‘We Need Action.’ Yakama Nation Leads Discussion On Violence Against Women

Listen

On Monday, Jan. 14, the Yakama Nation held an all-day community meeting in Toppenish, Washington, to discuss violence that affects Native American women and girls.

Over 200 people attended the community meeting, including Yakama tribal members, the Washington State Patrol, local police departments, and the Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs.

This comes after a new state law last year that tasked the state patrol with identifying problems and solutions in reporting and investigating cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW).

Community members talked about barriers to reporting these crimes, like proper training for police officers. One woman, whose name we’re not including for privacy reasons, opened up about the experience, saying to the crowd:

“A relative tried to report a sexual assault and an officer that responded had seen her earlier in the day and he asked her ‘Why didn’t you say something earlier?’ and that’s not something to say. That same relative was actually assaulted on three different occasions within a couple of months. On another occasion, the officer said that it wasn’t rape, it was consensual.”

Other barriers include systemic oppression that Native women face at the intersection of racism and sexism.

Jurisdiction is another challenge. Crimes are bounced between tribal police, local law enforcement, and the FBI, depending on whether the victim and perpetrator are Native or non-Native, and where the crime took place.

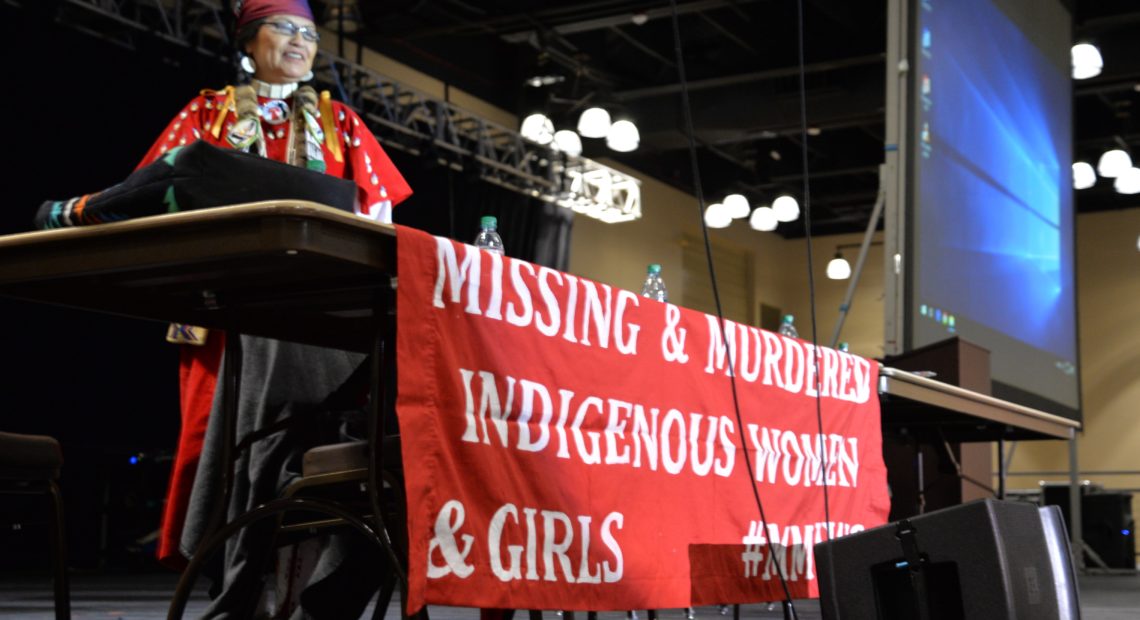

Over 200 people attended the community meeting including Yakama tribal members, the Washington State Patrol, local police departments, and the Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs. According to research by the Urban Indian Health Institute, Washington state had the second highest number of MMIW cases in the U.S. CREDIT: Esmy Jimenez/NWPB

The city of Wapato Police Department stressed during the meeting that local law enforcement was and has been committed to supporting the Yakama Nation. In the past, a Yakama tribal officer rode with Wapato police. Both officers and community members offered it as a possible initiative to reinstate.

Other Yakama members asked police officers to get to know the culture of the tribe, to educate themselves on celebrations and religious practices in order to build trust and genuine connections with the community.

But for some tribal members, these initiatives — while helpful — are not enough.

Charlene Tillequots, a Yakama member of the MMIW special committee, pushed back on more talking.

“We don’t need another study,” Tillequots said. “We need action to address a human rights issue.”

Tillequots and other women said they already knew the scope of the problem; they’ve been enduring it for years. When victims were able to come forward and report a problem, officers took hours to respond to complaints, especially if victims were in rural parts of the reservation like White Swan. The response caused Yakama members to lose faith in the justice system, meaning crimes or missing persons would go unreported.

Research by the Urban Indian Health Institute found 5,712 Native women were missing or murdered in 2016, but only 116 of those cases were logged in the U.S. Department of Justice’s database. Washington state had the second highest number of MMIW cases.

Roxanne White, a leader in the MMIW movement and sexual assault survivor, asked people at the event to stand if they or someone they loved had experienced violence, gone missing, or been murdered. About a third of the room stood up.

“This is why we’re here,” White said crying. “Many people have come here today because they’ve been waiting for this time. For us to get together, to be heard, and to feel protected.”

To bring more attention to this issue, the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s committee is expected to lead the Women’s March in Yakima, Tri-Cities and Seattle this weekend. The group led the 2018 march in Seattle.

Copyright 2019 Northwest Public Broadcasting

Related Stories:

Cantwell dice que Washington necesita más recursos para enfrentar crisis de MMIP

En una conferencia de prensa realizada en el Seattle Indian Health Board, dirigentes tribales, familiares de personas desaparecidas y la senadora estadounidense Maria Cantwell (D-Washington) afirmaron que se necesitan más recursos federales para abordar la crisis de las personas indígenas desaparecidas y asesinadas en el estado de Washington. La conferencia tuvo lugar el 5 de mayo, Día Nacional de Concientización sobre Personas Indígenas Desaparecidas o Asesinadas (MMIP).

Cantwell says Washington needs more resources to address MMIP crisis

Tribal leaders, family members, and Democrat U.S. Senator Maria Cantwell from Washington asked President Biden for more federal resources to address the missing and murdered indigenous women and people crisis in Washington.

MMIWP: Comunidades indígenas siguen alzando sus voces en la búsqueda de sus seres queridos

Al comenzar el mes nacional de concientización sobre los casos de mujeres y personas indígenas desaparecidas y asesinadas (MMIW/P), las familias siguen llamando la atención sobre las barreras y los retos que experimentan al abordar la crisis en Washington.