New federal funds will boost broadband expansion in Washington, Idaho

Listen

(Runtime 3:53)

Read

Reporting by Lauren Gallup and Lauren Paterson

Internet inequality across the country has spurred the Biden administration to invest in “Internet for All” programs through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Across Washington and Idaho, service is spotty, spendy or slow. Residents and local officials are making do while the wheel of bureaucracy grinds along.

Where access is lacking, costly or slow

Out on the northwestern tip of Washington, Neah Bay has been home to the Makah Tribe since time immemorial. It’s a one-road in, one-road out town. In 2021, flooding cut that highway off from the rest of the state.

Neah Bay is a coastal region of the Makah Reservation located south of British Columbia. (Credit: Chairman Timothy Greene)

So, getting high-speed broadband access to residents has been a push, but a priority for the tribe, said Chairman Timothy Greene.

“What really pushed us into this area was our educational system,” Greene said.

When all state testing for public schools went online, the tribe’s outdated digital subscriber line, DSL, system couldn’t support the students logging on to test while others in the school system used the internet.

“What would have to happen for one class [of] maybe 12 to 16 kids or so to take to take a test online to meet the state requirements: we would have to [get] everyone in our whole K-12 school — every student, every teacher, every worker — would have to log off the system and not use it,” Greene said. “So those 12 to 15 kids could take a test.”

It was a huge productivity drain.

So, Greene said, they prioritized getting internet connection to the schools. They’ve been working on getting the whole community connected over the past decade. But that takes time and money, so Greene said across the tribe, service is still inadequate. It was just last fall that his own home got connected to broadband.

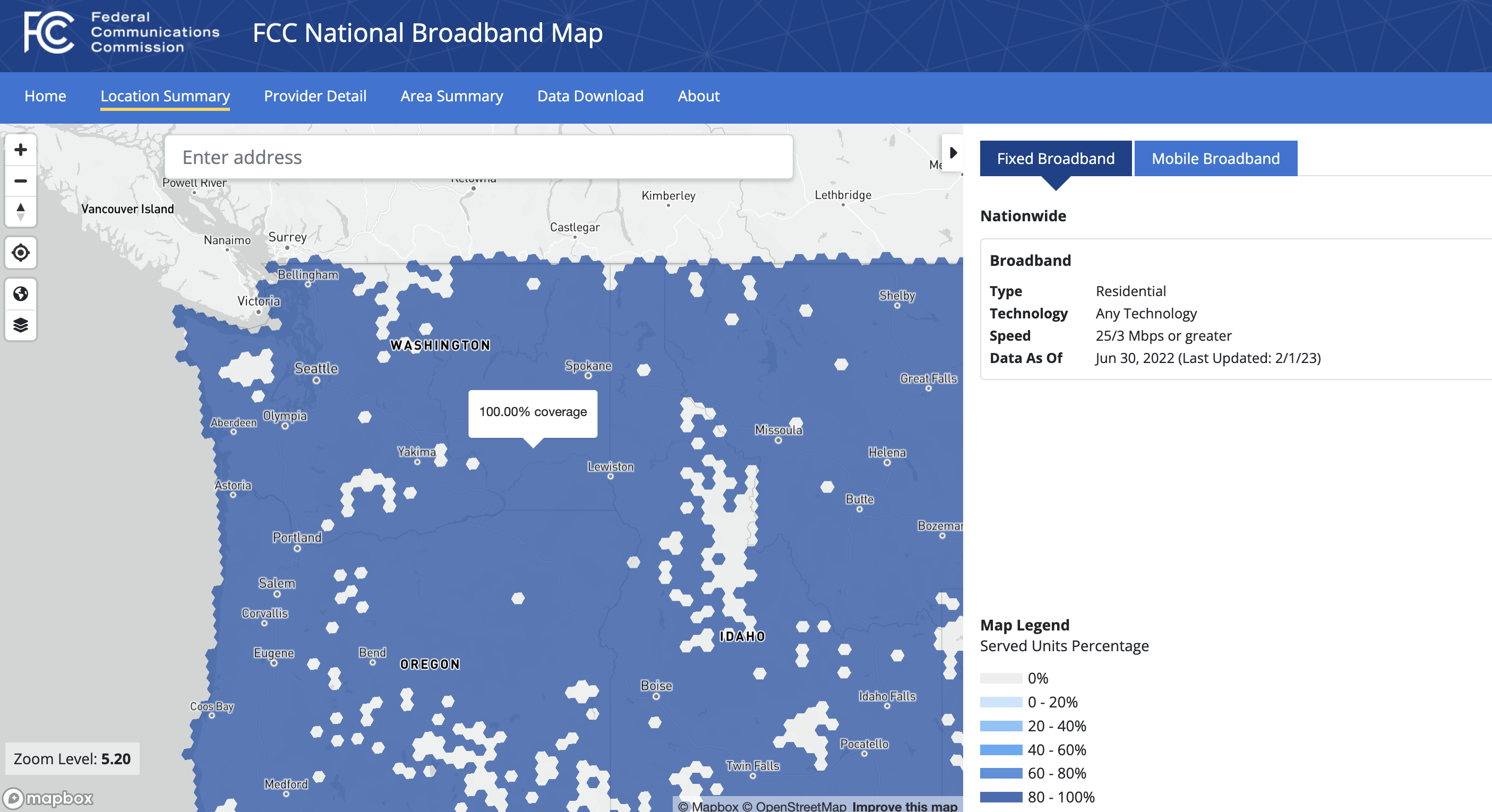

Yet, the Federal Communications Commission’s (FCC) mapping of internet connectivity makes it look like nearly all of Washington, including Neah Bay, is connected. But that’s not true.

The FCC Map currently shows most of Washington state has access to broadband. (Credit: FCC website)

“The way they do it is they take every zip code, and if there’s just one home in the entire zip code that has some sort of internet, even if it’s not great, they consider that to be reliable for the entire zip code,” said Nate Nehring, Snohomish County Council member for District One. “So it shows all of our state is reliable. Of course, that’s not the case.”

It’s certainly not the case in Snohomish County, where Nehring has been a council member since 2017.

“When a lot of people think about Snohomish County, maybe [they] think about an urban county, but we have some pretty significant rural areas, particularly in the northern and eastern parts of the county, which do not have reliable broadband infrastructure,” Nehring said.

Even in Nehring’s district, which is considered to be a fairly urban area, there’s places where there’s no service, even near businesses. And even when there is service, it can be unaffordable for some families.

“If you live in one of these pockets with little to no reliability, then that makes it all the more difficult for you to do your schoolwork or your job,” Nehring said.

Marvin Hume lives in a bit of a slow pocket of rural Pierce County, where he’s lived for 44 years.

“We live in a strange place where we’re kind of cut off from everything,” Hume said. “Because on the west side of where we live is Fort Lewis. So there’s no infrastructure out there. And then north of us there’s also a section of Fort Lewis that goes out and around. So we’re kind of in a little corner where there’s not a lot of people.”

While Hume has internet, it certainly can’t be described as high speed — his connection speed is 12 megabits per second (mbps) with CenturyLink. The definition of high speed internet is a minimum of 25 mbps.

Hume said CenturyLink was going to establish a connection for faster service, but the cable box connection is over a mile away, and the wiring is so old that it won’t support high speed internet.

“We’re just kind of stuck here with what we have,” Hume said.

In the area Hume lives, there’s only about 40 residences nearby, so there’s little incentive for internet providers to build out more infrastructure.

Over in the Idaho panhandle, Engineer Brian Hanson works remotely. He recently bought a patch of three acres at the base of Schweitzer Mountain outside Sandpoint.

“I am relocating my Starlink satellite dish from the roof of my house to the side of my house. There’s a peek up here where it will give me a good clear shot of the sky. So, I can hopefully have better connection to more satellites,” he said.

To work remotely in the woods, Hanson needs internet and there are few options in this remote area.

But more options are on the way.

“What we are doing as part of the [federal programs] is ensuring that every single home and business in the United States and the six territories has access to a high quality, affordable, reliable internet connection,” said Evan Feinman, director of the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program for the National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

Rather than a top-down approach where people in Washington D.C. tell the states what they need, Feinman says this time, the first move in funding is sending all 50 states, D.C. and Puerto Rico initial funds to help them develop a plan to build high-speed internet infrastructure.

Feinman says the federal programs prioritize people who were not well served by prior internet expansion efforts..

“That means rural folks, that means poor folks, that means marginalized communities. And it also means when we build infrastructure, we want to ensure that we start with the folks who don’t have the ability to get online,” said Feinman.

Local governments making it happen

Snohomish County is already preparing for broadband expansion.

Nehring is on Snohomish County’s Broadband Action Team, with the goal of bringing fast, reliable internet access to every home and business in the county. That team organized so they can prepare to receive the money doled out from the state once Washington receives its share of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act funding.

Buried power lines in Parkland, Washington. More infrastructure will need to be built in the Northwest ahead of broadband expansion. (Credit: Lauren Gallup / NWPB)

Nehring said one of the hardest lifts connecting rural homes to internet is the final mile – connecting the service to residences rather than just the nearest road. Using some of the money the county received through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), Nehring said they’re prioritizing that final mile.

“We set aside, as a county council, $10 million of that [ARPA funding] specifically for broadband, with the hope of targeting those last mile areas to see if we can fill some of the gaps which are existing, that maybe some of these other grants might not address,” Nehring said.

That’s also a priority of Pierce County, which hired two private companies to map existing internet service gaps. The companies identified five areas to prioritize funding to fix service gaps. Jon Baker, broadband program coordinator for Pierce County, said the county is working to connect with different internet service providers to expand coverage in those areas using ARPA funding.

It can cost up to $10,000 for homeowners to connect that final mile, Baker said. The county connected all the residents through the Affordable Connectivity Program, which limits how much residents can be charged for the internet. Households can get a discount of up to $30 per month, and $75 on qualifying tribal lands.

Washingtonians can also test their internet speed through the Washington State Department of Commerce website to help the state identify gaps.

Not all broadband expansion programs meet federal program funding requirements. Idaho State Broadband Program Manager Ramón Hobdey-Sanchez says that’s why the state set aside funds for projects that are ineligible for federal funding.

Hobdey-Sanchez says despite receiving $35 million in state funding from the Idaho General Fund, there are requests totaling more than $350 million across the gem state.

“There’s a very significant need. And many of those projects were in North-Central Idaho, and north all the way up into Benewah County,” he said.

Hobdey-Sanchez said his office is also working with tribal governments in Idaho to get federal funding for broadband expansion on reservations throughout the state.

“I’m happy to report we’ve already established great working relationships with the Coeur d’Alene Tribe, the Nez Perce Tribe … The Shoshone-Bannock Tribe over in Fort Hall just recently appointed someone as a broadband liaison and program manager,” said Hobdey-Sanchez.

Next steps for federal dollars coming this way

Washington state is in the early stages of preparing for federal funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Last June, Gov. Jay Inslee requested $500,000 for initial planning funding.

The state began the planning phase of the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program’s five-year action plan this January, which it has to complete to receive funding.

Natasha Langer of the state’s broadband office said the draft plan should be ready by mid-summer.

Over the course of the year, BEAD Program Director Feinman said the states and territories are developing their plans. The information learned from talking to communities and identifying gaps in broadband access will inform and update the FCC map of where internet coverage exists in the U.S., and where it’s still needed.

Choosing not to solve the problem of low income and rural communities lacking access to broadband is an ethical failing, and one where disconnected people pay the price, said Feinman. “Kids [lacking access] have lower grade point averages, [and] are less likely to pursue post-secondary education. Old folks are not able to age in place as safely, and they are not able to do so as long. And the ability to access telehealth telepsychiatry is a tremendously important thing for communities and members of rural communities to be able to continue to safely live their lives and thrive.”

Back in North Idaho, Hanson successfully relocated his Starlink satellite dish. He said the new speeds are now high enough that he can even play virtual reality games without issue, and not lose connection during his work meetings on Zoom.

Hanson grew up in a small town on the Nez Perce Reservation. He said he’s glad to see more rural internet options in his home state.

“I think it’s great. I think it’s giving people an opportunity to work out in the place that they want to live. The only options in the past was to have to go to a big city to have high speed internet, as we grew up on dial-up,” he said. “So for us to now have high speed internet out in the woods, it’s kind of a dream come true.”

Funds for both Washington and Idaho will be allocated by June 30. Approved state broadband projects are likely to begin in the first half of 2024.