As Okanogan River Recedes, Memories Of Past Floods Remain

BY EMILY SCHWING & ESMY JIMENEZ

The Okanogan River has receded from its emergency flood stage seen for several weeks in May. Left behind are the memories and high-water marks of floods and natural disasters past.

For many locals, floods are another part of life in a county that also deals with drought and wildfires.

The county made national headlines in 2014 with the Carlton Complex fire and again in 2015 with the Okanogan Complex. That was the largest wildfire in recorded Washington history. The same year, Governor Inslee declared the entire state under drought conditions.

Previous Floods

Though fire and smoke-filled summers are more common in the Okanogan Valley, flooding isn’t a new reality in north-central Washington. There have been two major floods in previous decades.

Memories of those floods along the Okanogan River are burned into the collective memory of this valley.

Arnie Marchand is from the Okanogan Tribe and is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. He was born in Omak. Marchand was only 3 years old when the second-worst flood in recorded history took place back in 1948. He doesn’t remember it, but he remembers his family’s stories.

“You have to understand that in ‘48, the war just got over, people are just coming back, the economy is picking up,” Marchand said. “It’s really moving rapidly,” he said.

The flood slowed some of that progress, but luckily Marchand’s parents still had work.

Arnie Marchand now works at the museum and visitor’s center in Oroville, Washington. He was born in Omak in 1945. CREDIT: EMILY SCHWING/N3

“It didn’t hurt the agriculture that much,” he said. “It hurt a couple of orchards, but mostly dad and mom were like every other Indian in this valley. You couldn’t serve white people in a restaurant, all you had was the orchard work or construction work, that’s all you could do. So, if it didn’t drown the orchards, it didn’t hurt your job.”

1948: ‘‘It Caught Everybody Off Guard”

“Gosh, it just flooded everything and it was so exciting,” said Ruth Tembey. She was in middle school in 1948 when the Okanogan River flooded at Tonasket.

“It caught everybody off guard because there hadn’t been a flood recorded, I don’t think,” she said. She turned to her husband Richard, who was also in middle school in Tonasket at the time.

“Well, there was one, like, in 1898, or something like that,” he recalled. “That was supposed to be way up to some pine tree that was a quarter mile back from the river,” he said.

That flood actually took place in 1894, but there are no official records because the National Weather Service didn’t start collecting river data for the Okanogan until 1929.

It would be another 24 years before the valley saw a flood that was even worse than in 1948.

“In ’72, the kids took rowboats out and rowed through the neighbor’s house,” Ruth Tembey recalled with a laugh. “I think they could get through the window and just rowed through.”

Marchand said the flooding in 1972 was very serious.

“There’s lots of things that were lost in ’72,” he said. “Thank God the devastation (this year) isn’t that bad yet.”

Colville Tribal member Don Abrahamson remembers dealing with the aftermath 1972 flood when he was 14.

“I just had to come back and clean up mud, there was mud everywhere,” he said.

In May, Abrahamson and his family of five were under a level 3 flood evacuation notice during this year’s flood. Their backyard in Omak was partially underwater.

His wife Sabrina said the hardest part was waiting through the uncertainty.

“They’ll tell you it’s gonna flood to 21 (feet), then to 19. You’re on a rollercoaster,” she said. “You’re thinking ‘I’m fine.’ Then you get another report that says ‘No you’re not.’ It’s the not knowing that’s the frustrating part about it.”

“It’s just a part of nature,” Don Abrahamson said at the time. “You got no control over nothing so you gotta do whatever you can to protect yourself.”

While they waited, they sat on their back porch watching otter, beaver and carp in their backyard.

In The Archives

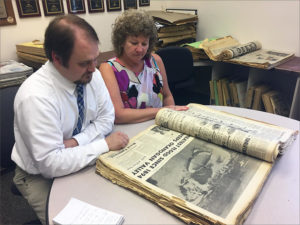

The floods of 1972 and 1948 were so significant that when Brock Hires saw forecasts for major flooding again this year, he paid a visit to the archives of the Omak-Okanogan Chronicle. Hires is the newspaper’s managing editor.

In an enormous book labeled ‘Archive 1972,’ photos from the time show the Stampede Arena in Omak filled with water and homes and business flooded throughout the valley.

Brock Hires, managing editor of the Omak-Okanogan Chronicle, and Teresa Myers, the paper’s publisher, look through photos and stories of flooding in 1972 in the newspaper’s archives. CREDIT: EMILY SCHWING/N3

“In every picture, there are people moving and bustling to help each other out,” Hires said. “It destroyed homes, it flooded fields and [it was a] $20 million-dollar loss. And the flood of ’48 brought $6.8 million worth of loss. Now, with inflation, that comes out to about $70 million today.”

The communities along the Okanogan River learned something from these previous floods. U.S. Highway 97—the main highway that runs north-south through the valley—was elevated and strengthened during the Cold War.

After 1972, most of the communities also set about constructing dikes.

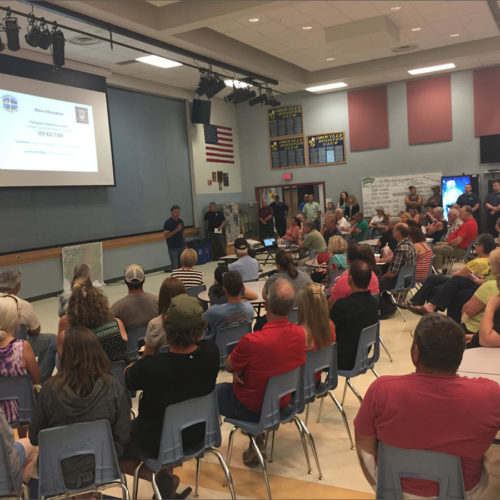

And with modern technology and communications systems, the communities now have days, if not weeks to prepare for floods—which they didn’t decades ago.

Related Stories:

Emergency Managers In ‘Defense Mode’ As Okanogan Flood Outlook Changes To Lower Level

A week ago, forecasters were predicting the Okanogan River might crest this weekend near a record flood mark set back in 1972. Now, emergency managers are moving into “defense mode” and are now predicting somewhat lower water levels.

Okanogan And Ferry County Flooding: Emergency Information And Updates

Conditions in Okanogan and Ferry counties have moved to a major flood state, where Governor Jay Inslee has declared an emergency. The Okanogan River is expected to continue rising through the weekend and through the following week to a level not reached since the historic flood of 1972.

Despite Floods, Officials Say Municipal Drinking Water In Okanogan Valley Still Safe

Emergency management officials are trying to protect drinking water systems throughout the Okanogan Valley from flood water contamination.