Local control, better recognition of tribal police could solve more MMIP cases

Listen

(Runtime 4:02)

Read

More than 17 million acres in what is now Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana make up the historic homeland of the Nez Perce Tribe.

A nomadic people, they traveled through the seasons, hunting buffalo in the Great Plains and salmon fishing in Northwest rivers. They call themselves the Nimiipuu, which means “The People.”

The Nez Perce Tribe is headquartered in Lapwai, Idaho. Today they function as their own sovereign nation within the United States, with their own healthcare system, police force and tribal court.

“Law enforcement nationwide is struggling to fill positions, and we’re in that same boat,” said Patrol Sergeant John Svancara with the Nez Perce Tribal Police Department.

The department has the equipment to do the job, he said, they just don’t have enough officers.

As he drives around the grassy, golden hills of Lapwai on patrol, residents wave from neighborhood streets. Despite the friendliness of the locals, Svancara said videos shared on showing law enforcement misdeeds haven’t helped recruitment.

The other challenge is some of the local agencies don’t view tribal police as a professional police department, said Svancara.

Patrol Sergeant John Svancara on patrol in Lapwai, Idaho. (Credit: Lauren Paterson / NWPB)

“We work under the umbrella of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and we’re not quite state-certified police officers,” he said. “We’re in this limbo land of federal and state.”

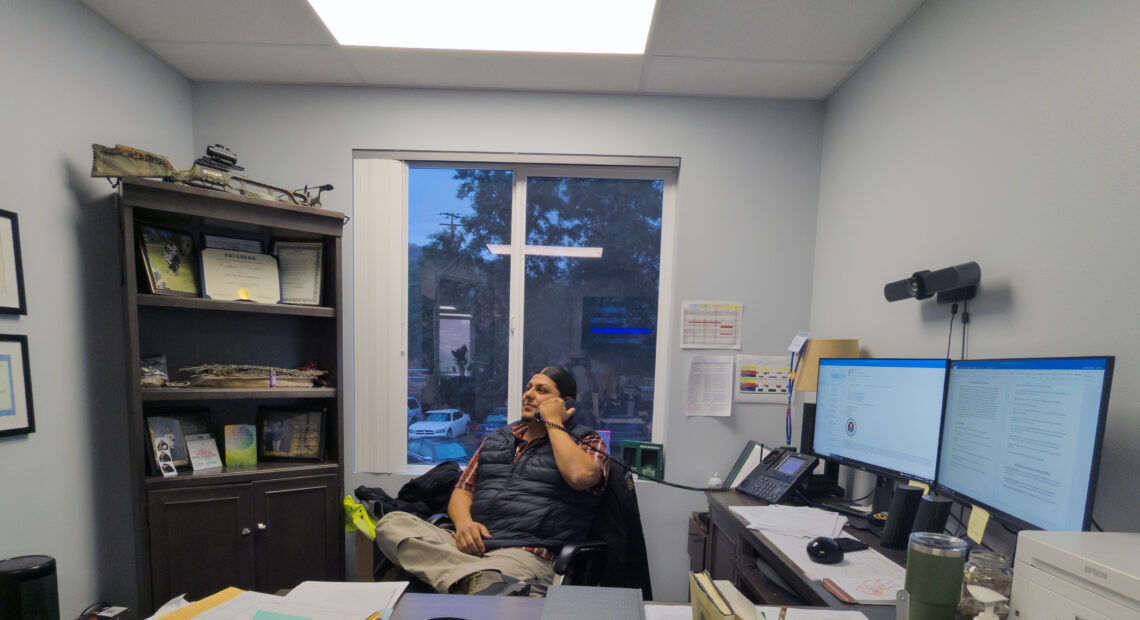

At the Nez Perce Tribal Police Station, Police Chief Leotis McCormack sits in a quiet office. He said a subcommittee made up of tribal representatives, law enforcement and members of the public is working to get Idaho’s legislative language changed so tribal police can be recognized as peace officers in the state, says McCormack.

A peace officer refers to positions in law enforcement where someone carries a badge and a firearm, focuses on preventing crime and has the power to arrest.

“Legally, it would allow us a lot of access to resources that we don’t have access to right now,” said McCormack.

Tribal police in the state would have access to the same type of training as state officers, without having to pay for it. It would also give tribes more power to respond to mental health situations, said McCormack.

If a tribal officer is dealing with a mental health emergency, McCormack says the department does not have the authority to put a hold on the person for their safety. Instead, tribal police must refer the person to the state.

“Even though we have the same training, even though we go to the same academies, even though we do the same work,” said McCormack. “Because that legislation doesn’t recognize us as peace officers within the State of Idaho, the state has to come in and do it.”

The subcommittee working toward getting tribal police recognized as peace officers had a meeting about the legislation in mid-October. The group is still collecting data and hearing testimony from community members at this stage, said McCormack.

In the meantime, along with state officers, tribes also have to work with federal law enforcement agencies.

“There are certain cases where tribal law enforcement and federal law enforcement or county law enforcement might not see eye to eye, but what I’m encouraged by is the level of communication that exists and that we’re helping to build off of,” said Joshua Hurwit, the United States Attorney for the District of Idaho.

Last month, a law enforcement workshop was held at the Nez Perce Tribe’s Clearwater River Casino and Lodge in Lewiston.

“We had law enforcement leaders from all the surrounding counties,” said Hurwit. “We had tribal leadership there. We had tribal law enforcement there. We had my office and some of our prosecutors there to talk about some specific issues like jurisdiction, to learn more about the tribe and think about how we can build even stronger collaborations.”

Passed in 2020, the Major Crimes Act gives U.S. attorneys like Hurwit the power to prosecute Native Americans who commit crimes on reservations, whether or not the victim is Indigenous.

Both Svancara and McCormack said the tribe has a good working relationship with Hurwit’s office.

Tribal police recognition as peace officers would help solve more Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples cases (MMIP cases) because it would give tribal officers more authority over people who are high risk, said McCormack.

“We’re losing our loved ones at rates that we just shouldn’t lose,” he said.

County jail facilities are not obligated to house tribal inmates, said McCormack. “We have had victims of violence watch their abusers be released from our custody because the jails will say they have no space,” he said. “If we had that recognition, counties would have that statutory obligation to house our offenders as well.”

Taxes on tobacco sold by the tribe are used for funding public safety. The majority of the budget for tribal law enforcement comes from tribal resources, with a small percentage coming from the federal government.

Whether or not they get support, tribal police will continue the work, said McCormack.

“It would be better if we had more resources. It would be better if we had more authority and we could expand our reach,” said McCormack.

Several positions were announced in June to place attorneys and coordinators across the U.S. to respond to MMIP cases as part of the MMIP Department of Justice efforts.

Once appointed, “A regional MMIP coordinator will oversee work in Oregon, California, Washington, Idaho and Montana,” said Kevin Sonoff, a public affairs officer with the United States’ Attorney’s Office in the District of Oregon.

Some are skeptical of the federal interests.

Every time the U.S. gets a new Attorney General, “They want to fix Indian Country,” said Ernie Weyend, a retired FBI agent who spent 19 years working in and around tribal communities.

“It’s hard for me to sit in front of people and make big promises when I’ve seen the history of these programs having the rug pulled out from under them,” said Weyend.

Programs at the local level like Tribal Community Response Plans (TCRPs) often work better as federal programs haven’t always been consistent, said Weyend.

TCRPs are often shaped around the needs and culture of tribal communities and allow tribes to take ownership of investigations and in responding to crimes.

“I think we’re making very good progress in terms of engagement with tribes, developing TCRPs, and ensuring there is a path to quickly integrate outside resources where somebody has gone missing,” said Weyend.

Although tribal community response plans take a lot of work and cooperation, “in the end, they can be done,” said Weyend.