Fighting fire with fire: Bringing prescribed burns back to Washington state

Watch

Read

By Lauren Gallup and Mary Ellen Pitney

As the days get hotter and warmer, many Washingtonians are gearing up for the wildfires that will ignite across the region this year, causing smoky skies, evacuations and potentially devastating loss.

Years-long droughts in the West dried out grasses, leaves and dead wood that is now ready to go up in flames with just a spark. As the temperature continues to rise, the air is getting warmer and can hold more water, boosting the chance of thunderstorms. Even during a drought, torrential rainfall can occur during a powerful thunderstorm. The influx of this water helps plants grow, but also increases the biomass that could fuel fires when plants eventually dry out. If lightning strikes the earth during a dry thunderstorm, a fire can explode out of control.

But land managers across the state have been preparing for these summer flames since the fall.

In October 2022, the Kalispel Tribe conducted a prescribed burn in the grassy floodplain of the Pend Oreille River, a tributary of the Columbia River that stretches along the northern Washington-Idaho border with Canada.

The tribe has used fire since time immemorial to manage its landscape, said Ray Entz, director of wildlife and terrestrial resources for the Kalispel Tribe’s Natural Resources Department.

“Fire history for the Kalispel Tribe is one that’s sort of embedded deeply in our traditional, cultural knowledge,” Entz said.

Last autumn’s prescribed burn was done to reduce competing vegetation on the landscape and the risk of fire ripping across the area.

Some species across the Pacific Northwest rely on fire for life; fire allows some plants to germinate and create the right soil chemistry for others to take root. Many tribes throughout the region have long practiced fire stewardship.

“We utilized fire for rejuvenating our first foods — Camus, Indian potatoes, huckleberries — all need that disturbance from fire to rejuvenate themselves and keep growing in sufficient numbers,” said Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation Chairman Jarred-Michael Erickson.

The Makah Ozette is the oldest variety of potato grown in the Pacific Northwest. This potato was only found in Makah gardens until the 1980s. These gardens were managed with fire, along with other techniques. (Courtesy: Irish Eyes Garden Seeds)

By setting regular, controlled fires, tribes were able to maintain an ideal landscape for growing and collecting first foods, clearing land for travel, and preventing more intense, severe fires. During the cooler months of the year, Erickson said tribes now living on the Colville reservation would create small burns to reduce the amount of timber and biomass in the forest.

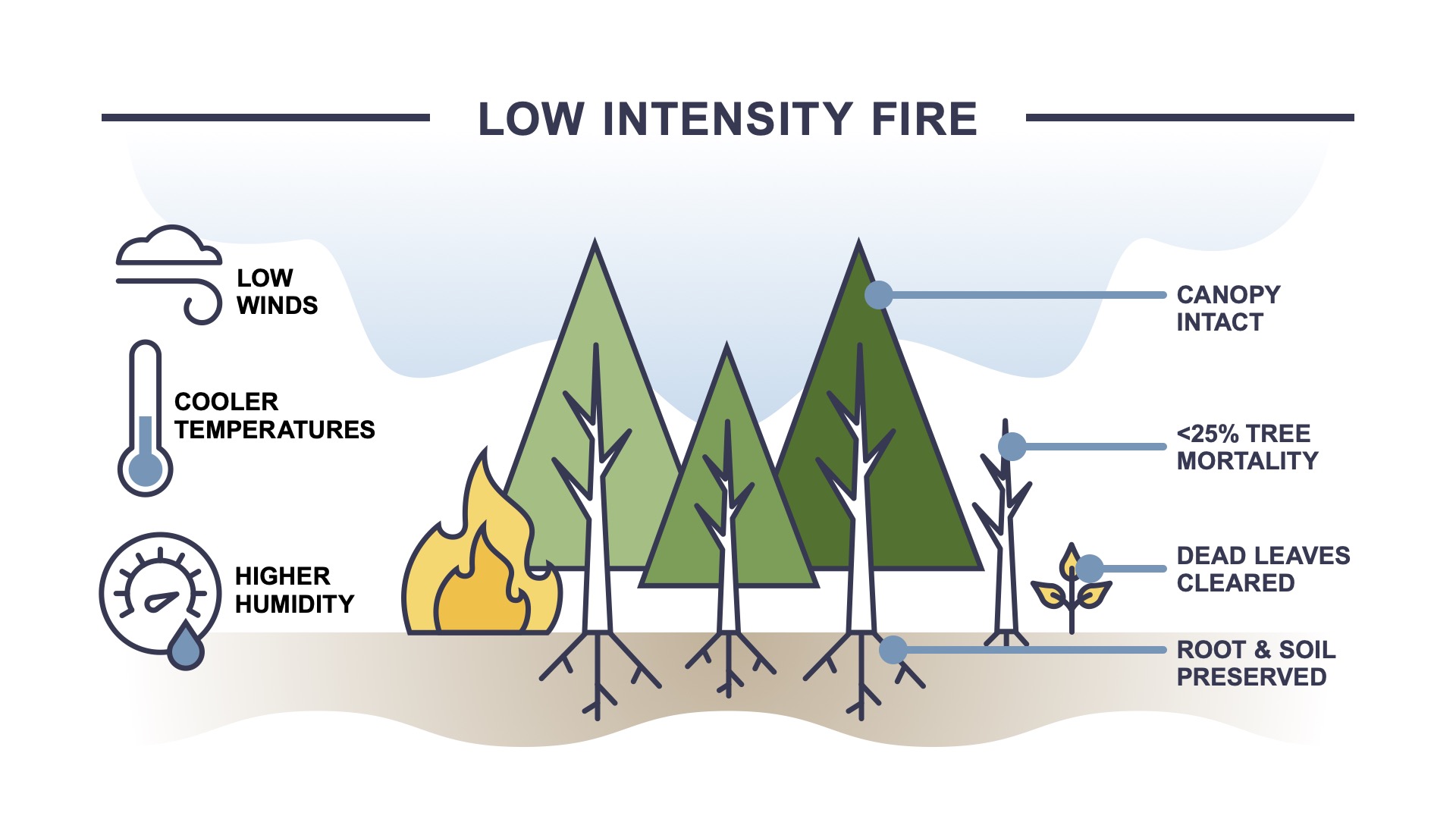

Low-intensity fires can rid the landscape of dry biomass that fuel unplanned fires and allow fires to build into bigger, uncontrolled burns. (Graphic: Kate Fox-Amato)

This reduces the fuel loads for wildland fires that start in the hotter, drier months of the year. So, when fire season begins, a lightning strike won’t start a fire that could decimate timber and food supplies, and risk human and animal life.

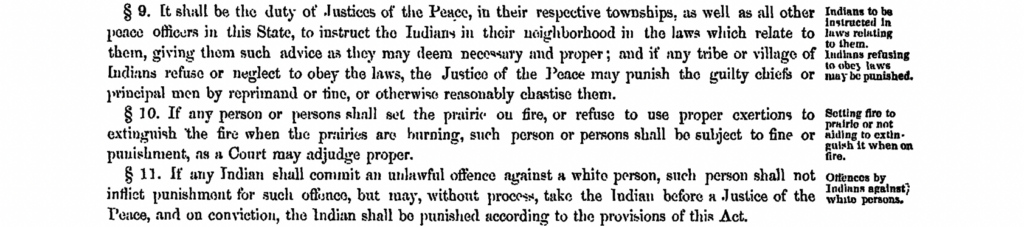

But the Indigenous practice of controlled burns was curtailed by the arrival of white settlers to the region. In 1850, prescribed burns were banned by the “Act for the Government and Protection of Indians,” effectively making the practice a criminal offense. While the act was later repealed in its entirety, the practice was still suppressed in the West.

“An Act for the Government and Protection of Indians.” Section 10 reads: “If any person or persons shall set prairie on fire, or refuse to use proper exertions to extinguish the fire when the prairies are burning, such person or persons shall be subject to fines or punishment, as a Court may adjudge proper.” (Courtesy: American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California)

Historic fires that decimated communities, such as the Big Blowup in 1910, which burned across Montana, Idaho and Washington, led to decades of all-out fire suppression.

“For the longest time the goal was to really try to keep fire out of our landscapes. So, what’s happened is those landscapes have become overgrown with mature forest, with mature vegetation that just keeps [getting] more and more dense,” said Dennis Becker, dean and professor of Natural Resource Policy at the University of Idaho.

Decades of fire suppression, along with a warming climate, only intensified wildfires. In 2015, following an abnormally hot June, Washington saw the largest wildfire season in state history when over a million acres burned. The second largest fire season took place in 2020, when fires burned over 800,000 acres before another 484,000 acres burned in 2021.

Satellite image of Washington state on August 22, 2015. Smoke from multiple wildfires blankets the region. (Courtesy: NASA)

Now, land managers across the Northwest are bringing fire back to the landscape.

2022 was the first time in 16 years that Washington conducted prescribed burns on public lands. The restoration of such a technique reflects a shift in thinking as land managers recognize fire as a cornerstone of the Northwest ecosystem.

The Washington State Department of Natural Resources oversaw the reinstatement of prescribed burns on public lands. Washington Public Lands Commissioner Hilary Franz said without these fires, forests became more dense and must compete for resources, creating unhealthy forests.

“What we didn’t realize is when that happened, now you’re going to take away sort of what nature knew instinctively needed to happen so that the forest could get healthier,” Franz said.

Overcrowded forests suffocate trees, transforming their dead wood full of resin and stripped of water into giant matchsticks.

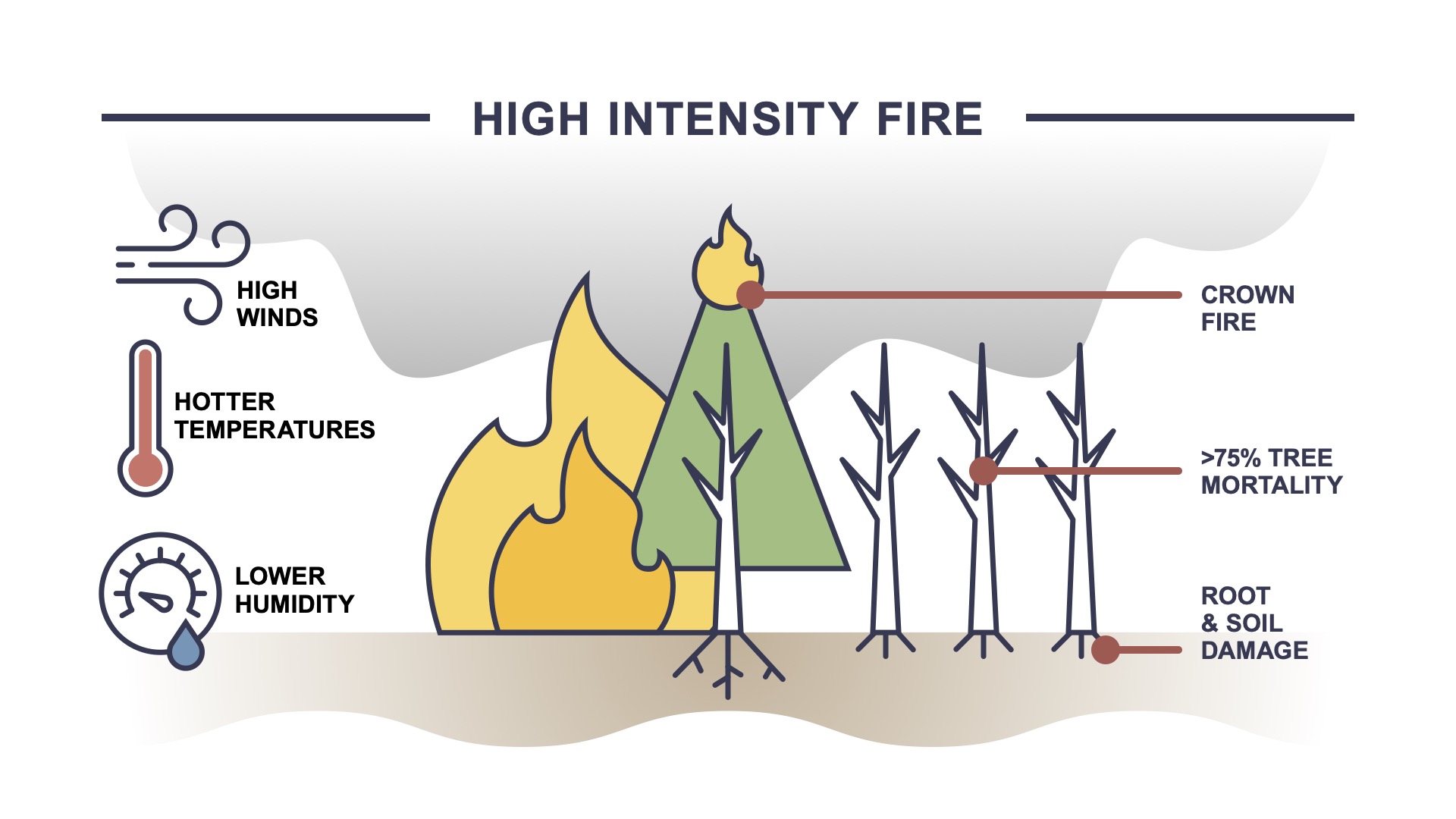

Fires that burn at a high intensity can scarify the soil, making it hard for plants to reroot and grow. That, in turn, can create the perfect conditions for floods. (Graphic: Kate Fox-Amato)

Washington saw those consequences in 2015, when one million acres burned statewide.

“The big lesson is that our forests truly know what they need, not only from the past, but they actually know what they need given climate, and it’s allowing fire to do what fire does in the forests naturally,” Franz said.

Land managers are looking to ramp up controlled burns to restore forest health and clear understories and grasslands to prevent mega fires. Right now, the Colville Tribes burn about 6,000 acres on their reservation every year.

“We should probably be burning maybe closer to 30,000 acres a year for our reservation,” Chairman Erickson said.

And now, some private forest land managers are taking note. Patti Playfair, a third-generation forester managing her family’s Rafter 7 Ranch in Chewelah, Wash., has instituted the practice to protect her family’s timber assets.

“One of the things that fire would naturally do in here is come through at a low intensity and burn off all of these needles and a lot of the pine cones and these branches, and also take out a lot of the small-diameter trees that have come up in the understory,” Playfair said.

A cross-section of a fallen larch tree on Rafter 7 Ranch in Chewelah. Patti Playfair said the jagged cut in the tree shows how often fire burned in the forest, about every 11 to 26 years, not burning hot enough to kill this larch tree. (Credit: Greg Mills / NWPB

But, land managers acknowledge that burning the forest in the right way is a delicate process. Franz said that just because land managers know some forests need some fire does not mean all wildfire fighting should cease.

“What we’re trying to do is say, ‘We made a mistake 50+ years ago,’ we can’t automatically go to, ‘Hey, we’re going to not suppress fires anymore,’” Franz said. “We have to come in with the tools to get that forest back to what it would have looked like if we had allowed fire to do what it needed to do over the last 50+ years.”

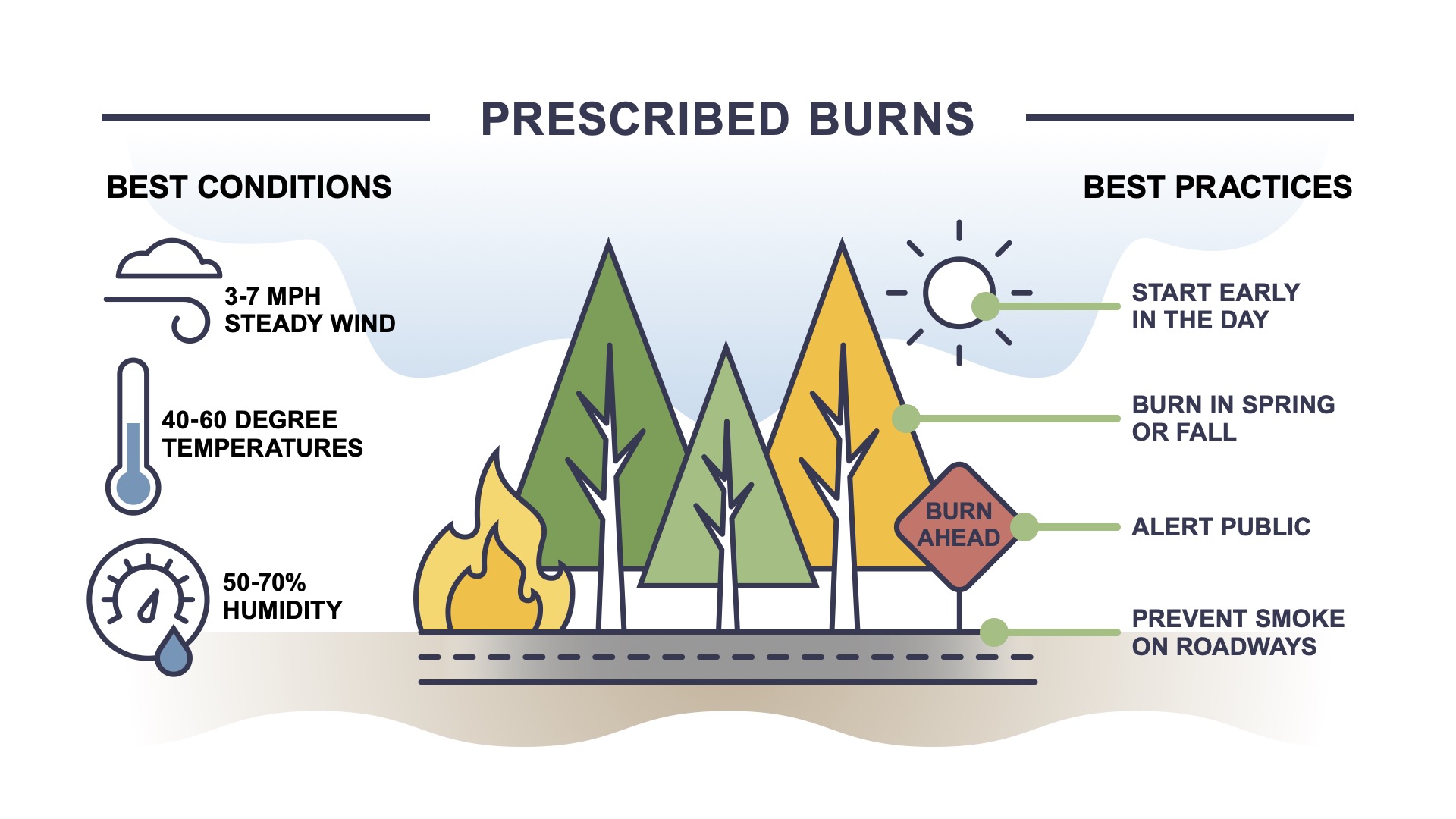

Conducting burns is predicated on the weather, time of year and the landscape itself.

Trained teams create a burn plan to prescribe what the landscape needs and when they’ll be able to burn.

“It’s sort of like a prescription the doctor would write for you, right? And says, ‘What’s the medicine we need for this landscape? What’s the right parameters that will allow us to burn?’” said Kara Karboski, Prescribed Fire Training Exchanges (TREX) coordinator with the Washington Resource Conservation and Development Council.

Trained teams plan out prescribed burns based on weather conditions, what the landscape needs and what the goal of the burn is. (Graphic: Kate Fox-Amato)

This is done well in advance of the actual burn, and can shift with weather conditions.

“We watch it and see if it’s doing what we want it to do, and after that point we can say, ‘No, it’s actually not, even with these parameters, it’s not enough.’ And we say, ‘We’re not going to meet what we’re trying to do out here.’ And we put it out,” Karboski said.

Crews use drip torches to create what’s called a “firebreak” around the perimeter. This helps control the fire by separating the prescribed area from other fuels. Once the fire has burned designated areas, teams extinguish residual hotspots and clean up begins.

But sometimes, these burns don’t go according to plan. In April 2022, a United States Forest Service prescribed burn in New Mexico spun out of control and joined an improperly extinguished Forest Service burn pile. The two fires merged into the Calf Canyon/Hermit’s Peak Fire, burning a collective 341,471 acres from April to June, the largest and most destructive wildfire in New Mexico’s history.

Escapes like this are rare, but they can have devastating consequences. Still, many believe prescribed burns are an important management tool to prevent large, out-of-control wildfires, especially as climate change brings hotter and drier weather.

“It’s going to be increasingly important as we move into a climate that’s not as forgiving as our previous climate was,” Entz said. “Not knowing what’s going to happen, I think we can see the things, the signs in the forest, the vegetative community, that tell us that fire resiliency is going to be more important in the future,” Entz said.