Hanford’s Waste Treatment Plant churns out first container of clean test glass

Listen

(Runtime 1:26)

Read

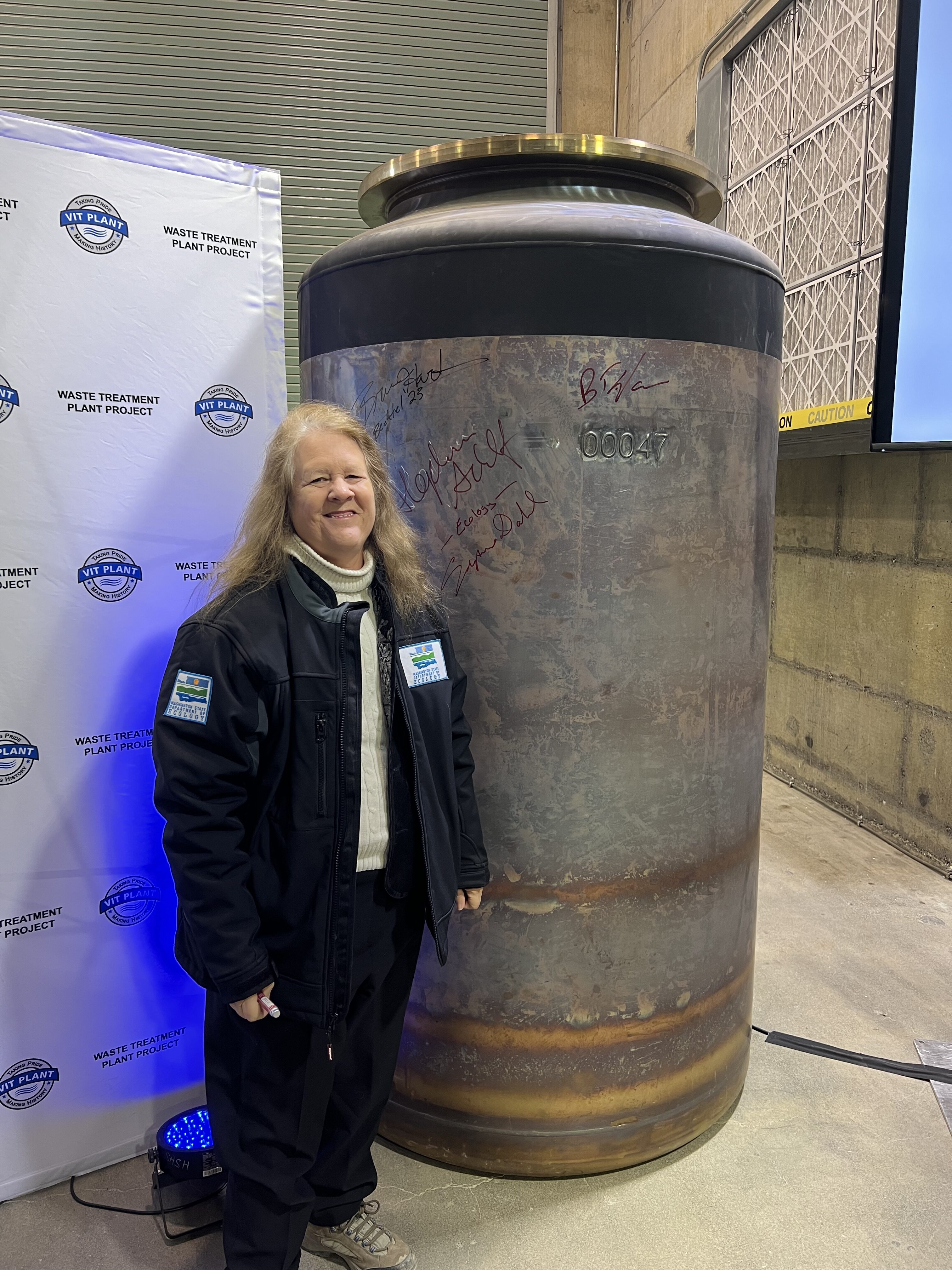

It’s a big test baby: Hanford’s Waste Treatment Plant marked the arrival of its first nearly 7-ton canister of test glass.

Top managers and workers gathered in one of the massive facilities’ frigid export bays to celebrate the birth of the test glass at the radioactive cleanup site in southeast Washington.

The glass canisters will eventually bind radioactive waste that’s stewing at Hanford in aging underground tanks. There are 56 million gallons of the stuff.

“It’s really not just us, it’s 20 years worth of effort by folks at the Department of Energy, certainly our Bechtel teammates, and many, many people past and present who have contributed to this colossal event for our site and our team today,” said Brian Vance, U.S. Department of Energy’s top manager at Hanford. “Every contractor on the site has a piece of that canister today.”

This behemoth container is seven and a half feet tall and four feet wide. It looks like an overgrown, old-style milk canister. Only, the federal contractors aren’t putting milk in it.

Washington Ecology’s Suzanne Dahl stands next to the first container of glass poured at the Waste Treatment Plant at Hanford.

(Photo courtesy of Washington State Department of Ecology)

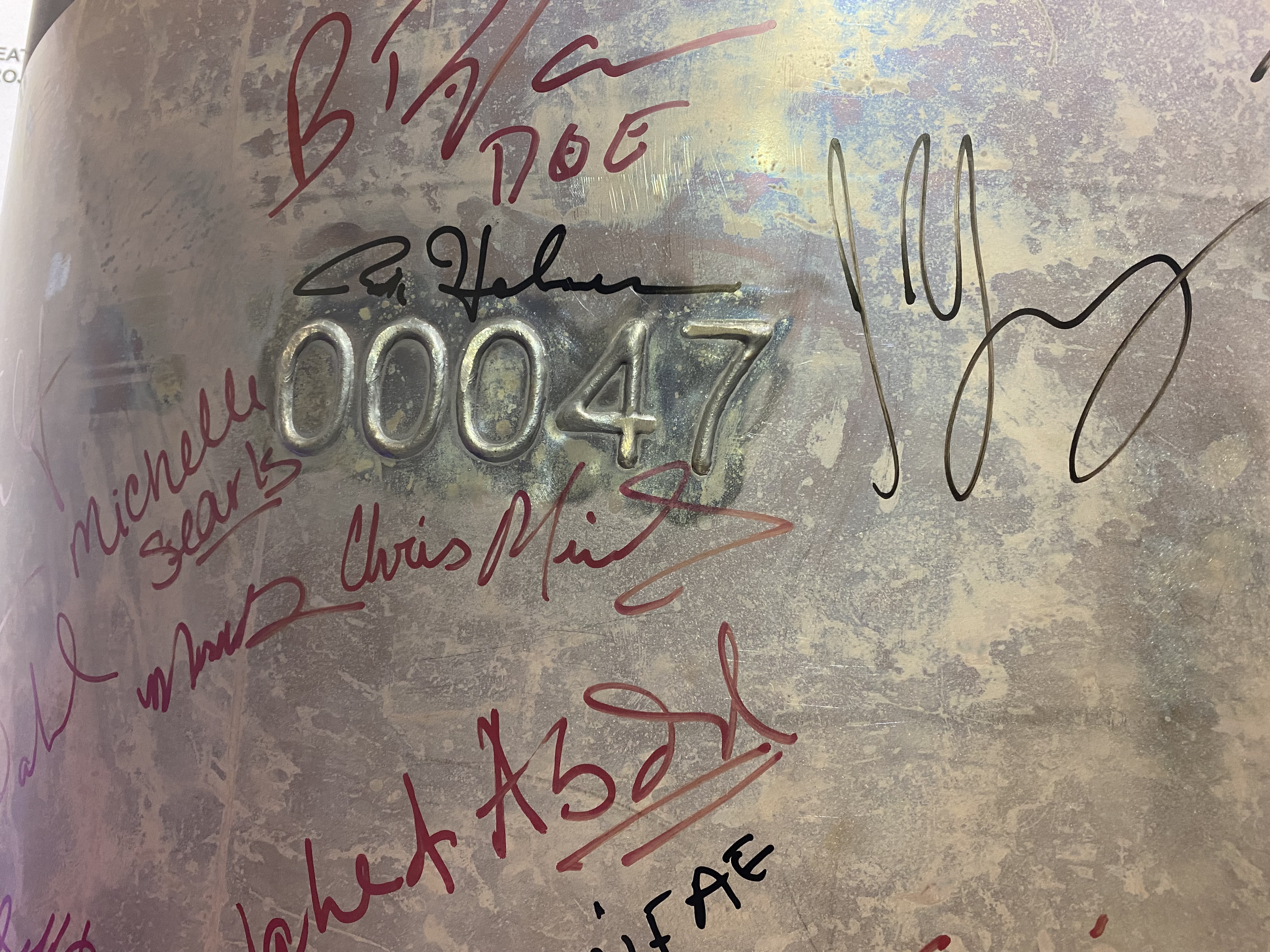

New baby 00047

Number 00047, the first canister, carries the initial pours of molten glass from the Waste Treatment Plant. Now cooled, the canister has a dulled surface from the extreme heat of multiple pours. Managers stood around it taking pictures and signing their names on the side of the container. Washington’s two U.S. Senators, Patty Murray and Maria Cantwell, sent along video messages, along with Congressman Dan Newhouse.

Suzanne Dahl is Washington’s go-to for the Waste Treatment Plant at Hanford. Her office is littered with boxes of documents from Hanford she has reviewed. Dahl, the tank waste treatment section manager for the state Ecology department, said that to make test glass here after 20 years is awesome.

“So, we’ve had people have kids be born and graduate. We’ve had people pass away while still working on this,” Dahl said. “I’m really looking forward to when Hanford tank waste ends up in glass.”

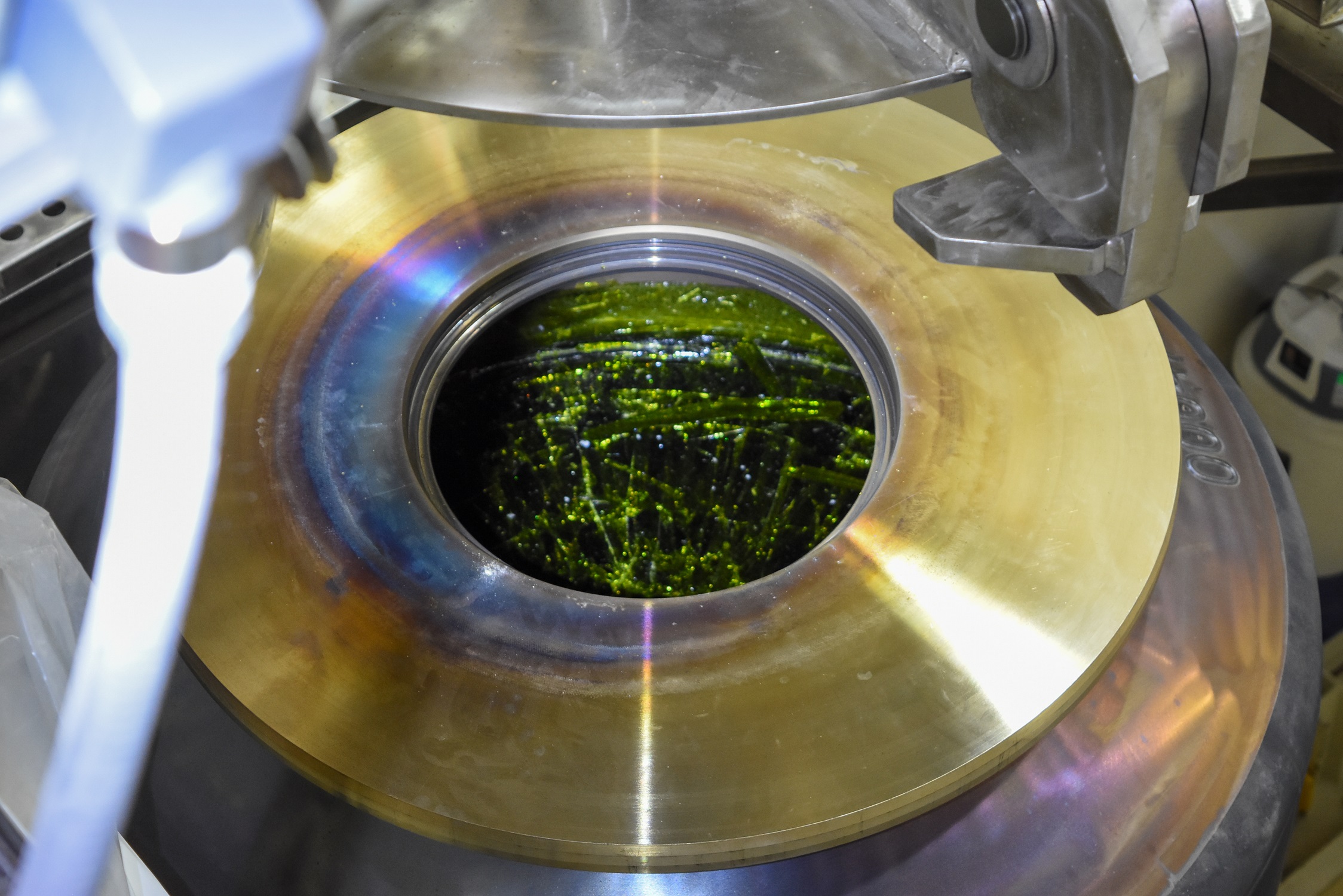

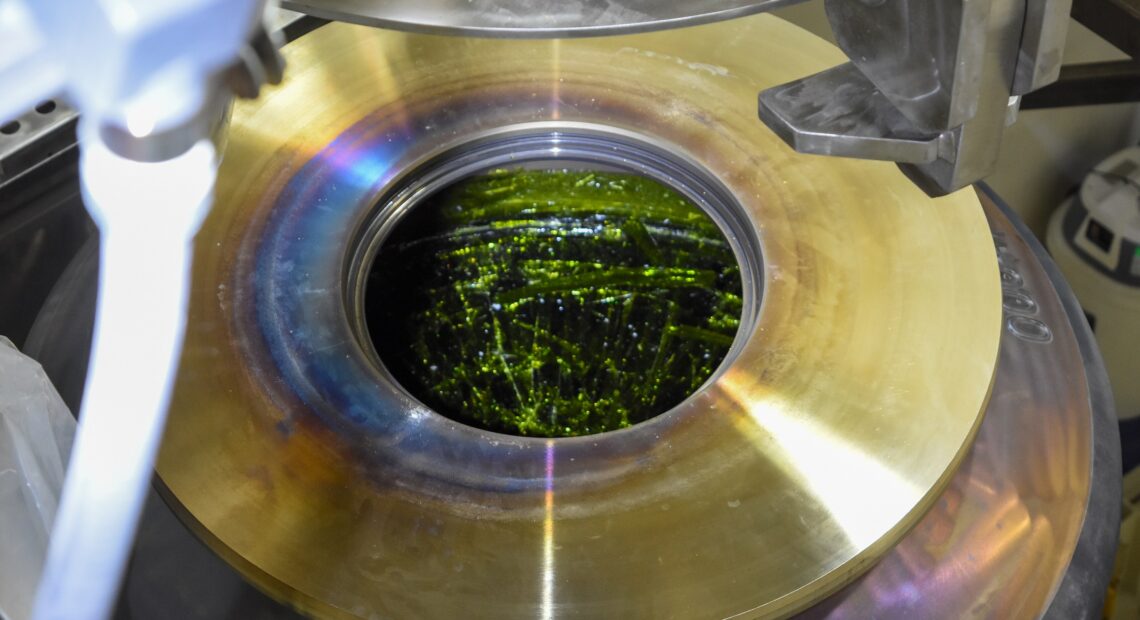

This is a big moment. This glass baby is a long-wanted child. In 2000, the current design began. Ground broke the next year. It’s been a difficult gestation: Technical problems, complex waste, a tangled design-build process, questionable parts and equipment, deep federal investigations, fraudulent labor billing, high-profile whistleblowers, and safety culture issues, now about two decades later – the first emerald-green glass.

Brian Hartman, project director and Bechtel senior vice president, said many of the plant’s problems have been worked out.

“Now, we can just get into making the equipment do what it’s supposed to do and make sure we can move forward and be able to take care of the environment and the community for the future,” Hartman said.

The next canister of waste is named 00102 and has begun being poured. The random numbers are how the containers are moved from storage with the forklifts, project spokespeople said.

Top managers signed cast 00047 – the first glass produced at the Waste Treatment Plant at Hanford.

(Photo by Anna King.)

Tanks await

This effort could help bind 56 million gallons of radioactive waste stored in hundreds of nearby underground tanks at Hanford not far from the Columbia River. Some tanks sit stewing just within sight of the plant, fenced off and graveled – a grim reminder of the daunting work ahead. Some are confirmed to be leaking.

The plant already started pouring its second container and will keep repeating that process until 2025, when the plant is scheduled to go hot – when radioactive waste will be introduced to the glass process.

Once fully operational, the plant will process about 5,300 gallons of tank waste each day and fill nearly four containers each day, Bechtel said. The two massive melters in the facility heat to 2,100 degrees Fahrenheit.

Running at full-tilt, the plant is projected to run until 2070 to complete treating all of the low-activity and high-level waste, said an Energy spokesperson. 90% of the volume of waste is low-activity waste. Federal and state agencies are still debating the best method for binding up high-level waste.

The containers of vitrified low-activity waste will be trucked from the plant to the Hanford Site’s Integrated Disposal Facility. The high-level waste was slated to be stored in a deep geologic repository, Nevada’s Yucca Mountain, but that plan’s been largely scuttled.

Written in stone

Whether Hanford’s plant goes hot safely in 2025 is still to be written.

Sitting on folding chairs in the frigid export bay at the plant, three managers in cowboy boots, work boots and hefty jackets waited for the speeches.

They all agreed this day was a big deal. They said they had been working toward it for a long time.

One manager said he remembers coming to the Tri-Cities from another Department of Energy site – Savannah River – in about 2008. He said at the time, he was told Hanford’s Waste Treatment Plant construction was a five-year project.

At home, he still has a little soapstone dump truck figurine. It was given to many workers on the site, who hoped for the first glass to emerge more than a decade ago.