Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

BY JACKI HEDLUND TYLER

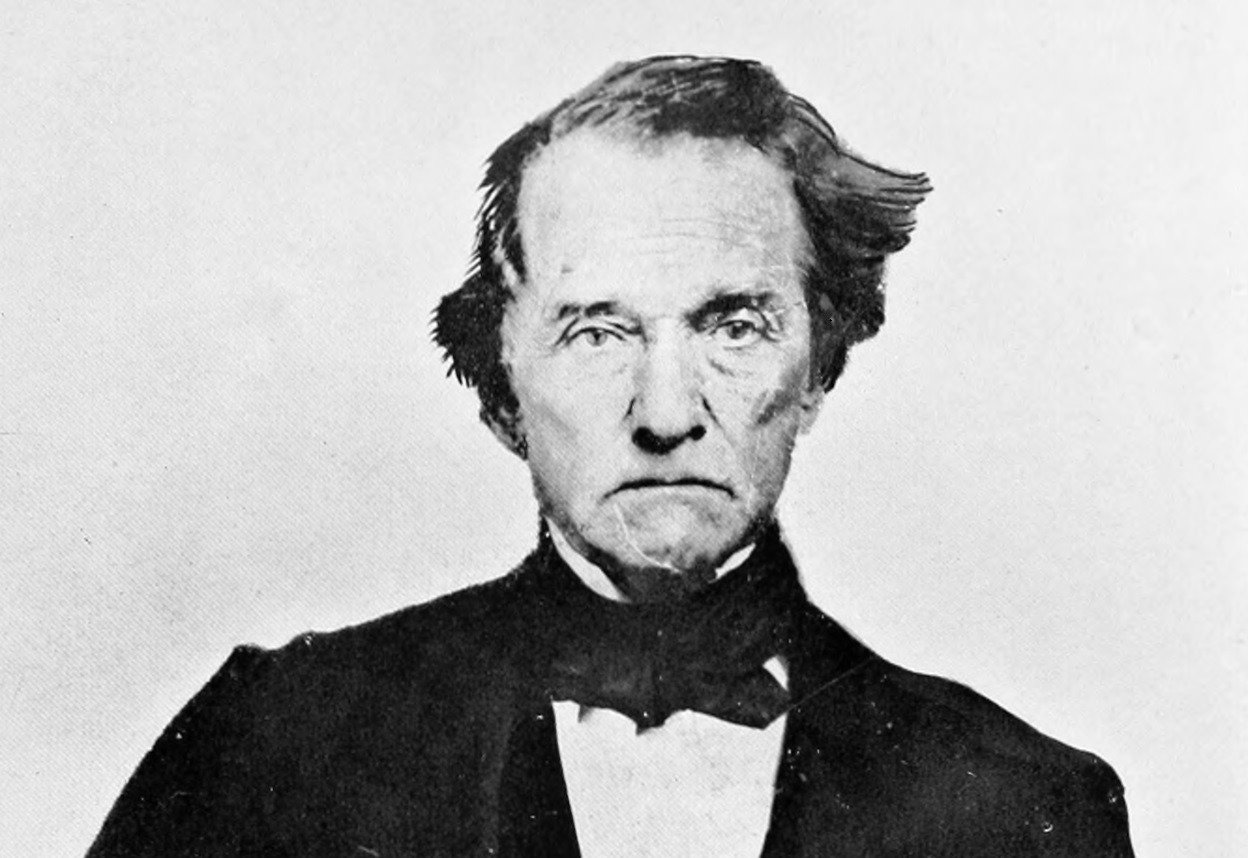

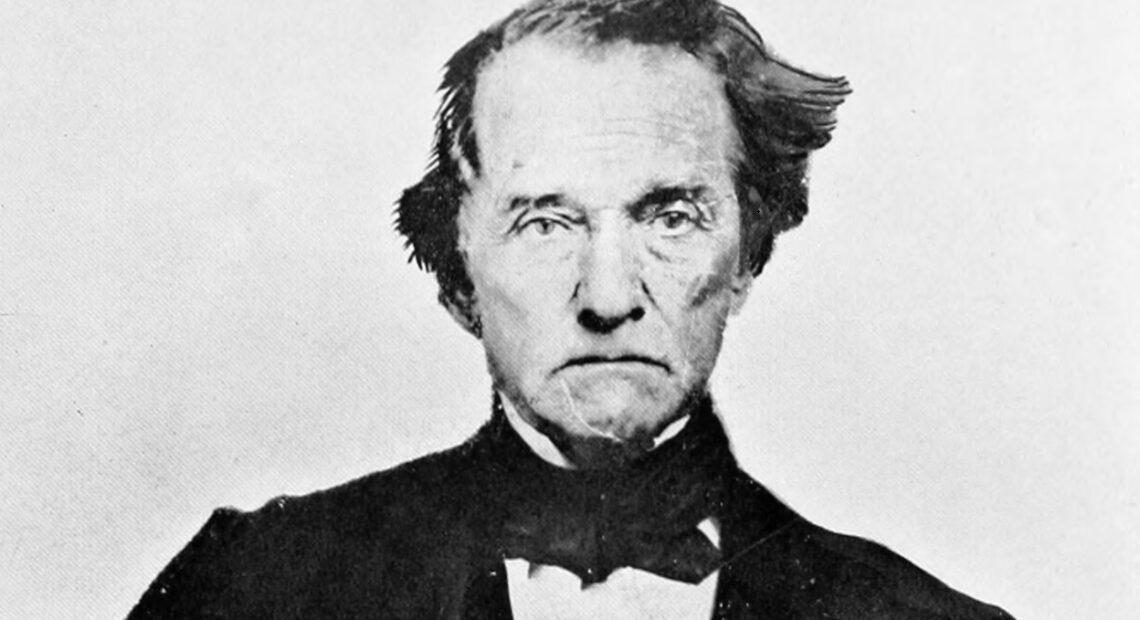

Politicians have employed gendered epithets to shock, insult, and challenge the legitimacy of other officials since the establishment of political systems in the United States. Throughout the 19th century, male politicians used language to overtly feminize other men. The term “granny” began to appear in U.S. newspapers in the 1820s as a means to insult politicians, but the intentional association of an opponent with an elderly woman gained national attention during the 1840 presidential election when supporters of President Van Buren consistently referred to his challenger (General William Henry Harrison) as “Granny Harrison.” After the death of President Harrison and the weakening of the two-party system in the U.S., however, usage of the term “granny” seemed to fall out of favor, except in the Pacific Northwest.

Jacki Hedlund Tyler, Assistant Professor of History at Eastern Washington University, and author of Leveraging an Empire: Settler Colonialism and the Legalities of Citizenship in the Pacific Northwest.

By the 1840s and through the 1850s, Oregon Democrats embraced the gendered epithet of “granny” using it against politicians who opposed the institution of slavery. Whether they were men with very public anti-slavery sentiments, such as The Oregonian editor Thomas Dryer, or a local group of men who met to discuss the newly emerging Republican Party, Oregon Democrats referred to these men as “grannies.” Most notably politicians referred to men as being women if they supported abolitionism. Women were active participants in abolition societies, and in Oregon, supporters of slavery equated the presence of women in those organizations with femininity and referred to all of those in attendance as women.

Calling political opponents “granny” and other gendered epithets was a tactic that lasted well after the Civil War. Being associated with a woman, regardless of her age, continued to be an insult even after women received the right to vote and gained political enfranchisement. In fact, associating a male identified politician as a woman or with feminine attributes is still used as an insult in American politics today. The insinuation that women’s presence in politics is less valid than men’s participation continues to be deployed across media platforms by politicians as well as the general public. Of course the more diverse representation of gender among modern politicians has brought about a larger selection of gendered epithets to employ. Opponents of Oregon Governor Kate Brown, the first openly bisexual governor in U.S. history, have used a variety of gender-based insults to challenge her work and her official position. Additionally, and perhaps most commonly, opponents drop her elected title and refer to the governor only by her first name.

So why did Oregon Democrats continue to use “granny” and related terms to challenge the legitimacy of their opponents? This may be because gendered insults worked particularly well in a two-party system. While Oregon had multiple political parties leading up to the Civil War, the dominance of the Democrats meant they could lump everyone in opposition together. Overall, language and definitions of gender—along with race—existed in both the political discourse and legislation of the Oregon Territory as a way to exclude specific groups of people from rights as citizens. Today, U.S. politics presents a very distinctive two-party system, and perhaps this is one of the reasons why gendered epithets are still used, but what constitutes an insult today is more a legacy of gender inequalities than of the party systems.

Related Stories:

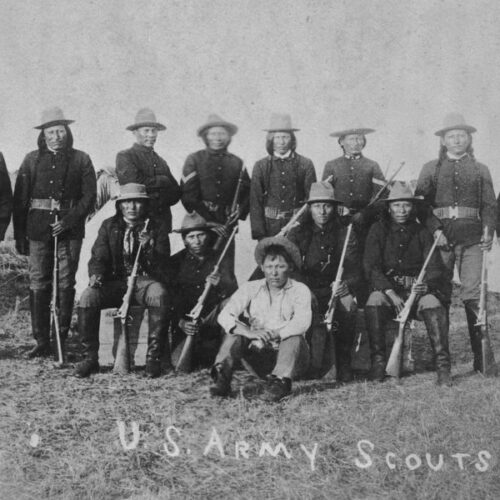

Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

The story of some Native American Scouts and their complicated reasons for working with the United States government.

Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

In this Past as Prologue essay, WSU Professor Karen Phoenix explains the history of the shipping container and its Spokane ties.

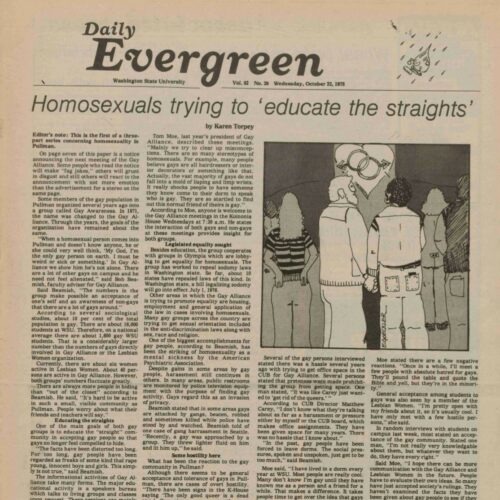

Past As Prologue: Rural Places Are Queer Places And The History Of WSU’s LGBTQ Awareness

What the struggle over recognition for WSU’s Gay Awareness student group shows is some of the similarities between rural and urban LGBTQ rights. Rural areas — especially college towns like Pullman or Moscow — are also queer places. People in cities who were against gay rights used the same tactic as those in Pullman—the public-referendum—to deny housing or employment equality to LGBTQ people.