A Memory Box of Craft: Moscow Writer Jeff P. Jones

If you spend enough time in Moscow, Idaho, you will run into a writer. It might be a faculty member from the University of Idaho or one of the graduate students in the school’s MFA program. It might be someone who has been both. You could bump into a writer at the Co-op or the Walmart parking lot, or even at Bonkerz, the indoor playground full of energetic children and their happy but weary-eyed parents.

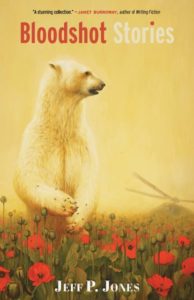

Jeff P. Jones is one of those writers you could find in any of these places. A graduate of the U of I MFA program and former instructor in the U-I department of English , Jones has recently released his first short story collection, “Bloodshot Stories” (Sunshot Press, 2018), which earned the 2017 Sunshot Book Award for short story collection.

The thirteen stories in the book represent about twenty years’ worth of work. During those twenty years, this former graduate student, whose working life began as a teacher, now works almost full time as a writer. He has also added the jobs of husband and father to his resume. “Everyone I know who writes has another source of income. Teaching is just a natural fit,” Jones says. He still teaches online courses.

For 2019, Jones has updated his book about the craft of writing, “Writing for the Reader: Practice in Prose Craft.” The update incorporates his article for The Writers’ Chronicle, the craft essay “At the Highest Point of Tension: The Art of the Artful Pause.”

“Bloodshot Stories” by Jeff P. Jones is on the long list for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Fiction. CREDIT: courtesy of author.

Other techniques Jones discusses in the book include freewriting, dialogue, creating tension, and using memory in creative writing. Publishing the craft book was “a way of formalizing the course packet, and to stay connected,” Jones says. “I didn’t want to forget all the stuff that went into it. It’s a memory box of craft.”

“Writing is always practice. It’s never perfected. It gets a little bit easier, but never gets easy.”

Bloodshot Stories includes “Riven,” where Jones imagines a nuclear explosion that destroys Seattle. He does so without an obvious central character.

“I knew nothing about atomic bombs,” Jones says of the research that went into the 12-page story. “At first, I’m reading for exploration and the parts that feel the most interesting. At some point, you feel ready to write.” While he says he did his best to be as true to the facts as he could, he also says he’s not afraid to play around when necessary.

“You can get away with whatever you can get away with,” Jones says. In “Riven,” he sticks to the truth. using his researched facts about nuclear detonations and building a story around it. But he is, after all, a writer of fiction: “If you can’t change reality in fiction, then what’s the point?”

For his Bonnie and Clyde novel “Love Give Us One Death,” Jones spent seven years in research and writing. Before that, he abandoned another novel after almost 100 pages of writing. He says he never intends to go back to that unfinished project, but that doesn’t mean he forgets it.

“I’m happy to let a story sit. I’ll work on it and put it away,” says Jones. “Part of that is to allow for growth as a person and a writer. You have to change. You may not be ready to write that story, and forcing it isn’t going to get it there.”

Now, as a husband, father, and teacher, Jones doesn’t have time to force things that aren’t ready. “Weekends are for writing,” he said, “but I’m always thinking about it. Once you have kids, it’s hard to hold yourself to a schedule.” He describes his writing schedule as “catch as catch can.”

“The cool thing is, you only get better with more life experience,” Jones said.

Bloodshot Stories was one of 10 books on the long list for the PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize–whose winners include Spokane author Shawn Vestal–did not make the list of five finalists.

Jones reflects on the challenge of dealing with recognition, or the lack of it, in the world of literary awards. “I feel grateful that writers I really admire read my book, let alone comment on it,” he says. “I’m trying to experience the highs because they don’t last.”

Jones reminds other writers that writing is a solitary job, and that rejection that is more normal than acceptance.

“You only get so many phone calls that say [something has been accepted]. It’s OK to feel good about your accomplishments.”

Related Stories:

Grave Stories: Touring Walla Walla’s Mountain View Cemetery

Fallen soldiers, outlaws, bankers, a madame, and maybe even a couple of witches all reside in one place now. It isn’t the set up for a bad bar joke, though.

Mountain View Cemetery in Walla Walla is the earthly home to these and other deceased figures.

‘Not The Time To Slow Down’: RAPtivist Aisha Fukushima Returns To Walla Walla

Aisha Fukushima has a story to tell about hip-hop and rap, but it’s not the only story there is. Fukushima, a 2009 graduate of Whitman College in Walla Walla, returns May 19 to share this story and her world-wide journey as an artist and activist as Whitman’s 2019 commencement speaker.

Ring The Bell: Regional Pro Wrestling Brings Out Crowds And Nostalgia

In the Northwest, promotions such as Seattle-based Defy, Thrash out of British Columbia, and Prestige Wrestling in Hermiston, are out to remind fans of wrestlings roots and its future. While not as many promotions are running in the region as in places such as the South and Mid-Atlantic regions, indie wrestling is growing.