Columbia River Treaty Renegotiation Brings Out Crowd And Contention In Tri-Cities

READ ON

The Columbia River Treaty is costing U.S. ratepayers and public utility districts too much. That was the broad sentiment at a sometimes-tense town hall Monday about ongoing treaty negotiations.

At the Richland meeting, negotiating officials laid out the complicated back-and-forth between the U.S. and Canada. A panel of U.S. negotiators listened to people’s concerns, including worries about the cost of downstream power benefits, transparency of the talks, ecosystem protections and climate change.

Modernizing The Treaty

The treaty has guided flood control and hydropower operations along the Columbia River since the early 1960s. Now the U.S. and Canada are modernizing it.

As it stands, dam operators in the U.S. must deliver electricity to Canada in exchange for its water storage. Regional public utility district managers said that price is too high.

Gary Ivory, with the Douglas County Utility District, called it an “undue burden.”

“You’re looking into the face of the people who actually pay the burden of this Columbia River Treaty,” Ivory said. “We feel like this is kind of like having a millstone hung around your neck. It’s unbalanced. It’s unfair.”

Ivory said that for central Washington’s Douglas County, that payment amounts to $500 per customer per year.

Negotiators wouldn’t give specifics but said they hope to lower what’s called “Canadian Entitlement.”

“We believe that anything less than a 90% reduction (of the entitlement) is going to be a failure on your part,” Ivory told the panel of negotiators.

People also complained that process is taking too long. They said negotiators were “stonewalling” their questions about transparency.

Jill Smail, the lead negotiator for the U.S. State Department, said having back-and-forth conversations in public wouldn’t benefit the negotiations.

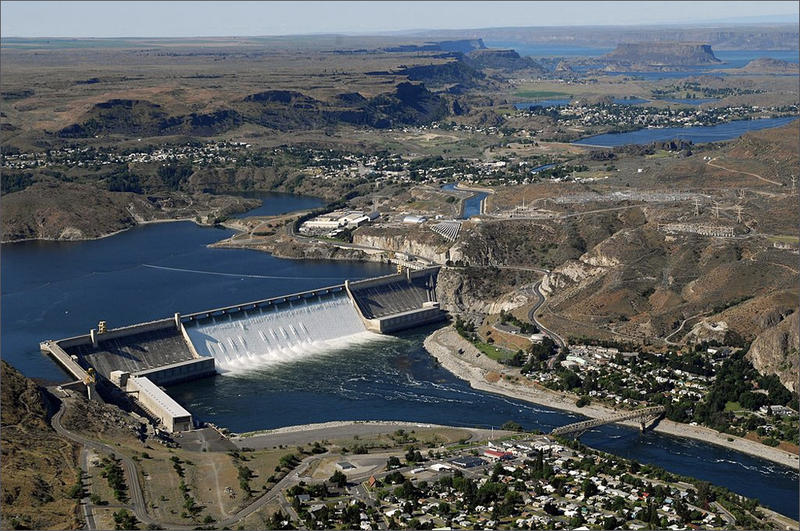

When the Grand Coulee Dam was built between 1933 and 1941, it effectively blocked salmon from traveling to the upper reaches of the Columbia River. CREDIT: U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

“The reason that we’re having (the meetings) in confidence is because we need to have these hard conversations on the issues people have brought up tonight,” Smail said. “Both countries recognize that, and that’s the process we’ve chosen.”

Several conservationists asked the negotiators to add in support for ecosystems and fish protection, something they’ve said is a goal for both countries. Smail said both countries already use the treaty to help augment flows to benefit salmon.

“We will seek opportunities to build upon the region’s investments and the treaty’s flexibility to improve ecosystem cooperation for the benefit of fish and wildlife in both countries,” Smail said.

To move toward resolving an earlier controversy – when U.S. tribes weren’t involved in the official negotiations – Smail said three tribal representatives were at the most recent negotiations in British Columbia. She said negotiators also consult with tribes before and after meetings.

“Some of them were able to join us as ‘expert advisors,’” Smail said. “We were thrilled to have them with us and to benefit from their expertise and experience. I think that we’re going to continue this positive work with the tribes moving forward.”

A group from the Lower Columbia Basin Audubon Society asked that negotiators also remember birds rely on fish..

“The bald eagle is very much reliant on the Columbia River, as a feeding source for fish, so I want to make sure that you negotiate well to maintain the water flows in the river for salmon,” said Dana Ward with the Audubon Society.

Request Of Congressman Newhouse

The U.S. State Department and the Northwest Power and Conservation Council hosted the public meeting, at the request of U.S. Rep. Dan Newhouse. Officials had previously held meetings in Spokane, Portland, Boise and Kalispell, Montana.

Newhouse pushed for the meetings to give people in the Mid-Columbia a chance to voice their concerns.

“There’s a critical juncture here that we have an opportunity to renegotiate the terms of this treaty that can make it even better for us and Canada,” Newhouse said in an opening statement Monday evening.

The current treaty framework will change in 2024, when Smail said the flood control aspect is “less defined approach in terms of operations and payment.” There is no timeline yet on when the modernization of the treaty will be finalized.

Related Stories:

Preliminary agreement reached for a modernized Columbia River Treaty

The Columbia River west of the Gorge as it heads toward Portland and out to the Pacific Ocean. (Credit: Amelia Templeton / OPB) Listen (Runtime 1:01) Read After more than

Salmon advocates ask to include healthy ecosystems in Columbia River Treaty

Salmon advocates want negotiators to consider salmon and the Columbia River’s ecosystem as a part of an agreement between the U.S. and Canada.

‘Do Something Big’: Photographer Helps Tell Columbia River History In ‘Healing The Big River’ Book

Peter Marbach says he wanted to use his photography to tell the story of the Columbia River, to move from purely landscape images to a more social justice-driven book. To do that, he needed help — from the First Nations communities most affected by the development of dams along the river.