Bringing Indigenous languages into public schools

Listen

(Runtime 3:52)

Read

A number of Washington state public schools are partnering with tribes to bring Indigenous languages into classrooms in an effort to rectify the marred history of Native American boarding schools.

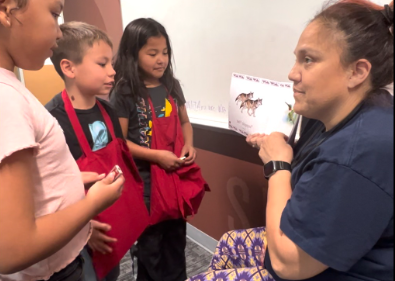

Rachael Barger is a teacher on special assignment with Bethel School District, one of the districts partnering with the Nisqually Tribe to bring its Southern Lushootseed language into the classroom for a small subset of students.

5% of Bethel’s student population identifies as American Indian, Alaskan Native, two or more races or Hispanic and Native. Barger serves over 200 Title VI Indian Education Program students for the district. Title VI is a federal program that aims to meet the specific needs of Native American students.

The tribe and district have partnered, so far, to bring the language classes to two elementary schools for students who qualify for Title VI. Bethel School District had 461 qualifying students this last school year, which is around 2% of its student population.

Barger said those students were excited to learn the language because it felt unique to them.

“It’s something almost like they feel like celebrity status, because it’s now just something that they own,” Barger said. “So that’s been really neat to see them build confidence in that.”

Together with the tribe, Barger said she hopes the district can expand the program beyond Title VI, perhaps as an after-school program offered to older students.

The tribe’s partnership with the Bethel schools is part of the Nisqually Language Resource Center which started two years ago.

“It makes — it chokes me up,” said Catalina Sanchez, research coordinator for the center. “It’s just something new that we’ve always needed in our community. So I’m proud of us for finally getting our own program in our schools and in our community.”

The language work being undertaken by the tribe is part of broader efforts to expand and uplift culture and identity for the tribe.

“You’re starting to see everything kind of awakening right now here in Nisqually,” said Willie Frank III, chairman of the Nisqually Tribe. “You’re seeing everything kind of come together for the tribes, and it all weaves together.”

Frank said he thinks it’s a perfect time to focus again on the tribe’s cultural traditions.

“What I was taught was to tell our story, and, you know, keep building our people up,” Frank said, “and that’s what we’re doing with all this great work in here. I think about the art, the culture and the language; that’s going to be something that sustains us.”

In Ferndale, teachers have been bringing the Lummi language to classrooms since the 1990s.

Smak’ i’ ya is a contracted language teacher from the Lummi Tribe with the Ferndale School District. He has been teaching there since 2001. It was students who first requested the schools offer the language as part of their public education in that district, Smak’ i’ ya said.

Smak’ i’ ya said in the over 20 years that the program has been offered it has made a big impact on the students.

“I guess the big thing is identity,” Smak’ i’ ya said. “Having a place within the public school where you feel comfortable, and you can go, you can be yourself.”

Having the language in the schools, Smak i’ ya’ said, is a way to bring the language back.

When boarding schools punished Native children for speaking their languages, many of those languages were not passed on to future generations. Having these programs in public schools is a way to broaden the reach of Native languages, Smak’ i’ ya said.

“The important thing, if I was to tell somebody, is to have a class, show it to the community, not just the tribal community, but to the community in general,” Smak’ i’ ya said.