A Sheepherder On Two Decades In Washington High Country ‘With Your Friends The Dogs’

Listen

On my way to meet Heraclio Delacruz, I actually get lost. A few times.

He’s up a Forest Service road, with little to no cell phone service in the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest in Kittitas County.

I can’t find him, so we actually reschedule once I get back to service and agree to try again the next day.

By a miracle, I find him the following afternoon with his well-worn blue pickup truck and trailer. Five friendly dogs come out to greet me.

Heraclio names them off: Gaviota (Seagull), Shadow, Bush, Oso (Bear) and Monkey. These are his loyal companions, and they help keep coyotes, wolves, and even cougars away when he’s walking around with the flock.

RELATED: Meet The Family Running The Last-Of-Its-Kind Sheepherding Operation In Washington

Heraclio is a sheepherder, in Spanish what’s called a “pastor.” He says this is his 18th year with the Martinez family sheepherding operation in Central Washington.

We walk past pine trees, and he welcomes me into what’s his home for most of the year. It’s a humble trailer, hitched to the pickup. Inside, there’s a local newspaper, long distance phone numbers and family photos on display.

He’s one of eight sheepherders that come from Peru to work with the Martinez family. He’s an H-2A worker, a kind of temporary agricultural employee. While most with H-2A status stay for a few seasons and leave within the year, these sheepherders stay for almost three years. Usually they leave with three months to spare, return home to Peru where they stay with family and friends, and then they come back and start the journey over.

Because there’s so many sheep to move, herders have a few tricks to keep count. One method is to count the number of black sheep. Because there aren’t as many black sheep, herders know they might be missing part of their flock if there are fewer black sheep when they do their counts at the end of the day. Another method is to put bells on a few sheep or even mark their wool by painting numbers on them. CREDIT: ESMY JIMENEZ

Heraclio first came to the states when he was in his 30s, and with no prior sheepherding experience. Nearly two decades later, he’s keenly familiar with his flock, the dogs and the forest around him.

Heraclio moves anywhere from 1,000 to 2,000 sheep through grazing parcels in the forest. No fancy technology, no maps, just walking on foot with the help of the dogs.

“They go into the mountain and you can’t see them anymore,” he says in Spanish. “You have to orient yourself by listening to their braying ‘bah bah’ and that’s how you know where the sheep are.”

The day I speak with him, he’s actually searching for stray sheep near the town of Liberty, Wash. He’s down a dozen or so sheep and found five that morning, along a ravine.

Mark Martinez helped him round them up. Martinez is a third-generation sheepherder based in the Yakima Valley, and also Heraclio’s boss.

His is the last sheepherding operation that still grazes on federal land in Washington. He’s also the first to admit how important herders like Heraclio are.

“The H2A process is a lengthy, cumbersome process,” Martinez says. “But in the end it’s a true asset. Without it, we’d be up the creek without a paddle.”

PHOTO ESSAY: The Martinez Family Gets The Sheep From High County To Low Pastures

Martinez brings herders like Heraclio, food, water and supplies every couple weeks. But for the most part the life of a sheepherder is incredibly solitary.

“There’s no one to talk to, you’re alone, with your friends the dogs, the braying sheep,” Heraclio admits.

He’s noted that younger, 20-year olds have tried the job, but always quit. They leave and work construction or find other jobs. He has extended family that now works in California, Utah and New York. But not in sheepherding.

“If it’s hard for the older folks, then it’s even harder for the youth. They’re used to the city. They think ‘I’d better leave’ and they flee. Me? I’m already used to it.”

At nearly 60, Heraclio says he’ll come back for another round of sheepherding if the boss asks him. If not, he says it might be time for him to go back to South America, and hang up his hat — one faded by decades of summer sun and ringed with sweat.

Back in Peru, he’ll trade the solitude of Washington’s forested high country for a home with a family of six, and the bustling city of Huancayo.

Related Stories:

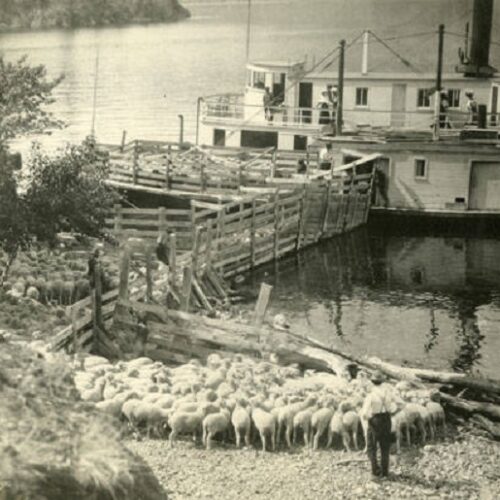

Past As Prologue: Sheep, Ranching And The Beginning Of Industrial Agriculture In The Northwest

Learn how sheep ranchers in the late-nineteenth century in Eastern Oregon were already a part of complex agricultural and industrial systems that provided food, clothing and commodities to markets across the U.S.

Meet The Flockers: Ups And Downs Of A Washington Sheepherding Legacy

In late September, the Martinez brothers moved about half of those 800 sheep from the mountainous terrain around Lake Wenatchee to the irrigated, emerald pastures of Connell, in Central Washington. They did it with the help of some highly skilled men: Peruvian “pastores” or sheepherders. All the way from South America, most of them have been with the Martinez family for decades.

PHOTOS: Follow A Last-Of-Its-Kind Sheepherding Operation In Washington

A flock of 800 sheep calmly sleeps in the chilly September morning. They’re surrounded by stately firs and pines of the Okanogan-Wenatchee National Forest. Mist hangs low on the mountains, creating a scene that feels like it’s from another time. And that’s because it is.