Wildlife Groups Scramble For New Way To Block Grizzly Hunts

BY MATT VOLZ / ASSOCIATED PRESS

Wildlife advocates scrambled Thursday to find a new way to block grizzly bear hunts set to begin this weekend after a judge said he wouldn’t immediately restore federal protections on the bears living in and around Yellowstone National Park.

U.S. District Judge Dana Christensen’s delayed ruling prompted the advocates to hurriedly draft a request for a temporary restraining order that would block Saturday’s opening of the Wyoming and Idaho hunts, which would be the first in more than 40 years.

Mike Garrity, the executive director for plaintiff Alliance for the Wild Rockies, said it was essential to have a ruling before Saturday.

“It’s very important because 30 minutes before sunrise on Saturday morning, people could start killing bears,” Garrity said.

The groups plan to file an emergency request with the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals if Christensen rules against them, Tim Preso, an Earthjustice attorney representing several conservation groups and the Northern Cheyenne tribe, told the judge.

The advocacy groups claim the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision last year that Yellowstone grizzlies are no longer a threatened species was based on faulty science. They also say they don’t trust that the three states that have taken over bear management will ensure the bears’ survival. They are asking the judge to re-classify the bears as threatened.

Christensen said at the packed court hearing in Missoula that he would issue a decision as quickly as possible but did not say whether he would rule before Saturday.

Christensen asked Erik Petersen, Wyoming’s senior assistant attorney general, if his state would consider delaying the hunt until the judge’s ruling is issued. Petersen did not directly answer Christensen, but made a counteroffer to the judge.

Wyoming Gov. Matt Mead was willing to “make adjustments” to the hunting season, Petersen said, if the judge leaves Wyoming, Montana and Idaho in charge of managing the bears — even if he rules that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service needs to revise its rule declassifying grizzlies as threatened.

“The likelihood of any significant harm to the population is essentially nil,” Petersen said.

Christensen did not take Petersen up on his offer in the hearing.

Among their arguments in court, attorneys for the advocacy groups questioned how other threatened grizzly populations in the Lower 48 states would fare if the Yellowstone bears’ status changed. They also said the federal wildlife agency ignored recent spikes in overall bear deaths that, when hunting is added to the mix, could cause an unanticipated population decline.

Department of Justice attorneys said the Fish and Wildlife Service considered all the plaintiffs’ arguments and proceeded with lifting protections because there is no threat of extinction to the bears now or in the foreseeable future.

“They have a lot of speculation, (but) they have very little facts,” said attorney Michael Eitel.

Petersen and attorneys representing Montana and Idaho said the people most affected by the court’s decision will be the farmers and ranchers who live in grizzly territory and have increasing conflicts with bears attacking livestock. Those people have been cooperative with conservation efforts, but that attitude may change if federal protections are restored, they said.

“There are westerners who have to deal with this every day and who have apex-level predators in their backyard,” said Cody Wisniewski, a lawyer for the Wyoming Farm Bureau.

The population of grizzlies living in Yellowstone was classified as a threatened species in 1975, when its number had fallen to 136. The Fish and Wildlife Service initially declared a successful recovery for the Yellowstone population in 2007, but a federal judge ordered protections to remain in place while wildlife officials studied whether the decline of a major food source, whitebark pine seeds, could threaten the bears’ survival.

In 2017, the federal agency concluded that it had addressed all threats, and ruled that the grizzlies were no longer a threatened species needing restrictive federal protections.

That prompted six lawsuits challenging the agency’s decision. Those lawsuits have been consolidated into one case that Christensen heard on Thursday.

Idaho’s hunting quota is one bear. Wyoming’s hunt is in two phases: Sept. 1 opens the season in an outlying area with a quota of 12 bears, and Sept. 15 starts the season in prime grizzly habitat near Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks. One female or nine males can be killed in those areas.

Wildlife officials in those states say they’re ready for opening day, which would be Wyoming’s first grizzly hunt since 1974 and Idaho’s first since 1946. Twelve hunters in Wyoming and one in Idaho have been issued licenses out of the thousands who applied.

Montana officials decided not to hold a hunt this year. Bear hunting is not allowed in Yellowstone or Grand Teton.

Copyright 2018 Associated Press

Related Stories:

More grizzlies coming to the North Cascades

Grizzly bear in Yellowstone National Park. (Credit: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Listen (Runtime 0:58) Read Grizzly bears will be brought into Washington’s North Cascades. After more than 30 years… Continue Reading More grizzlies coming to the North Cascades

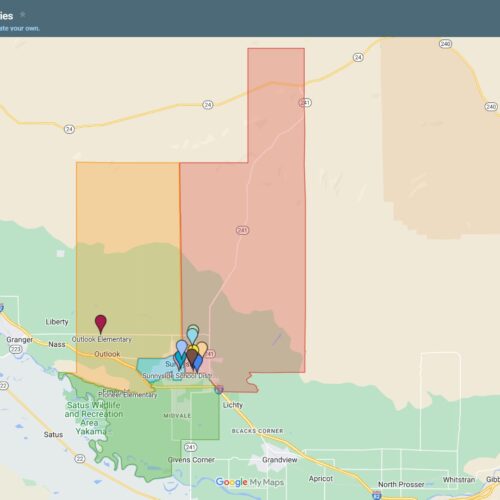

A return after seven decades: Inside the Yakama Nation’s elk hunt on the Hanford Reach

A group of elk runs from Yakama Nation hunters on the Hanford Reach National Monument in December 2023. (Credit: Star Diavolikis / Yakama Nation) Listen (Runtime 3:50) Read A video… Continue Reading A return after seven decades: Inside the Yakama Nation’s elk hunt on the Hanford Reach

Commercial timber owners in Washington will be able to apply for black bear damage permits

A black bear spotted on a forest road this spring in Eastern WA. (Courtesy: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife) Listen (Runtime 1:00) Read Permits to hunt black bears in… Continue Reading Commercial timber owners in Washington will be able to apply for black bear damage permits