Rare Corpse Flower To Release Its Foul Stench At WSU Vancouver

READ ON

With the name corpse flower, this rare, tropical plant set to bloom at Washington State University Vancouver has quite the reputation to live up to.

“People describe the smell as a mix of rotten fish and dirty socks,” said Steve Sylvester, associate professor of molecular biosciences at the Salmon Creek, Washington, campus.

The native plant from Sumatra is also known by its scientific name, Amorphophallus titanium, but around these parts, the plant is fondly called Titan VanCoug.

“This is my baby,” Sylvester said, proudly adding that it grew two more inches overnight.

Sylvester raised Titan VanCoug from a small seed he planted 18 years ago. It started as a desk plant, but quickly outgrew the office. Sylvester eventually moved the plant to the main floor of the building.

“It was the only place on campus where the ceiling was tall enough,” he said.

Now, Titan VanCoug sits outside under a canopy as Sylvester and the rest of the campus wait for its green leaves to turn dark purple and unfurl, revealing its signature scent.

“We had to move it out of the building,” he said. “It’ll stink too much.”

At age 18, Titan is a bit of a late bloomer. Most corpse flowers bloom for the first time within 10 or 11 years. Sylvester said the plant was set to bloom several years ago, but some overzealous watering split the plant’s bulb into four and reset the entire growth process.

The flower is stinky with a purpose. Scientists say the smell and the dark red color are meant to resemble fresh meat to draw flies inside to help pollinate the flower.

Sylvester has been monitoring the plant closely and says once the color begins to darken, a four-day window will open for the bloom.

“I wake up in the night and worry about it,” he said. “But I’m really excited. I will be here with it for as much time as I can tolerate.”

Sylvester expects the corpse flower to bloom in the coming weeks. Then, visitors will have a brief 24 to 48-hour window to catch a whiff.

Visitors can see — and smell — Titan VanCoug outside Washington State University Vancouver’s Science and Engineering building, or simply watch the plant live via webcam and spare their noses.

Copyright 2019 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

New funding to build farmworker housing in the Pacific Northwest, nationwide

The United States Department of Agriculture is soliciting applications for funding to build farmworker housing nationwide.

In the Pacific Northwest, leaders hope the money can address gaps in farmworker housing. The Pacific Northwest is in a housing crisis and that impacts rural small businesses and agricultural producers, as well as farmworkers, said Helen Price Johnson, who is the Washington State Rural Development director for the USDA.

Continue Reading New funding to build farmworker housing in the Pacific Northwest, nationwide

The North Pole isn’t the only place for Santa to find reindeer – they’re in Goldendale, too

Tanya Clarke and Daniel Connell own and operate Goldendale Reindeer Farm, which has nine reindeer. (Credit: Courtney Flatt, Northwest News Network) Listen (Runtime 1:27) Read The reindeer at Goldendale ReindeerFarm… Continue Reading The North Pole isn’t the only place for Santa to find reindeer – they’re in Goldendale, too

The cow that stole Christmas: Nearly 20 years since mad cow disease was first discovered in Washington state, one family still struggles

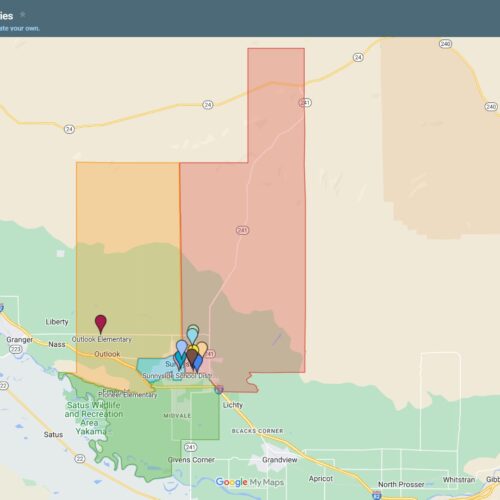

Sergio Madrigal and his wife, Rosa, stand outside the farm they owned, until recently, near Sunnyside, Washington. (Courtesy: Anna King / Northwest News Network) Listen (Runtime 2:56) Read It has… Continue Reading The cow that stole Christmas: Nearly 20 years since mad cow disease was first discovered in Washington state, one family still struggles