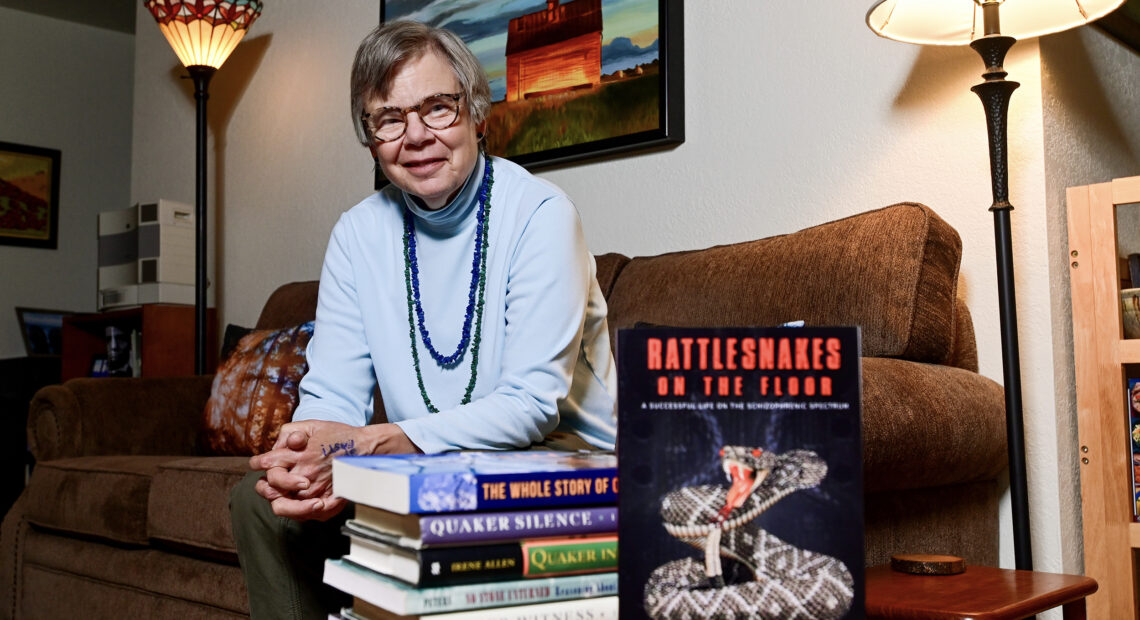

Moscow author’s book illuminates inner world on the schizophrenic spectrum

Listen

(Runtime 4:09)

Read

E. Kirsten Peters has written a lot in her lifetime. Among her works are two different geology textbooks, a nationally syndicated “Rock Doc” newspaper column, a book by the same name and four murder mysteries under a pen name.

Peters’ latest book, “Rattlesnakes on the Floor,” diverges from any of her previous endeavors. It’s a story she held onto, without telling anyone, until her mid-50s

“I probably couldn’t have done it when I was younger,” she said. “I was still trying to make my way in the world.”

In the book’s introduction, Peters recalls a stay at the St. Joseph Regional Medical Center inpatient behavioral health floor in Lewiston. She’s shooting hoops in the hospital’s small exercise room with only the supervising nurse for company, she writes, but she begins to feel the presence of teammates and bleachers full of people cheering her on.

“I don’t literally see anyone else on the hardwood floor, but at a visceral level I feel surrounded by wonderfully supportive teammates,” Peters writes.

On one hand, Peters knows there are no teammates, nor an audience watching from spectral bleachers.

On the other, the experience is so real to her, and so profoundly moving, that as she begins to lose her connection to those invisible people, she can’t help but search for them.

She describes going back to the exercise room and reaching to touch the wall where she had once felt their presence.

“My outstretched hand encounters only sheetrock, unlike the hoped-for permeability,” she writes. “In desperation, I move my hand upward, trying to draw the curtain of reality away from the wall, hoping against hope there is still some way to rejoin the souls I have come to know beyond the gypsum boards.”

The experience is one of two sides to Peters’ illness. Some, like the one in the hospital’s exercise room, are positive — what Peters feels is best described as a “mystical experience,” though she acknowledges those experiences are also a part of her diagnosis. Many of the other symptoms she’s lived with for decades are, at times, debilitating.

Now 63, Peters defies stereotypes commonly associated with people on the schizophrenic spectrum.

“Most people think of schizo anything as being a bum on the sidewalk in Spokane,” she said. “That just isn’t fair to those of us who have serious diagnoses.”

A graduate of both Harvard and Princeton, and respected academic, Peters is far from that caricature. Starting in middle school, she said, she would hear things and occasionally experience visual hallucinations.

She recalled telling her pediatrician about one of the first hallucinations she had, where she heard maniacal laughter while drawing a bath.

It’s one that’s recurred throughout her life, along with hearing what felt like encoded messages, or, as the name of the book suggests, feeling the presence of swarming masses of rattlesnakes on the floor by her feet.

When, as a child, Peters brought up that laughter she heard, she was briskly told by her pediatrician she would “have to see a psychiatrist if that kept up.”

That encounter set Peters down a path of hiding many of her symptoms from loved ones, she said, and denying parts of her own experience to even herself, and to doctors, for decades.

It wasn’t until after the death of both Peters’ parents, when she was 55 years old, that she would admit her experiences of hallucinations and delusions to her psychologist and psychiatrist.

By that time, she was accustomed to regular appointments with mental health professionals and had several stays in the psych ward under her belt. Still, she kept those experiences hidden for most of her life. Part of it, she said, was an attempt to protect her parents who might have felt her severe mental illness was somehow their fault.

“People in their generation were taught that mental illness shouldn’t be discussed, that mental illness was the fault of the family. I had a stable and loving home life,” she said. “I knew if I said I’ve been hearing things, that the diagnosis would get worse and that they would feel that keenly.”

Because of that denial, Peters said, when she was given the diagnosis of depression as a teenager, she took it as fact.

As she moved into early adulthood, she said, her symptoms progressed, causing more and more suffering that became harder to ignore. Peters’ symptoms worsened while she was an undergraduate at Princeton, leading to chronic insomnia and weight loss.

Medical providers at the university’s health clinic offered no helpful remedies, she said, but suggested tea and warm milk for her insomnia. Those suggestions made no difference in the dissociative manic states brought on by what Peters’ providers would, years later, diagnose as schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

Peters struggled through many of these periods throughout her life, at times contemplating and making plans for suicide, even as she sought relief through exercise, religion, writing and a series of medications prescribed by psychiatrists.

Unable to find the words to describe her struggles as a young woman, Peters said, she often turned to bottles of cheap whiskey to help her fall asleep. During numerous visits to psychiatric units throughout her life, Peters said, she found that was a commonality among many patients. “I drank my head off when I was young and so did they,” she said.

Though Peters never told her parents about the severity of what she experienced, she said, she also feels she owes them her life. Time and time again, when the severity of her illness became too much to bear on her own, her family took her in.

“When I came home from Princeton the summer after my freshman year, they didn’t know what was wrong with their beloved daughter,” she wrote. “But they were willing to do anything they could to be useful.”

Even in the depths of that illness, Peters often returned to studies and academia. To some degree, she said, the academic rigor of the environment she pursued, along with her writing, helped her keep going.

“If I can immerse my mind in what I’m writing, then I don’t have to fear the rattlesnakes on the floor,” she said. “So, it’s a way of escape, for me to concentrate on something.”

There were few support systems for people with severe mental illness in academic institutions when she arrived at Princeton, Peters said. Had she admitted the severity of her illness, she said, she might have found herself cut off from pursuing her passions.

“It could have been much better,” she said. “I hope very much for the young people that they get better medical care than I did.”

After earning her doctorate, Peters returned home. She would once again rely on the support of her parents before finding enough stability to work full time and move into her own home.

For most of what she remembers, she said, her life has been a series of two steps forward and one step back.

More than once, Peters and her psychiatrist would find a combination of medications that worked to manage her symptoms for a period of time, before, after weeks, months or years, she fell back into a tailspin of having to repeat the process — sometimes under inpatient care when she posed too high a risk to herself.

Still, Peters also found great joys in her work and life. After Harvard, she went on to teach at Washington State University, worked at the Moscow-Pullman Daily News and eventually took a public relations job. She hiked the region with her dogs, traveled and pursued side projects writing outside of her job, including a book on climate change.

She continued this work until memory challenges a few years ago, likely worsened by prescriptions vital for her mental stability, made her job difficult and led to her disability retirement.

Peters’ survival into her 60s is no small feat. People with schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia are at significantly increased risk of mortality compared to the general population. One study between 1950 and 2015, looking at people with such diagnoses, found 44% deceased at the end of the study and a median survival following diagnosis of 36.2 years.

In her book, Peters details some of her many encounters with doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists throughout her life.

Some of those medical professionals provided insights and helped narrow down prescriptions essential in keeping her stable and alive for decades. Others, perhaps blinded by preconceived notions, were less helpful.

One doctor, whom Peters saw while studying at Harvard, was convinced the majority of her illness must be derived from some unexplored trauma related to her religious upbringing, she said.

The doctors who were unable to help her, Peters noted in her book, often seemed uninterested in hearing much about her own perspective and experience.

Peters’ survival, as she tells it, may also be in large part thanks to a series of friends, strangers and relatives who helped her in times of need: a nun she spoke with at a psychiatric ward, a sister-in-law who rescued Peters when her mental illness became debilitating during a trip that was states away, a neighbor who helped her apply for disability benefits.

Throughout the book, Peters paints a clear picture of two parts of herself strangers are sometimes surprised to find coexisting: a successful, articulate and determined academic and a person who, for more than 50 years, wrestled with debilitating mental illness.

On several occasions, Peters said, she’s given talks to local groups in the community. Most people, she said, never expect someone with frequent hallucinations and delusions to accomplish the kinds of things she has.

“That blew away their stereotype,” she said.

Without romanticizing her illness, Peters is also unapologetic about herself and her experience, relaying both the deep pains the disorder caused her and its silver linings. Her manic states, for instance, led not only to overwhelm and insomnia, but to the completion of near-Herculean feats in her writing and academic pursuits.

Peters also brings a degree of levity to her account of life with schizoaffective disorder, recounting how she decided to loan her truck to a family friend in need.

“A couple days later I changed my mind about the loan and simply signed the vehicle’s title over to him, a decision vindicated by his exuberant joy,” she wrote. “As I like to say, there’s no point in being manic if you don’t know how to use it.”

She didn’t write the book to make money, Peters said, noting she is well aware self-published books rarely are lucrative.

“I’m doing it because I really believe in getting the word out that severe mental illness doesn’t have to be the end of the story,” she said.

“Rattlesnakes on the Floor,” Peters said, was born, in part, out of a desire to share from the perspective of someone with severe mental illness. It’s a perspective that’s rarely heard, she said, and something loved ones and doctors stand to benefit from hearing.

“Some of the most admirable people I know have been my fellow patients,” she said. “For whatever reason, I have the skills to write, and if I can speak on behalf of folks who have a similar diagnosis to my own, that really matters to me.”

For those without mental illness, the book opens the door to understanding loved ones and patients a little bit better. For those living with it, Peters said, it shows the possibilities for a life well-lived, even amid internal battles that only sometimes surface for the rest of the world to see.

“Rattlesnakes on the Floor” is available at BookPeople of Moscow and on Amazon.