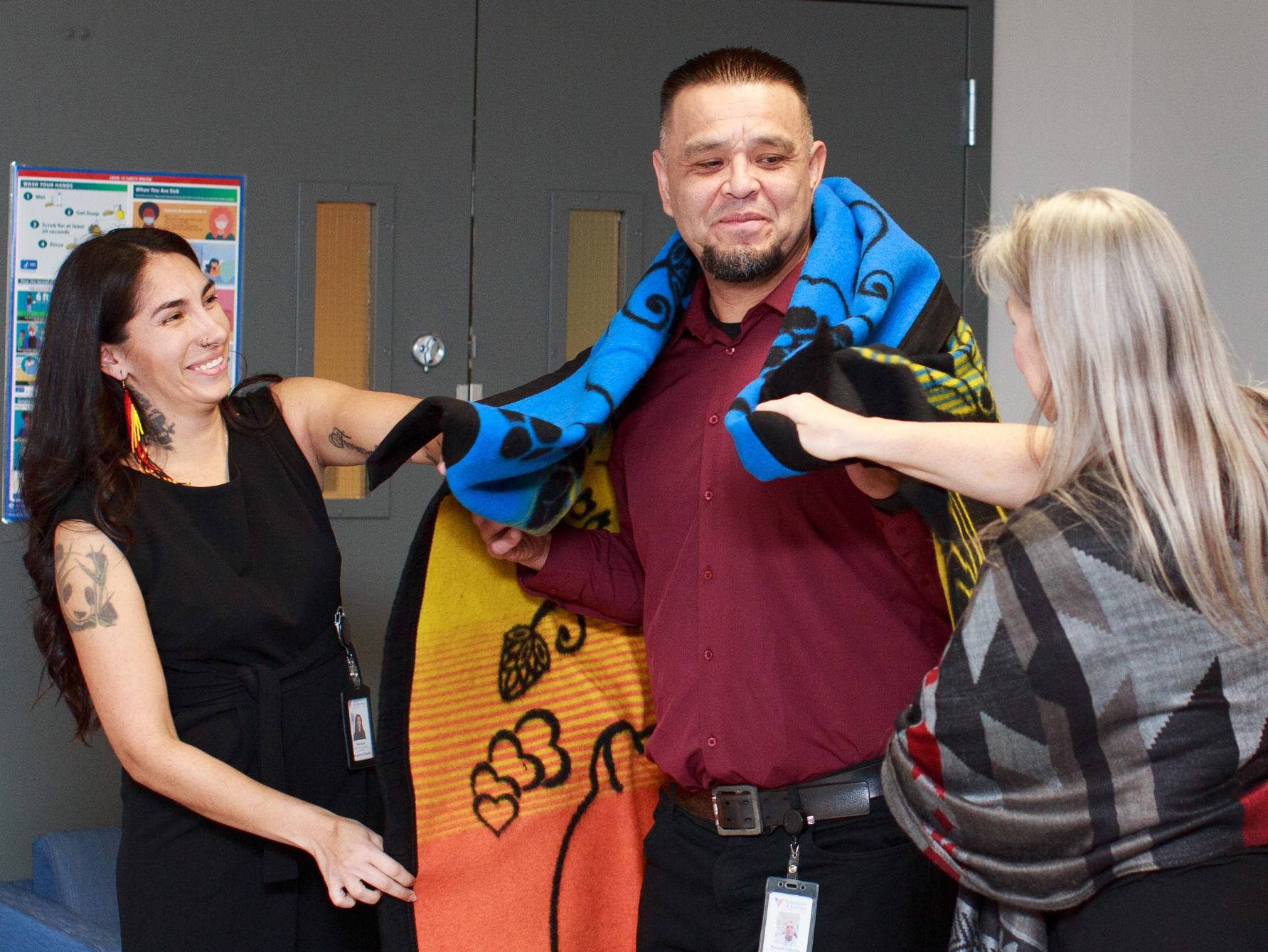

Robert Coberly, a crisis counselor and enrolled member of the Tulalip Tribe, said callers benefit from talking to crisis counselors who already have cultural understanding and experience with generational trauma affecting Native people. It’s something he’s experienced personally when seeking mental health care.

“I’ve had a couple of therapists that were not Native, and it just didn’t work. They didn’t understand, I couldn’t help them understand,” he said. “Having another Native therapist [or] counselor just makes it simpler.”

The Native and Strong Lifeline, an expansion of Washington’s 988 suicide and crisis lifeline, is the fourth option Washington callers can select when dialing 9-8-8 (the others being LGBTQ+ support through the Trevor Project, veterans support and a Spanish-language crisis lifeline.) It’s also the first lifeline of its kind for Native people.

The program currently has 12 full-time crisis counselors. Each counselor is an enrolled member of a tribal nation, or a descendant of Native Americans. All are trained in crisis counseling, with an emphasis on issues facing tribal communities today, including: mental health conditions, substance abuse disorders, intergenerational trauma and community-wide socioeconomic disparities.

Crystal James is another crisis counselor and enrolled member of the Diné, also known as Navajo Nation.

She says Native people often mistrust support services that come from outside of tribal communities, because of long and ongoing mistreatment of Native people.

“That’s why I feel like a lot of us are better equipped to kind of help our tribal communities,” she said. “When we have a tribal crisis counselor on the line speaking to one of our tribal members, they’re more likely to open up and be a little bit more receptive to the help that we’re trying to offer them.”

The lifeline also provides connections to outside resources, such as food banks, gas cards, housing and recovery programs. Counselors even helped a parent who needed support filling out paperwork for their child, Coberly said.

Rosalie Lynd, a crisis counselor and enrolled member of Lummi Nation, said the lifeline also gets return callers.

“I had a moment on the phone call with this person, where they were able to recognize some personal growth and some improvements in their mental health,” Lynd said. “This individual was just really grateful to be able to reach out and connect with clinicians like us who are a part of the culture and the community that they could trust and open up with and find that growth within themselves.”

Often, the crisis counselors can personally relate to the experiences of their callers. Coberly started in his current line of work as a recovery coach, and is himself in recovery from alcohol dependance. He said one of the most meaningful calls he’s answered was with a parent who had lost their daughter.

“I lost my son about three years ago,” Coberly said. “They wanted to know how I was able to deal with it without drinking, without hurting myself. How I was able to show up for my family, my daughter, [and] show up in my own life.”

Counselors sharing their own stories can often help break down barriers, Coberly said, especially for callers who might never have been willing to talk about their struggles with non-Native counselors.

“That was ingrained to me, growing up: not being able to trust non-tribal members because of our past, what we endured,” he said. “[I] try to break that barrier down. It’s OK to talk about our feelings and thoughts, and to be able to walk through them, and be in them.”

James said her cultural understanding of Native people and their ways of knowing also helps her connect on a deeper level with callers, and can inform the plan she makes with them about what steps callers take after the call.

“I’ve had one individual cry, and they were like, ‘Oh, my God, I can’t believe I actually got to speak to another Native American who understands me,’” she said. “In that conversation, we did discuss holistic-type methods to use for the individual. We did speak about going into a sweat lodge, we started talking about burning cedar […] For them, it meant the world. And for me as well. Just to be able to connect to them and just speak about things like that.”

This report was made in partnership with Northwest Public Broadcasting, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.