Getting To Know Logan Wheeler, A Washington State Veteran And Alum Who Died A Century Ago

Listen

NOTE: This is a student multi-media project with Northwest Public Broadcasting. It was first aired and published for Veterans Day in November 2017.

BY KATHERINE BARNER & EMRY DINMAN

Sometimes we grieve for people we’ve never met. Walking through a cemetery, looking at the graves of people who exist to you only as names in stone, it’s easy to wonder at the loss. It’s a shallow grief, not the long-term grief for a friend lost, but the fleeting interjection of some unknowable person into your periphery.

For some, their jobs are to give life to those stone-wrought names.

FINDING LOGAN

“Well I kinda encountered Logan Wheeler by accident,” said Mark O’English, Washington State University Archivist.

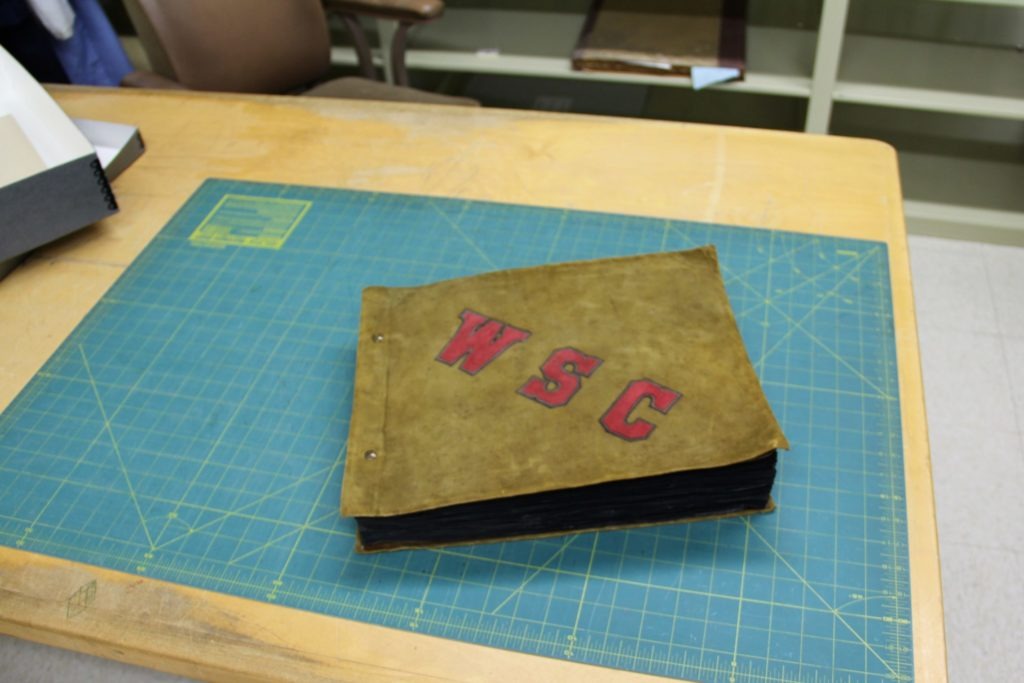

Mark was working on a project looking for a photo of the original WSU bookstore. During the search, he came across a 100-year-old leather-bound scrapbookembroidered with the name Logan Wheeler.

He did find the original bookstore in the background of one of these photos, but what stood out to him was this kid — a student — Logan Wheeler.

Logan was at WSU in the 1910’s. The album contained photos of himself and his friends around campus.

“He had these very informal frat photos. He went to San Francisco with Cadets and spent time at the Panama Pacific exposition in the summer of 1915,” Mark said. “There’s this odd random photo of someone posed with his chicken, and you kinda have this ‘why’ reaction.”

Since Mark found the photos he was looking for, he had to put the scrapbook away and move on to a new project about WSU Veterans.

While pursuing the new project he happened across a list of WSU casualties from World War One in James Quan’s book, “Heroes and Legends.”

The plaque that bears Logan’s name at the WSU War Memorial.

“I just get caught in the upper right hand corner, Logan Wheeler, it’s only like two lines, and it’s: Logan Wheeler killed in France 1918,” Mark said.

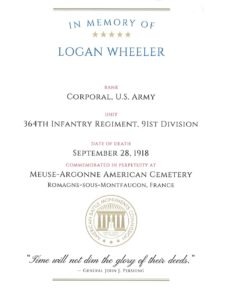

America joined the first World War the year before. As part of the 364th infantry regiment of the 91st Division, Logan Wheeler was among the 126,000 whose story ends in the Argonne Forest during the liberation of France. U.S. Supreme Court Justice William Douglas remembered Logan in his biography, “Of Men and Mountains,” as the first of his friends to die in France. Logan’s name adorns the WSU Veterans Memorial.

Logan died nearly a century ago, but for Mark, Logan went from a college kid who seemed to have unlimited potential to a dead soldier in all of 24 hours.

“It was one of these moments where the day before this kid came alive for me and the next day, he’s been dead for over 100 years,” Mark said. “I still choke up about it a little today.”

When Logan began this scrapbook he had no idea he would be fighting in France four years later. When Mark found the scrapbook, he didn’t know that Logan hadn’t lived a long life every bit as radiant as the one in the pictures.

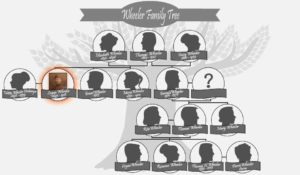

Though his photos feel timeless, Logan’s life before the war was not stagnant. His mother, brother, and sister had all died before he left for college. Not long after the death of Logan’s mother Elizabeth, his father Thomas remarried and had another son, Gerald Wheeler, who had looked up to his older brother both before and after the war.

Logan married his childhood sweetheart, Taletta, two days before he shipped out to Europe. A few days after news of Logan’s death reached Washington, Justice Douglas had walked past Taletta, and described in his biography the pallor of grief that hung across the widow’s face.

“It was then I realized, for the first time I think, what it meant when a war became ‘our war,’” Douglas wrote.

Sometime after Logan’s death, Taletta remarried. She never had children. As Logan had no children, the Elizabeth-Thomas line died with him. Gerald, Thomas’ half-brother, is the nearest relative to have descendants alive to this day.

The Wheeler Family Tree.

SCATTERED BY TIME

Logan’s obituary from 1918.

Logan’s story was scattered by time, essentially lost to the public. Logan’s family had largely died before him, his brother of meningitis and his sister of an unknown illness.

Only the half-brother Gerald had children, who are all deceased. The middle child, Thomas Wheeler, is survived by his wife, Dorris Wheeler, three children and four grandchildren.

Dorris said in a phone call that Thomas grew up on his father’s stories about Logan. Thomas shared these stories with Dorris and his children, passing on family legends even though Thomas had never met Logan.

Logan’s memory also resides at an American Legion building in Yakima that is named after him. The interior is vintage, some mix between a meeting hall and an old time bar where you’re as likely to get a malt or a beer.

Though the local veterans meet regularly in a building that bore Logan’s name, neither they nor the Wheeler family knew about the 135-page scrapbook that Mark had stumbled upon. All the while, Mark had none of the information that the legion building archived, including a copy of Logan’s obituary, written a decade after his death.

Gathering the disparate pieces of one soldier’s history and doing honor to that legacy symbolically honors all those unnamed who died alongside Logan, said Matt Steadman, sergeant-at-arms at the American Legion Post 36 in Yakima.

“You can’t remember everyone, but through him we can remember the sacrifices that they made back in the big war,” Steadman said.

The Legion building had a copy filed of a 1941 report detailing Logan’s death.

On September 26, 1918, two days before Logan died, he and another soldier, Wilson, went over a hill to fight Germans in the Argonne forest. Only 17 men from their company survived, including Logan and Wilson. The soldiers attached to another company. The next day, another firefight left only Logan and Wilson alive by nightfall.

On the morning of September 28, 1918, they met survivors of another company, and together the men tried to breach a machine gun nest.

It was during this assault that Logan was shot in the temple. Logan survived roughly 30 minutes. He handed a notebook to Wilson that detailed every ca

sualty in his company and the companies he was attached to over the past couple days.

The last words Logan Wheeler said to another human being, to Wilson, were, “Please give this to my superiors, I want it kept straight.”

As with many soldiers who died during the liberation of France, it was unclear where Logan was buried for years. The grave was only identified a decade later after an intensive search led by Daisy, Logan’s step-mother. Once he was found, she traveled half-way across the world to the Muesse-Argonne Cemetery in France to put flowers on Logan’s grave.

After stumbling across the gregarious and tragic life of Logan Wheeler, Mark said he has been changed forever. Stepping out from the library’s underground belly where he works, Mark sees students chatting and laughing with each other a century after Logan’s took his photos. He wonders what it would mean to send these students off to war, and what value the sacrifices of a young man 100 years ago holds for them.

Because of Mark O’English discovering Logan Wheeler’s scrapbook, the quote on his family tomb stone truly resonates.

Mark also wonders about a grave, one small plot among thousands half a world away.

“At some point in my life I hope I make it out to that cemetery in France and leave some flowers there,” Mark said.

Special thanks to Sueann Ramella, Mark O’English, and the folks at the Logan Wheeler American Legion Building. Original music by Jake Kargl.