Pulse Of The Palouse: Trade Wars Hitting Northwest Farmers Who Grow Chickpeas, Lentils And Peas

Listen

This story starts at the bin.

Icy, fat raindrops zing off the metal roof and bounce down the corrugated sides.

Farmer Allen Druffel stands outside the silo shuffling his feet in the gravel. This co-op bin is where he stores his dried garbanzo beans in the tiny berg of Colton, in far-eastern Washington.

“I’m not sure what to say,” he laughs a bit. “[It’s] a big silver bin of beans.”

This place should be busy. Trucks should be loading, hauling this year’s crop to markets and international ports. But mid-afternoon, there’s just the rain.

Since farmers like Druffel brought in this year’s crops — hardly any garbs, as farmers call the legume also known as chickpeas, have moved.

“Thirty to 40 percent of our total revenue is in the bin,” Druffel says. “And we’re not sure what we want to do with it.”

Bitter Bumper

Druffel saw the market drop only when it was too late — after he had already planted the crop in the spring, and then again after harvest.

“It was a bit of a rollercoaster,” he says. “It was one of the best crops we’ve ever harvested. And then to see the pricing take a 40 to 60 percent fall is really unfortunate. If you’re talking real numbers, in February of 2018 I sold chickpeas for 50 cents a pound – and today they’re trading at 18 cents a pound.”

Snow-covered farm fields roll out outside of Kendrick, Idaho. Farmers are stumped on what to plant this coming spring, as many of their traditional dryland crops are priced below the cost of production right now. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

And it’s bad times for the other crops too, lentils and peas. In the ag industry, they’re all called “pulse crops.”

So what happened?

Bean Counter

Dirk Hammond is an honest-to-goodness bean counter. He does the accounting at George F. Brocke & Sons, a pulse crop exporter in Kendrick, Idaho.

“I tell people this year, I feel like I’m the Grinch because of, because of the prices,” Hammond says. “And it’s, you know, nothing that we as a company, or any grower or landlord has done — it’s just a circumstance of global politics and global trade.”

At Brocke, hightech systems sift through the harvest, sorting out the chaff and debris and packaging the pulse crops for shipment around the world. In the deafening facility, robots whizz and whirl stacking hefty bags of garbanzo beans on wooden pallets.

Hammond says this year’s pulse crops were nearly bustin’ out of the bins. Farmers had plenty of moisture for their dryland or non-irrigated crops. So, they had really great quality and yields. And across the nation, farmers planted more garbs than ever before — increasing the acres grown from 600,000 acres to 800,000.

Chickpeas, wheat and peas make up a large percentage of the crops that are grown in this dryland area of the country called the Palouse. At cooperative silos like this one, the grain is sampled to make sure it meets strict quality standards. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

The real trouble started in early 2017, with the U.S. pulling out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Late in 2017, India imposed a global tariff on pulse crops and other farm products to protect its own growers.

Then, came President Donald Trump’s steel and aluminum tariffs.

China and India are the two largest buyers of American garbanzos, peas and lentils. Those exports have all but stopped.

Because China and India put big tariffs on American pulse crops. And other countries are holding off on buying them too while the prices are unstable.

‘Real Catastrophe’

Down the road, in Moscow, Idaho, Tim McGreevy is the head of the American Pulse Association. He represents pulse crop growers across the nation.

In the near 25 years he’s held the job, McGreevy says he’s never seen such a tough market. He estimates his pulse growers have lost $500 million so far.

“To describe this as a bad year for export markets is a gross understatement — this has been a real catastrophe,” McGreevy says.

And if markets don’t reopen, real soon it is going to get a lot worse for farmers and processors.

Phil Hinrichs stands near 2,500 pound export totes of garbanzo beans that his factory cleans and fills. These large containers will be loaded onto trucks and shipped around the world. The problem for Hinrichs is, not much of anything is shipping right now with trade tariffs in place against U.S. commodities. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

So far, pulse farmers haven’t been awarded much in the way of government payments, or help.

There are federal loans – and some farmers will have to take them to keep operating as they hold onto their crops, hoping for better prices by spring.

And in January and February it’s the bankers who will largely decide farmers’ fates. Most farms have to borrow operating cash for each coming year to buy things like fuel, seeds and chemical fertilizer.

Right now, it’s a question of what to plant to make those costs back.

There isn’t much in dryland that’s making money right now. Prices are at or below cost of production in this area for wheat, barley, rapeseed, lentils, garbs and peas.

“There’s not a lot to run right now, that is the absolute truth,” McGreevy says.

Hits Home

The shakeout could happen by spring.

McGreevy says in this hard time, it’s the older farmers who might decide to just quit before the next go round. But it’s the young farmers who might be giving up the keys to the farm if things don’t turn around in a matter of months.

Dry garbanzo beans spill between Phil Hinrichs’ fingers. Hinrichs Trading Co. readys chickpeas for hundreds of products on domestic store shelves and exports the commodity in bulk across the globe. CREDIT: ANNA KING/N3

“Young farmers generally have a lot more debt that they are assuming as they are just starting off in their careers,” he says. “If they are purchasing any property, with prices that we are seeing right now, it’s very difficult to cash flow that.”

On farmer Allen Druffel’s remote spread, the dirty-white sky is indistinguishable from the earth. Just a 5 o’clock shadow of wheat stubble bristles out of the snow, keeping one grounded. Druffel tries to brush off this year’s disappointment and his family’s risk.

“No, it doesn’t bother me,” Druffel says in a low voice. “It’s the game we chose to play. I do it ‘cause I love it.”

Pressed a bit more, Druffel smiles. Through welling tears, he reluctantly admits:

“Oh, it hits home.”

CORRECTION: In the audio, as in a previous web version of this story, we incorrectly say that the U.S. pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2018. The correct year is 2017. Also, the web version has been updated to say that India imposed a global tariff on pulse crops and other farm products in late 2017.

Related Stories:

Dairy Steamer: Milk cows, like people, get hot and farmers use innovative ways to cool them

Maple, the 7-year-old yellow lab, takes a swift lick on a couple of milkers near Sunnyside, Washington. (Photo: Anna King) Listen (Runtime 3:54) Read It’s hot! It hit about 110

Berry Bake: Northwest Blueberry, Raspberry, Blackberry Crops Might Be Roasted From The Heat Wave

Blueberries, raspberries and blackberries from Oregon to Washington to British Columbia are baked on the bush and vine. Growers are calling the heat damage widespread and catastrophic.

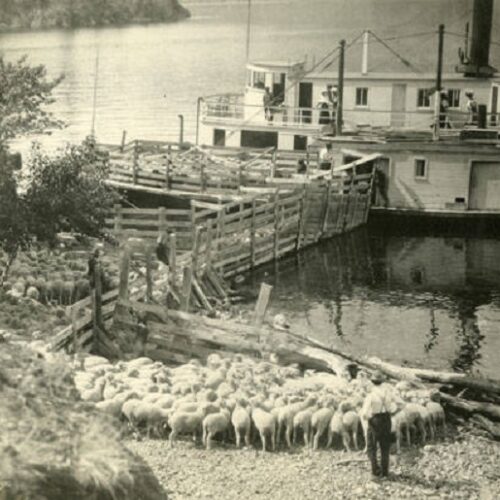

Past As Prologue: Sheep, Ranching And The Beginning Of Industrial Agriculture In The Northwest

Learn how sheep ranchers in the late-nineteenth century in Eastern Oregon were already a part of complex agricultural and industrial systems that provided food, clothing and commodities to markets across the U.S.